Holocaust memoirs record many situations in which a Jew or group of Jews found themselves in unprecedented moral dilemmas that tested every drop of their spiritual fiber. In “Hidden in Thunder: Perspectives on Faith, Halacha and Leadership,” by Prof. Esther Farbstein, first-person accounts bring the reader into the heart of some of these wrenching quandaries.

One of these accounts unfolds in Siennica, a Polish shtetl of about 1000 people, southeast of Warsaw. More than half of the town’s population was Jews. Siennica was occupied by the Germans in 1939, after their lightning conquest of Poland which set the stage for the Nazi slaughter of more than three million Polish Jews.

The story of this shtetl shines a light on how ordinary Jews turned to their rabbonim in those dark days for life-and-death questions that confronted them. Many of these dilemmas pitted self-interest against Torah ethics and obligations.

These simple folk, tormented with fear for themselves and their families, could have allowed self-interest to guide them but they did not choose this easier path.

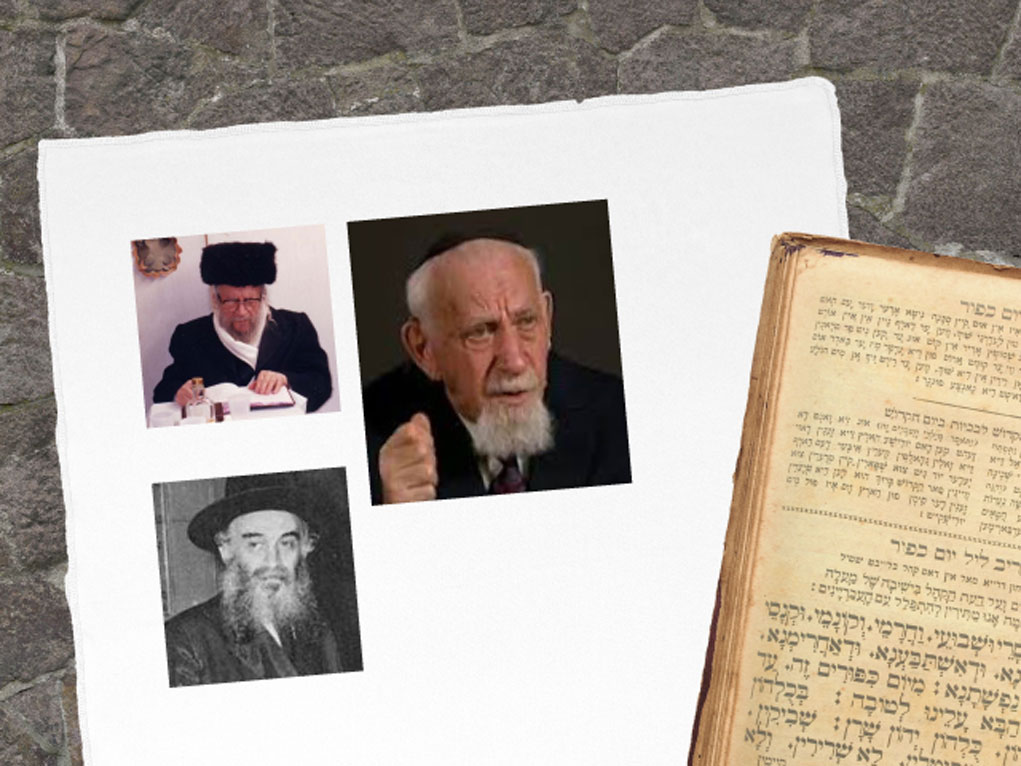

The saga of Siennica is chronicled by two rabbonim who were present at the scene; they were among the very few Polish rabbonim to survive the Holocaust. One was the rov of the town, Rav Eliezer Paltiel Rothblatt, who was appointed rov of Siennica while still in his twenties.

The other was Rav Shaul Dovid Magulies, a talmid of Rav Meir Shapiro of Lublin and the av bais din in the nearby town of Pruszkow, renowned for his phenomenal Torah erudition. He had fled to Siennica with an influx of Jewish refugees from other Nazi-occupied towns. The refugees were hosted in the shul where local townspeople provided them with food and drink.

OUR SOULS WEPT IN SECRET

The agony of Siennica began on erev Rosh Hashanah, 1939, when the Nazis stormed into the town, driving all the residents into the streets and forcing them into the church at the edge of town. Blood ran in the streets as the Aktion was brutally carried out.

As the church was jammed with Jews and Poles, Rav Rothblatt found himself in front of a statue of the Christian deity.

In his sefer, Elokei Ovi B’ezri, the rov describes the horror of those days and how violated he felt being held captive in the church. That first night was Rosh Hashanah but because the Christian statues surrounded them, he and his fellow Jews could not daven. Their despair was palpable.

“There was a sharp sword at our necks…” Rav Rothblatt wrote. “We yearned to pour out our hearts…It was the Yom HaDin and the doors of Heaven were open. But we were forbidden to pray. Our souls wept only in secret. We focused our thoughts in tefilah, pleading from our innermost hearts without uttering a word aloud.”

The turbulence worsened as some of the Poles locked in the church with the Jews demanded the Jews remove their yarmulkas and caps, and stand barefoot in the church as a mark of respect.

According to Rav Rothblatt, he and other pious Jews wrestled with the question of whether acceding to these demands was included in the issur of avodah zorah. If so, they would have to submit to violence and perhaps death rather than transgress.

As Polish tempers flared, the rov sat on the floor with his hat on as the Jews closed ranks around him, hiding him from view. Amidst ugly murmurs and threats from the Poles, the night passed without an eruption of violence.

In the morning, the Germans separated the local Siennica residents—both Jews and Poles—from the refugees, and ordered the former to return home. The refugees, among them Rabbi Margulies, were detained in the church for several more weeks, the statues blocking them from pouring forth the heart-wrenching tefillos they ached to express.

During these days, in addition to the distress at not being able to observe the sacred days of Yom Kippur and Sukkos properly, the rov was overwhelmed with complex halachic shailos, knowing his guidance could spell life and death for his questioners, and for other Jews in dire straits.

HEART-WRENCHING DILEMMAS

The first moral and halachic dilemma concerned the Nazi’s accusation, the day after the roundups and detention in the church, that two German soldiers had been killed by Jews. One of the suspects was supposedly among the prisoners in the church. The Jews were ordered to hand him over to the Nazis or they would set fire to the church and burn everyone inside. Was it permissible to turn him over to save the community?

The same day, Rav Margulies was faced with another appalling question. The Germans had tortured some local Jews until they were half dead, and then ordered other Jews to bury them alive, or be killed. Should they refuse and lay down their lives?

Then a major quandary arose when the Germans appointed a three-man committee to distribute slips of paper for work. The committee of pious Jews turned to Rav Margulies. Should they carry out this assignment, knowing these slips of paper might lead fellow Jews to their death? Would it be best to put them down and tell the prisoners they could decide for themselves?

Yet another bitter conflict arose when Yom Kippur came, the refugees were still locked in the church. Some women insisted on lighting a candle for Yom Kippur and reciting a brocha. They felt strongly it would be a zechus for the survival of the community and their own families. Others strongly opposed this move as it violated German orders and posed a danger to the group. Tensions rose and the rov was called upon to pasken.

At a certain point, Rav Rothblatt relates in his memoir, the Jews were removed from the church and interned in a local school. From there it was theoretically possible to escape to the forest and a number of people were determined to save their lives in this way. The problem was it would involve killing the few Nazis guarding the school. Escaping, and certainly killing German guards, would certainly mean a death sentence for many of the Jews left behind.

The would-be escapees were torn. Instinct told them the community was doomed anyway and they should save their lives. But how could they do so if other Jews would be murdered in reprisal?

Hidden in Thunder does not record the halachic decisions Rav Margulies or Rav Rothblatt reached in these life-and-death scenarios. Those who seek this information are directed to Sh’eilos Ut’shuvos Mi’gei Hademaos, a halacha sefer and rare historical document in which the author dwells on some of the anguished shailos he paskened from the church in Siennica.

Farbstein notes that “the extremely complex questions he faced in that church tormented him so much” that for many years after the Holocaust, Rav Margulies was consumed with clarifying them and with explaining the nightmarish realities in which they arose.

The historian goes on to explain that these haunting questions “followed Jews everywhere during the Holocaust.” Situations where Jews seeking to escape might endanger those left behind were far from unique, and these dilemmas were brought to rabbonim in ghettos and concentration camps all across Nazi-occupied Europe.

The fact that so many wrenching quandaries arose at the same time in one community being held prisoner in a church, and were recorded in the writings of two of the rabbonim there, makes the story of Siennica a microcosm of the Holocaust with its unfathomable tragedy.

But it also stands out as a symbol of Jewish courage and heroism, in the inspirational image of Jews clinging to Torah law even at the crossroads of life and death.

RABBONIM IN SOME CASES OPPOSED ESCAPE

The questions these Jews raised continue to resound across the decades. Does Torah law and ethics restrict the saving of lives? From an incident described by Rav Rothblatt in his Elokei Ovi B’ezri, one can see there were indeed cases in which certain potentially life-saving acts were prevented by revered rabbonim.

The incident mentioned in the rov’s memoirs, cited by Farbstein, was when he was imprisoned in a local shul with the Jews of Adamav—a Polish shtetl neighboring Siennica. The Nazis had warned that if anyone was found missing during the daily head count, they would kill everyone.

In response, the Jews formed a committee tasked with preventing individuals from escaping and endangering the lives of the rest. The committee was headed by Rav Rothblatt and a refugee rabbi from Lublin, Rav Aryeh Leib Landau, known as the “Gaon of Kalbiel,” one of roshei yeshiva of Yeshiva Chachmei Lublin.

The daas Torah of these leaders seemed to demonstrate that certain values supersede the importance of saving lives, because without them life itself loses meaning. This was evident in many cases when survival for some meant handing over others to be killed or intentionally endangering the lives of fellow Jews.

HER RESCUE NOTE FELT LIKE A BURNING FLAME

A haunting dilemma about whether to attempt an escape when it puts other Jews at mortal risk is vividly recalled in the memoirs of another rov, Rav David Kahane of Lvov, cited in Hidden in Thunder.

Originally published in Hebrew, Rav Kahane’s Holocaust memoir, Lvov Ghetto Diary, bears witness to the systematic destruction of 135,000 Jews in the city of Lvov by the Nazis with the active help of Ukrainians. Recalling the war years, he writes, “To this day . . . my heart still trembles with terror.”

In the first part of the book, Rav Kahane, rov of the small town of Tykocin in Ukraine, is living in the Jewish ghetto with his wife and daughter in dire circumstances. He is then deported by the Nazis to the notoriously brutal Janowska slave labor camp, where conditions are much worse. There he witnesses daily tortures where dignified rabbis are forced to sing and dance until they collapse, and daily hangings of innocent prisoners from a gallows erected near the camp kitchen.

One day, a note from his wife managed to reach him, informing him that a Catholic priest was offering him refuge and he should make every effort to escape. Rav Kahane refers to this note as a “burning flame” that he was afraid to hold. He writes:

“…The note meant life, whereas each day in the camp meant death. Every one of us wanted so much to live, to live at any price! To live as a free man and witness Hitler’s defeat!

“I can hardly find the words to describe the inner struggle that raged within me during the roll call. Without having gone through the experience of a slave labor camp, one simply cannot understand this life-and-death struggle.

“To me it seemed then that in my hand I held a burning flame, not a written note from my wife. And I decided to let the opportunity [to escape] pass.

“I did not even tell my friends about it. I knew full well that for every escaped prisoner, four or five other Jews would be shot at morning roll call. Escape under these conditions runs counter to Jewish morality and law. Why should you regard your blood as more red than others, your life more worthy than theirs? Perhaps the opposite is true?

“So I remained in the camp…”

No Options Left

As conditions in Janowska grew more violent and thousands more died or were murdered, Rav Kahane came to the realization that all the prisoners were doomed and changed his mind about the ethics of escaping. There were no options for survival left for anyone, he felt, whether or not anyone escaped.

His memoir describes his hair-raising escape in April 1943, how he first went into hiding on the “Aryan side” and then made his way in trepidation to the Uniate Catholic church his wife had described in her note.

There he discovered to his amazement and relief that the Greek Catholic archbishop, Andrei Sheptytskyi, was sincere in his offer of shelter.

Sheptytskyi and his brother, Abbot Kliment, and the monks in the Uniate Catholic church hid Rav Kahane and about a dozen other Jews until the Liberation, while his wife and three-year-old daughter found refuge in a Greek Catholic convent.

In an interview in his later years, Rav Kahane notes that he began writing his journal while in hiding, describing the agonies of the Lvov ghetto before moving on to the horrors of the Janowska slave labor camp, followed by his months of hiding in the church.

His harrowing Diary is one of the few eyewitness accounts to emerge from the Lvov ghetto. An excerpt follows below.

MI’MAAMAKIM… FROM THE DEPTHS, I CALL YOU

“Meanwhile, September was drawing to a close,” the rov writes in his diary. “The bloody year 5703 [1943] was about to end. On motzoei Shabbos, September 1943, Jews in the free world were getting ready to recite Selichos… The first day of Rosh Hashanah that year fell on Tuesday, September 30, and Yom Kippur would fall on October 9.

“I was alone, cut off from my people. No kedusha, no tefila betzibbur, no siddur. No Jews.

But since I kept an accurate record of Shabbosos and yomim tovim, I was able to commune in my thoughts with Klal Yisroel during these holy days. “I spent the Aseres Yemai Teshuva in the very heart of the Uniate Catholic church…

‘Mi’maamakim kerosicha, Hashem, From the depths I call on You, Hashem!” With these words I poured out my heart before the Eternal G-d…”

Rav Kahane survived the war and emigrated with his family to Eretz Yisroel in 1949, settling in Tel Aviv. He served as chief rabbi of the Air Force and later as chief rabbi of Argentina in the 1960s and 1970s, before returning to Eretz Yisroel and making his home in Yerushalayim. He died in 1998 at the age of 95.

*****

‘ONE FROM A CITY, TWO FROM A FAMILY…’

Rav Eliezer Paltiel Rothblatt and Rav Shaul Dovid Margulies, who first met in the church in Siennica after being forced inside by Nazi thugs, were two of only a handful of Polish rabbonim to survive the Holocaust.

Their release from Nazi clutches after being locked in the church was just one of many miracles they experienced.

In the winter of 1940, Rav Rothblatt experienced a personal neis Chanukah when he managed to cross into the Russian-occupied zone with his wife and daughter. There he joined his father, Rav Shia Usher Rothblatt, the rebbe of Siedlce, who had already smuggled across the border.

His extraordinary memoir, Elokei Avi B’ezri, goes on to describe how the family was arrested and exiled to Siberia where most of them managed to survive the harsh living conditions. The elder Rav Rothblatt, however, passed away in Khazakhstan in 1941.

After the war, Rav Rothblatt served as one of the leading dayonim in the DP camps, before accepting the post of chief rabbi of Bogota, Columbia. In his later years, he settled in Boro Park where he opened a shul and beis medrash. He passed away in 1998.

Rav Margulies, in turn, was released from captivity in the church of Siennica after a number of weeks and immediately fled to Vilna, where he became one of the leaders of the Union of Exiled Rabbonim. He tried desperately to reach Eretz Yisroel. His name appears on the list of rabbonim applying for immigration certificates that Zoach Warhaftig, an Israeli lawyer and rescue activist, sent to Yerusholayim on March 26, 1940.

When these efforts failed, Rav Margulies turned to other avenues of escape. He joined hundreds of Jews seeking to obtain Japanese visas through the Japanese consul Sempo Sugihara, one of the chasidei umos haolam who saved thousands of Jews with his visas. He ultimately made it to Shanghai with students of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin where they spent the rest of the war years with the Mir Yeshiva.

Rav Margulies later emigrated to the United States where he accepted a post as rav in Coney Island, Brooklyn, and afterwards, became the rov of Kehilas Degel Yisroel in Queens. He died in 1988.

*****

‘HELP YIDDEN ESCAPE!’

“When I was imprisoned in the camp ghetto under the wicked Nazi oppressors,” Rav Yehoshua Grunwald, the “Chuster Rov,” wrote in Chesed Yehoshua, we questioned whether it was permissible to escape or to help others escape. After all, Jews are responsible for one another… Escape could cause innocent people harm and suffering.”

Rav Grunwald expressed his conviction that this reasoning did not apply at that time. Hungary had been occupied by the Nazis and ghettos had been established in some towns, a sure precursor to deportation and death.

Escaped Jewish prisoners Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler had by then published the Auschwitz Protocols which revealed to the world the Nazi slaughter and crematoria operations at Auschwitz, and the butchering of millions of Jews.

Before making their escape from the death camp in April 1944, the two men had overheard Nazi guards at Auschwitz joke about the trains full of Hungarian Jews they were expecting to soon arrive. They had witnessed the extra ramps being built near the railway tracks in the camp that would take the victims from the trains straight to the crematoria.

Although this information was not included in the Auschwitz protocols, it was circulated among some Hungarian and Slovakian Jewish leaders. Rav Grunwald thus had no illusions about what lay in store for the Jews of the Chust ghetto. He believed the entire community had been condemned to death, and urged his followers to help whoever could escape to do so.

“I considered it a great mitzvah to help Yidden escape, so that there might at least be a partial rescue and the remnants of our people would not, Heaven forbid, be lost,” he wrote in his sefer. “And this is what we did for [Jews who sought to flee], giving of our advice and counsel.”

“In retrospect,” the rov noted, “it is clear that most of those who fled survived, while those who stayed behind were murdered by the cursed reshaim.”

Rav Grunwald who survived Auschwitz, served as one of the leading dayonim in the DP camps and later in the survivor community of Paris. He and fellow survivor Rabbi Eliezer Paltiel Rothblatt (who returned from Siberia after the war), were deeply involved in resolving halachic questions related to agunos, women whose husbands had disappeared in the war and sought to remarry.

In the late 1940s, he settled in New York. He died in 1969 at the age of 60.