A Political Earthquake

The person who lost the most from Netanyahu’s coalition upheaval is Yitzchok Herzog. Like the man in the parable who ate the rotten fish and was expelled from the city, Herzog has emerged as a person who has made every mistake possible. His own party is already calling on him to step down as the party leader, and he also can no longer portray himself as a stalwart opponent to Netanyahu. After all, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the prime minister until last Wednesday, and he was on the verge of becoming Netanyahu’s most senior partner in the government.

Regardless of whether Herzog remains in charge of the Zionist Camp party, a debate has already begun raging as to who will be the head of the opposition. That is a position that gives its bearer power, privilege and importance. The opposition leader speaks after the prime minister in every debate. By law, he must be invited to monthly meetings with the president and prime minister. He is also visited by any foreign dignitaries who wish to cultivate the appearance of being balanced. Even Ayman Oudeh, the leader of the Arab list, is interested in the post. As is Yair Lapid.

Herzog has become a laughingstock not only in his own party, but in the entire Israeli political world. The Likud party believes that they have decimated the Zionist Camp and that it will no longer be a political rival to them in the next elections. On that note, there are rumors – which admittedly lack a substantial basis – that the agreement between Netanyahu and Lieberman includes a stipulation that Lieberman will support Netanyahu for prime minister in the next elections, and that he will side with Netanyahu in any conflict between the prime minister and Naftali Bennett. This is further evidence of the widespread belief that Netanyahu is interested in nothing more than his own political survival. But in terms of his political machinations, Netanyahu is the most sophisticated prime minister the State of Israel has ever had.

In short, this past week has been both bewildering and astounding. We have essentially been through a political earthquake. This is how the summer session of the Knesset has begun. Let us daven that we will all get through the summer in peace.

The Judge’s Pilpul

As you are aware, Aryeh Deri has been the subject of a police investigation focused on certain real estate dealings that took place during his exile from politics. Deri is confident that the situation will end well, and we are davening for him. Meanwhile, he has received an encouraging sign from the Supreme Court, as a majority ruling rejected an appeal for Deri to be dismissed from his position as Minister of the Interior. When Deri first became a minister in the government, the court rejected a similar appeal to bar him from holding any ministerial position at all. Once he became the Minister of the Interior, another appeal was filed for the court to prohibit him from holding that position, even if he could head a different ministry. This past week, the court rejected that appeal as well.

The court’s ruling was based on a majority of two against one. Justice Salim Jubran (a Muslim Arab) and Justice Yoram Danziger (a chiloni Jew) ruled that Deri is a “kosher” Interior Minister, while Justice Neal Handel, a religious Jew, accepted the appeal and ruled that the prime minister should dismiss him. Handel was one of the justices who rejected the earlier appeal against Deri serving as a minister altogether, meaning that in his view, Aryeh Deri may be a minister, but not the Minister of the Interior.

Handel’s reasoning is explained in a decision covering 33 pages, much more than the 22 pages used by Jubran for his arguments. Part of Handel’s argument is that Deri’s appointment lacks “reasonableness,” and on that point, I have no wish to enter into a debate with him. That is simply his opinion. But six pages out of the 33 deal with “Jewish law,” and on that aspect of his judicial opinion, he has left himself open to critique. Let us say simply that if he were to submit his judicial opinion in a bid to be accepted to a kollel for outstanding yungeleit, he would certainly be rejected.

In these arguments, Handel cites evidence that proves nothing, relies on specious arguments, quotes only portions of the relevant texts, and draws conclusions that are utterly detached from the sources on which he claims they are based. His thesis is simple: The main point is that complete teshuvah, in which a person’s sins are washed away and can be considered as if they never happened, is possible only in the realm of relations between man and his Creator. In the realm of interpersonal relations, though, no sin is ever totally wiped away. Handel draws a contrast, in his words, between “religious repentance” and “social repentance.” He claims that a sinner can never be permitted to return to his position of power, and certainly not after a brief interlude. He seeks to prove this by citing the case of Moshe and Aharon, who were punished at Mei Merivah by being barred from leading the Jewish people into Eretz Yisroel. But Handel forgets that Moshe Rabbeinu did not enter the land even as an individual, even though that would not have been a manifestation of leadership.

Handel also quotes a line from the Rambam: “A rosh yeshiva who sins is given lashes in the presence of three people and may not return to his position.” In the Rambam itself, this sentence begins with the word “but,” which Handel omits for a reason: In the previous line, the Rambam states, “A kohein gadol who sins is given lashes in the presence of three people, like any other person, and returns to his position of greatness.” Furthermore, in the preceding paragraph, the Rambam rules that any person who sins and is given lashes is permitted to return to any position he held prior to his offense. Handel is guilty of quoting the passage only partially, and in a way that causes important information to be concealed. More than anything else, though, the question is: What led Handel to conclude that Deri is more analogous to a rosh yeshiva than to a kohein gadol or any other person?

Another point: It is very unclear why Handel believes that Deri should be permitted to hold the post of Minister of the Economy, but not to serve as Interior Minister. Moreover, Handel admits that if more time had passed, he, too, would have rejected the appeal against Deri. Well, how much time did he have in mind? Five years? Thirty years?

Handel’s opinion relies heavily on a book by Professor Nachum Rakover on the subject of the attitude of the law toward a convict who has served his sentence. I believe it is possible that Handel simply copied many of Rakover’s sources for his own decision without bothering to examine the sources themselves. I spoke to Rakover at length on the subject and presented my objections, some of which he accepted. But Rakover advised me not to be too quick to argue with Handel, whom he termed a “talmid chochom” and “no simpleton.” One thing, though, was clear: Professor Nachum Rakover himself does not have a position of his own on the subject of Aryeh Deri. He was surprised to hear from me that Handel authored the minority opinion that Deri should be disqualified from serving as Minister of the Interior.

Damaged Mezuzos for the Army

This week, I was present when the directors of the Genizah Klalit – the organization responsible for the blue shaimos bins that can be found on the streets of Israel – met with Oded Palus, the director-general of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and his staff. The meeting taught me a good deal about the dedication of these activists, who have taken it upon themselves to preserve the country’s shaimos and protect it from disgrace. Without their work, in the best case scenario, countless pages invested with sanctity would be littering the country’s streets. They are people who embody the ideals of acting lesheim Shomayim and without any interest in personal gain. One of them, Rav Eliezer Bodenheim, is someone I know personally.

I also learned about the positive developments that have been unfolding in the Ministry of Religious Affairs under the aegis of its quiet, unassuming minister, Dovid Azulai. For many years, Oded Palus has been advancing initiatives, quietly but surely, that benefit both the general chiloni populace and the chareidi sector. For instance, did you know that the entire process of registering for marriage has become computerized? This has eliminated the requirement for the names of couples registering for marriage to be publicized in the newspapers. Did you know that a government committee is working to secure equal status for the country’s botei din with its secular courts? In addition to that, Palus has been working to find new ways to help the genizah klalit deal with shaimos, and with the lack of public awareness of the issues involved.

A particularly disturbing story regarding the misuse of shaimos recently came to my attention: Throughout the country, one can find small bins designated for the disposal of aged or damaged mezuzos. Recently, there has been a rash of episodes in which these bins were broken into and their contents stolen, which led to a police investigation. The investigation revealed that some unscrupulous individuals have been taking the mezuzos and selling them to the IDF. The army is currently relocating from its headquarters in the Negev, and the move has created a need for hundreds of mezuzos. Apparently, someone decided to take advantage of the situation – even though it meant causing the army and its soldiers to be unwittingly remiss in fulfilling their halachic obligations.

This is a revelation that is both shocking and deeply disturbing. One would expect the army to do its homework before making any purchase, and if this is how its acquisitions are managed, then we are in a sorry state indeed.

At the same time, if the army’s carelessness extends only to the mezuzos it purchases, then the situation is infinitely worse.

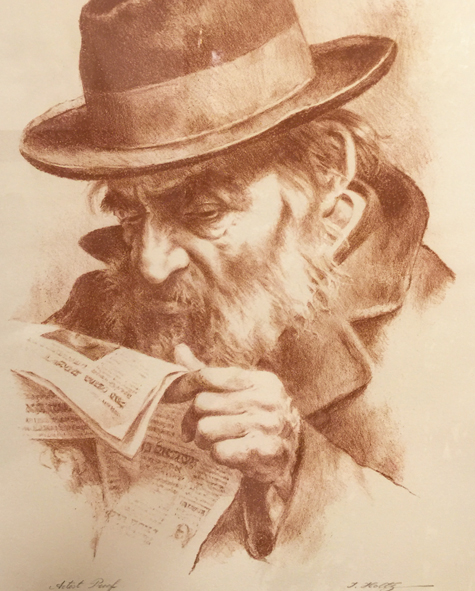

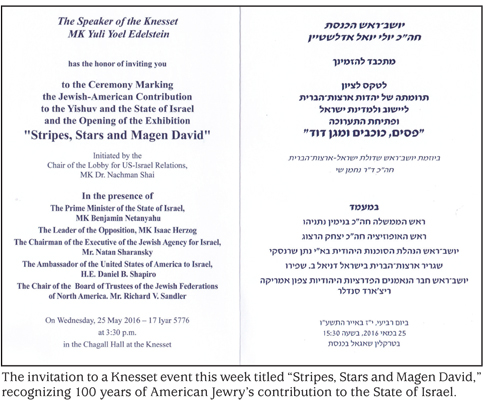

Stripes, Stars, and the Magen Dovid

This week, we will receive a visit from a delegation of Reform Jews from America. Is their goal to help the Israeli Reform movement in its efforts to violate the sanctity of the Kosel Hamaarovi? Perhaps. The official purpose of their visit, though, is to mark a special day in Israel dedicated – and I quote – to “acknowledging the contribution of the Jews of the United States to the settlement and the State of Israel.” As I write these words, I am holding an elegant invitation to a gathering in honor of the occasion, which is scheduled to take place in the Chagall Hall of the Knesset. According to the invitation, there will be an exhibition titled “Stripes, Stars, and the Magen Dovid.”

The speakers at the event will be Binyomin Netanyahu, Yitzchok Herzog (if he is still the chairman of the opposition), Natan Sharansky, Ambassador Dan Shapiro, and Mr. Richard Sandler, chairman of the board of trustees of Jewish Federations of North America.

On the same day, the Knesset Education Committee will hold a discussion on the subject of “the contributions of American Jewry to the educational institutions and community centers of Israel, marking 100 years of the involvement of United States Jewry in the Jewish settlement and the State of Israel.” The list of invited participants includes representatives of the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of the Economy, the Ministry of Diaspora Affairs, the Union of Local Authorities in Israel, the Israel Union of Education Directors in Local Municipalities, the Jewish Agency, the Joint, and the Hadassah Women’s Organization, and members of various research institutes, philanthropic funds, school networks, teachers’ organizations, parents’ organizations, and youth and student councils. My question is: Can anyone explain to me what this centennial is about? What was it that began 100 years ago? Perhaps I will be wiser on that subject next week after I have heard the speakers. I will let you know…

Why Check If Someone Is Jewish?

I recently noticed a function being held at Sprinzak Hall in the Knesset building. I took a peek inside and found that the dais was occupied by MK Aliza Lavie of Yesh Atid, who is known for her efforts to promote religious “compromises”; David Stav, rabbi of the city of Shoham and head of the Tzohar rabbinical organization, which is known for its own all-too-accommodating attitude on religious matters; and Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, rabbi of the town of Efrat. Lavie was speaking, and I was able to infer that the event was dedicated to discussing how to advance proposals concerning religious affairs that have been blocked by the government. At that point, I left. I could only imagine what sort of ideas are racing around in these people’s minds. About an hour later, I met Rabbi Riskin in an elevator. I remembered him from an event in America that we had both attended years earlier.

I decided to pose a question to the rabbi of Efrat. “Why are you with Mrs. Lavie and not with us?” I asked.

He smiled, as he always does. “Who is ‘us’?” he asked, as if he didn’t know.

I tried rephrasing my point. “You are closer to us than to her!” I exclaimed.

Once again, he smiled. “Of course,” he said.

Speaking of Aliza Lavie: Not long ago, she submitted a parliamentary query that was answered by the Minister of Religious Affairs. When I read her question, I was shocked. “The agency of the rabbinic courts that deals with confirming Jewishness has a practice of opening investigative files into the personal status of citizens who did not seek the bais din’s services at all,” she wrote, “using information that they receive through all sorts of channels and from all sorts of people. Sir, I wish to ask you: What will you do to stop this practice and this ongoing invasion of privacy? Sir, just this week I received two more complaints on this subject. Thank you.”

The minister replied that the bais din has the authority to conduct these investigations, which it does only when there is a practical purpose, either to permit an agunah to remarry or to prevent a non-kosher marriage. Lavie listened to his response and was not satisfied. “We are living in a very special generation, a time of redemption, when our people are being gathered in from all over the earth,” she said. “There are many people who have come here who, for some arcane halachic reason or another, do not meet all the specifications. I still do not understand what authority the court possesses to summon a person without any request being made at all. And why is there such a thing as investigating a person’s Jewishness at all?”

Can you believe it? In effect, she is asking why it is necessary to investigate whether a person is Jewish, when no one has even asked. The fact that some of these “Jews” may in fact be gentiles, and that they may be intermarrying and breaching the boundaries of halachah, doesn’t seem to bother her at all.

On Mutual Respect

In conclusion, here are some thoughts relevant to this time of year, and to the imperative of treating others respectfully. As we all know, the talmidim of Rebbi Akiva perished because they failed to demonstrate proper respect to each other.

There is a commonly asked question regarding the mitzvah of v’ahavta lereiacha kamocha: How can the Torah enjoin us to love others as much as we love ourselves? This seems to be beyond the capabilities of the average human being. I once heard a talmid chochom answer this question by positing that the word “kamocha” does not define the scope of the obligation. Rather, it is meant to advise us on how to fulfill the mitzvah. If you want to love others, the Torah teaches us, then treat them “kamocha,” as if they were you. Is there any person in the world who would fail to find some way to defend himself against an accusation? Is there any sin for which a person couldn’t find room in his heart to forgive himself? Of course, the answer is no, and the Torah therefore teaches us that in order to love others, we must value their honor and dignity as much as we value our own, and we must judge them as we would judge ourselves.

Rav Nesanel Elbaz, a rov in the Givat Shaul neighborhood of Yerushalayim, once wrote a letter to Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach with a halachic shailah. Along with his own missive, he enclosed a stamped envelope bearing his address: “Nesanel Elbaz, Rechov Kotler 7, Yerushalayim.” When the envelope arrived in the mail, he discovered that Rav Shlomo Zalman had made two corrections: The title “Rav” had been added to Rav Elbaz’s name, and the name of the street had likewise been altered to “Rechov Harav Kotler.”

The Klausenberger Rebbe once related: “I remember that when I was in the city of Bogota, the capital of Colombia, over twenty years ago for the founding of the Satmar community there, I was approached by a person who I later learned was far removed from Torah and mitzvos. He said to me, ‘Rebbe, I was in Eretz Yisroel recently and I saw many people driving their cars on Shabbos along the coast in Tel Aviv and publicly desecrating the Shabbos.’ I asked him how much time he had spent in Eretz Yisroel, and when he told me that he was there for two weeks, I replied, ‘This is incredible! You were there for only two weeks, yet you saw so many people driving on Shabbos, while I have spent much longer periods of time there and I never saw people driving along the shore in Tel Aviv.’ That is the nature of a rasha. He loves to see the negative in other Jews,” the Rebbe concluded.

Concern for others is one of the defining traits of any great man. A person’s interpersonal conduct is a reflection of his bein adam laMakom. I once heard from Rav Shlomo Wolbe that it is impossible for a person to perfect his conduct in the realm of bein adam laMakom yet be lacking in bein adam lachaveiro. On that note, I have heard a number of fascinating stories from Rav Elimelech Biderman about the profound care exerted by great tzaddikim to avoid causing the slightest discomfort to others. Here are three of those true stories:

Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach once related that in his youth, he habitually walked his uncle and rebbi, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, home from his shiur. One day, when they arrived at Rav Isser Zalman’s home, Rav Shach watched as the rosh yeshiva climbed the steps to his home, then immediately turned on his heel and returned to the street. He waited for a short time, then repeated the process, climbing the steps and coming back down again. Rav Shach approached Rav Isser Zalman and questioned him about his behavior, to which Rav Isser Zalman responded,

“There is a widow working in my home right now, and as I arrived at the doorway, I realized that she was singing. If I entered the house, she would have to stop singing and that might cause her distress. Therefore, I am waiting until she finishes her work – and her singing.” Had Rav Isser Zalman entered his own home, he wouldn’t have been guilty of even the slightest violation of the prohibition to oppress a widow; nevertheless, the gedolim of our people have always been exquisitely sensitive to the innermost needs of others for sympathy and support.

In the bais medrash of the Satmar Rebbe zt”l, an imperfection was once discovered in a Sefer Torah in the middle of krias haTorah. The Rebbe began examining the sefer with great care and asked for a variety of seforim to be brought for him to consult. When he had researched the issue thoroughly, he concluded that it was indeed preferable to use a different Sefer Torah. Afterward, someone asked him, “Rebbe, the problem with the Sefer Torah rendered it unquestionably invalid. Why did the Rebbe spend so much time researching the question?”

The Rebbe replied, “Didn’t you see that the sofer who wrote the Sefer Torah was present in the bais medrash? I spent all that time researching the issue so that it would appear that I had disqualified the Sefer only as a chumrah, so that he wouldn’t be embarrassed.”

A man of lukewarm religious devotion once approached the Imrei Chaim of Vizhnitz with his son to celebrate the first time the boy would put on tefillin. After davening, the father placed some food and drink on the table. The chassidim hesitated, realizing that the kashrus of the food was dubious, yet they did not wish to embarrass the visitor. As they struggled to figure out a way out of their quandary, the Imrei Chaim removed his Rashi tefillin, approached the table, and took a small quantity of cake. “I, too, have the minhag not to eat between the tefillin of Rashi and the tefillin of Rabbeinu Tam,” he said, and he proceeded to instruct his gabbai to bring the food home. The chassidim quickly followed their Rebbe’s lead, and the visitor was spared from shame.