Lag Ba’omer Trumps Lieberman

Now that Lag Ba’omer has come and gone, nothing else seems to be of much interest anymore. Even Avigdor Lieberman’s entry to the government and swearing-in as Minister of Defense was delayed because of Lag Ba’omer.

On Wednesday morning, Yuli Edelstein, the Speaker of the Knesset, asked me if the chareidi Knesset members would be returning from Meron that night, or even the following morning. The Knesset’s sitting on Wednesday had been shortened because many members of the Knesset had announced their intentions to leave for Meron during the daylight hours in an effort to be there before shkiah. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Binyomin Netanyahu and Lieberman had already signed their agreement, and Lieberman wanted to be sworn in as a minister and as the Minister of Defense – and that needed to take place in the Knesset plenum. At the same time, according to Knesset regulations, the agreement could not be discussed until it had been on the Knesset table for 24 hours. Lieberman therefore pressed for a special Knesset sitting to be held on Thursday, and that was what prompted Edelstein’s question. Before I could respond, though, MK Yaakov Litzman’s aide answered for me: “They will all be returning on Thursday night.” Thus, if someone tells you that the festivities in Meron have an effect on the discussions held in the parliament of the State of Israel, you can believe him.

There were some other incidents of note, as well. For one thing, there was the case of the Border Guard police officer who struck an Arab in a Tel Aviv supermarket. The episode became a topic of discussion throughout the country and was discussed even in the Knesset. The police were forced to respond to accusations of brutality. Their response was that the Arab himself was not all that innocent. The fact that two police officers needed medical treatment after the incident was evidence of that.

What makes this story interesting is the fact that, at the same time, a video was posted online that showed a yeshiva bochur jaywalking and being accosted by a police officer. In the video, the policeman can be seen beating the bochur and dragging him on the ground. The bochur’s yarmulka falls off and the policeman is utterly indifferent. This incident is no less brutal and shocking than the beating of the Arab in Tel Aviv, yet no one uttered a peep in protest in this case.

There were other incidents as well, but the mass pilgrimage to Meron on Wednesday and Thursday eclipsed everything else that took place in the country.

Another story of note was the state comptroller’s report on Prime Minister Netanyahu’s travel expenses, including the allegations that he traded his airline points illicitly and that other parties had paid for his two children’s travel expenses. Some have claimed that this report will soon develop into criminal charges. In our state, which has the habit of devouring its residents alive, anything is possible. Most likely, though, is that now that the coalition has expanded with the addition of Lieberman’s party, Yisrael Beiteinu, Netanyahu will enjoy a quiet term as prime minister.

Meron Mishaps

If you want to know whether “Operation Meron 2016” was a success, it depends on whom you ask. If you ask the thousands of people who stood at bus stops and waited in vain for buses to arrive, you will certainly be told that this year represented yet another failure.

Moreover, it would appear that they are correct. There was a failure, at least in the realm of public transportation, and it was a major failure indeed. Tens of thousands of people purchased bus tickets from various companies and in various cities, and then it was discovered that there simply weren’t enough buses to provide for the demand. As a result, many people were forced to wait for lengthy periods of time until their buses arrived. This was a deficiency in the service of even the largest companies, such as Egged and Kavim, as well as the smaller ones.

In some areas, it was clear at the outset that the bus companies would never meet the demand and expectations of the public. That may be due to the reductions in the price of public transportation (Aryeh Deri’s initiative of several months ago) or because of the urging of the police for people to use public transportation on Lag Ba’omer rather than traveling in private vehicles. Then there were the initiatives of mayors such as Meir Rubinstein of Beitar Illit and Yisroel Porush of Elad, which led unprecedented numbers of people to purchase tickets in advance. It should have been clear that not every ticket holder would see the inside of a bus. After all, how many buses are there in the State of Israel altogether?

Even on Wednesday night, the media was able to report on the large numbers of people waiting at the designated departure points – in Yerushalayim, in Bnei Brak, in Beit Shemesh, in Elad, and in Beitar Illit. I personally drove around to the various departure points for the buses of Egged, and I saw many people waiting and far too few buses arriving to pick them up. I also went to Geulah, to the area designated for the Hoffman bus company. Hoffman is one of the oldest companies in Israel that organizes transportation to Meron. An entire street in Geulah had been closed off to serve the Hoffman buses, which, of course, were rented for these two days alone. I saw the people waiting there, and I saw the police barrier that had been erected to keep cars off the street. But I did not see any buses.

Even these mishaps, though, were ultimately lost in the greater picture. Hundreds of thousands of people danced to the music in Meron and shed tears at the grave of the holy Tanna Rav Shimon bar Yochai. Dozens of groups worked hard to make the day a smooth one for the visitors, and many people spent three days engaged in various forms of chesed in the area. Let us look only at those aspects of the day.

A Blaze at the Entrance to Yerushalayim

Another story associated with Lag Ba’omer was the large fire that burned last Thursday at the entrance to Yerushalayim. The conflagration was so severe that the police and firefighters evacuated some residents from their homes. Some of those people were residents of the small moshavim outside Yerushalayim, on the road toward Tel Aviv, while others lived in Ramot, the largest chareidi neighborhood in Yerushalayim. Even some residents of Romema were asked to leave their homes. It was quite frightening.

The fire focused public attention on another issue: that of the huge high-rise buildings being constructed in the neighborhood of Romema. These are initiatives that are greatly expanding the supply of apartments available for the chareidi public in Yerushalayim, although the typical young couple cannot afford an apartment in any of these complexes. The purchasers, by and large, are Jews from chutz la’aretz.

Many times already, I have made the argument on various platforms that whoever has approved the construction of these hundreds or thousands of apartments is not looking at the larger picture. Where will the hundreds of children who grow up in those apartment buildings go to school? Where will they play? Where will all the residents park their cars? What will prevent the entire area from turning into one large traffic jam? Has anyone thought about these issues? In the aftermath of the fire, I can add another point: In the event of an emergency evacuation, chas veshalom, how will everyone get out of those buildings quickly and safely?

The “Yeshuos Room” in Meron

On my own visit to Meron, I met a young man named Nachman Schnitzer. He was standing at the entrance to the “yeshuos room” at the tziyun of Rav Shimon bar Yochai, dispensing radiant smiles and hospitality to everyone who passed him. Coffee, sugar, tea bags and cookies were available to the visitors to the tziyun. At the end of an arduous trip to Meron, or before an equally arduous trip back home, a sweet cup of coffee can seem like a yeshuah in its own right.

If the sacred site of Rav Shimon bar Yochai’s kever is visited by one million people each year, for argument’s sake, then the yeshuos room receives twice that number of visits. Every visitor arriving at the kever enters the room to enjoy a hot drink after the exhausting trip to the site. Then, on the way out, the same visitor will return for a second drink to soothe his throat after numerous perakim of Tehillim and to fortify himself for the lengthy trip home. You can imagine, then, that we all owe a great debt of gratitude to the people who maintain this small room.

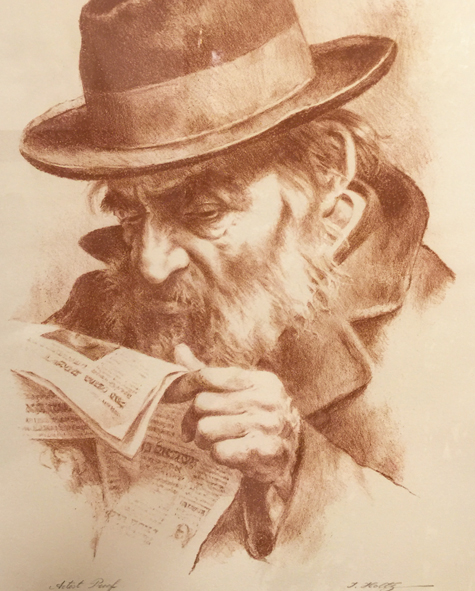

Meron is a place that every Jew is drawn to visit. There is some inexplicable force that impels the Jewish soul to go there. Anyone with a broken heart or in emotional torment will make his way to Meron and will return home a different person. Everyone gravitates to Rav Shimon bar Yochai in his own time of need. The site seems to have a unique power to cheer up the disconsolate and to transform despair into hope.

I, of course, am like every other Jew in this respect, and I visit Meron from time to time. On every one of my trips, I help myself to a cup of hot coffee upon arrival, and while I wait for the beverage to cool, I find myself examining my fellow visitors, in particular the regulars at the site. They are all special people; at times, they are also bizarre. Sometimes I also make my way to the nearby tent, where rice, soup and other foods are provided. But I recently realized that I never thought to investigate who was responsible for the food in the tent, or for the beverages that are readily available in the room next to the kever. It is as if it was simply another public service, as if someone owed something to me. It almost seemed natural for such a room to exist in a place like this. But this time, something piqued my curiosity and I asked the regular visitors to enlighten me as to who was responsible for the facility.

“Look, there is Nachman Schnitzer,” they said, pointing to a nearby young man. “Talk to him.”

“I’m Nachman Schnitzer,” he confirmed when I approached him, “but this room belongs to my father, not to me. And he isn’t here now.”

“Are you always in Meron?” I asked him.

He confirmed that he was indeed in Meron all year long. In general, his father is in charge of the room, but during the week of Lag Ba’omer, the responsibility falls to Rav Tzion Kuperstock. In the room, visitors are provided with coffee, tea, cookies, and milk 24 hours a day, all year long, and especially on Lag Ba’omer.

Nachman and his father see to it that all the provisions are there at all times. The milk is purchased from the grocery stores on the moshav of Meron or directly from Tenuvah. The water flows from large tanks that refill automatically. The room was originally designated for their use by Rav Menashe Eichler, who was in charge of the site. “That was many years ago,” Nachman related. “You will be able to learn a lot more if you speak with my father, but he is busy right now. He is being interviewed by a radio station in Paris, which sent a team of reports to Meron for Lag Ba’omer.”

I refer to this room as the “yeshuos room,” and Reb Shraga Schnitzer, Nachman’s father, relates that over the course of his decades in Meron, he has seen many yeshuos in the merit of aiding the visitors to this sacred site. He remembers the room from his own childhood. He inherited the privilege of caring for it from his parents, and they themselves received it from their own predecessors.

“The building over the tziyun,” he relates, “was constructed by Rav Avrohom Galanti at the behest of the Arizal, to provide the visitors with shelter from the heat in the summer and from rain in the winter. Above all, though, it was for them to have a place to eat and drink.”

It takes a certain single-minded fixation to pursue such a cause, and Reb Shraga possesses that crucial trait. Before his marriage, he informed his future wife that she would be marrying a young man who would be dedicating at least half of his life to Rav Shimon. “It’s part of my neshamah,” he told her.

Shraga himself is responsible for improving the “service” in the room by providing coffee and cake around the clock, as well as full meals on Shabbosos and Yomim Tovim, including the Seder night and the night of Purim.

“Do people appreciate what you do for them?” I asked him.

Reb Shraga laughed. “I don’t need anyone to thank me. I just want people to be provided for. If someone asks how he can thank me, I suggest bringing milk for the room. The word for milk, ‘cholov,’ can be an acronym for anything a person may need: ‘Chayav lihiyot bruit – There must be health,’ ‘Chatunah lihiyot bekarov – A wedding will be soon,’ or ‘Chayav lihiyot ben – There must be a child.’ It includes everything.”

Dancing with the Talmidim of Ner Moshe

In my own neighborhood of Givat Shaul, even those who do not travel to Meron can still enjoy a beautiful Lag Ba’omer bonfire in the neighborhood, one that is both joyous and moving. It begins at Maariv at the Zupnik shul, where almost all the local residents who haven’t gone to Meron gather. After davening, there is a public auction, where the highest bidder receives the right to honor the rov with lighting the bonfire. The bidding, by the way, is conducted in dollars.

The rov is Rav Avrohom Yitzchok Ullman, the rov of the shul and of the neighborhood; he is also a member of the Badatz of the Eidah Hachareidis. He is a brilliant man and one who is highly admired by the public. After the auction, the crowd adjourns to the street behind the shul, where Rav Ullman uses a long torch to light the oil-soaked rags that have been placed in a large bin – and then the celebration begins. A car blasts Lag Ba’omer songs in the street, and spirited dancing erupts. Almost everyone in the neighborhood is present, except the children who are busy lighting their own bonfires on neighboring streets.

The celebration is always enhanced by the talmidim of Yeshivas Ner Moshe, which is located in Givat Shaul. Ner Moshe is a yeshiva whose talmidim come from outside Eretz Yisroel, mainly from America. This year, they were also joined by the talmidim of Yeshivas Acheinu, Rav Dovid Hofstedter’s kiruv yeshiva. Boys clad in white shirts, black jackets and hats danced alongside others sporting much more colorful garb. It was an incredible scene.

The Army Does Not Need Immigrants

The State of Israel is prepared to absorb immigrants. It isn’t that this country is all that attractive a destination, but there are other countries where the situation is worse, both economically and in terms of security, than it is here. The following is the picture painted by the aliyah statistics of the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption, the Jewish Agency, and the Population Administration.

In 2014, there were 11,878 immigrants from the countries of the former Soviet Union (Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, and the South Caucasus). The final figure for 2015 is expected to be 13,430, once it has been calculated, and it is predicted that there will be 15,100 immigrants in 2016.

As for Western Europe – consisting of Great Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, Holland, Scandinavia, Spain, and Portugal – in 2014 there were 8,829 immigrants from those countries, while in 2015 there were 9,280. This year, there are expected to be another 12,000 immigrants. The Jewish Agency and the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption believe that about ten thousand immigrants will come to Israel from France alone. From the countries of Eastern Europe – Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, and Romania – there were 237 immigrants in 2014 and another 192 in 2015. This year, an additional 245 people are expected to immigrate from those locales.

Now for North America: In 2014, over 3,500 people immigrated from the United States and Canada (with 353 from Canada). In 2015, the final figure is expected to be 3,385 (of which 385 immigrants were from Canada). In other words, the total number of immigrants in 2015 was slightly less than the year before. The expectation is that in 2016 there will be another 3,600 immigrants from the two countries together, with 400 of them from Canada.

If any of you, in America or Ukraine, are considering aliyah but are worried about national service, there is good news for you: From now on, immigrants of 22 years of age or more (who arrive in Israel beginning on January 2016) will not be subject to the draft at all. Until now, the requirement for military service has applied to olim up to the age of 26, although the authorities were always in the habit of cutting corners for immigrants.

Colonel Eran Shani, the commander of the Meitav induction base, explained that a major factor leading to the blanket exemption was the fact that military induction caused many immigrants to lose their jobs. Sources in the government maintain, though, that the main impetus was consideration for the Jews of the Diaspora, particularly those from France, who seek to find refuge in Israel from the threat of terror in their native lands. A senior official in the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption added that in any event, “The immigrants tend to be placed in jobs that are meant solely for them to pass the time until their discharge.” For those who insist, there is an option to enlist even after the age of 22.

Apparently, the army is not in need of recruits.

A Remarkable Reunion

Recently, someone told me an incredible story about a man who spent Pesach in Hungary as part of a group of retirees from Israel, celebrating the Yom Tov in a glatt kosher hotel. According to the account I was told, the protagonist of this story asked the other members of the group to join him for a few hours in an effort to find his mother’s grave in one of the Jewish cemeteries. When they arrived, they discovered that the cemetery was in a state of severe neglect. With the exception of one well-preserved kever near the entrance, all the other graves had been ruined. It was difficult to read the writing on any of the tombstones.

The minyan of Israelis, whose collective age totaled nearly 700 years, scattered throughout the cemetery in a concerted effort to locate the grave, but their efforts were in vain. Despairing of success, they found themselves sharing the pain of their elderly comrade, but as they slowly shuffled out of the cemetery, one of them suddenly cried out, “Here is the kever!” As it turned out, the well-preserved grave, for which none of them had bothered to spare a glance, was actually the one they had sought. The son recited Kaddish in a trembling voice, and the entire group felt that they had been through an experience that bordered on the supernatural.

The group hurried to the non-Jewish security guard and asked him to solve the riddle of the well-maintained kever. “I have no idea about the details,” he replied apathetically, shrugging his shoulders between puffs on a cigarette. “There is a woman who comes to the grave every week.” He did not know the woman’s name, nor could he explain why a non-Jewish woman would be visiting the grave of a Jewish tzadeikes, but he was able to provide her address. “She lives in the first house facing the cemetery.” The Israeli group hurried to the location he had indicated.

The woman, who was herself approaching old age, opened her door and was surprised to find herself facing a group of distinctly Jewish-looking men. She ushered them into her home, and the son of the nifteres asked, “Can you please tell me why you have been maintaining the kever of a certain woman who is buried in the Jewish cemetery?”

The woman shrugged and said simply, “What type of question is that? She was my mother.”

When I heard this story, I telephoned the protagonist – the supposed son of the nifteres and the brother of the woman who has been maintaining the kever – to verify the details. He is a longtime resident of the community of Rechasim in northern Israel and he was amused by the version of the story I had been told. “People have an incredible way of changing the details of a story,” he said. “I am a member of the sixth generation of my family in Eretz Yisroel. My mother was born here and lived a long life; she was buried in Eretz Yisroel and I visit her kever regularly.”

Does that mean the entire story was fabricated? As it turns out, the answer is no.

“The true story is as follows,” he said. “I was in a hotel in Ukraine – in the Carpathian Mountains, to be more precise – and the program included trips. On one of those trips, which I myself didn’t attend, one of the men asked everyone else to allow the tour bus to enter the town where he was born, which they were passing in the course of their journey. His purpose was to visit his mother’s kever. When he arrived, he saw that the kever was well maintained, and he asked the guard who was taking care of it. ‘There is an elderly woman who tends to this grave,’ the guard replied. He arranged for the two to meet, and the man discovered that the woman was his sister. The two had been separated during the war, and neither had been aware that the other was still alive.”

The man could not tell me the name of the cemetery or the town where the incident took place. “It was one of the towns near Ungvar, but I don’t know exactly which one. I can’t give you any further details.” He did confirm, though, that almost all the guests at the hotel were similar to him in age and background. “I have already been contacted by several well-known speakers from Bnei Brak who heard about the story and wanted to confirm the details,” he added, “and I will give you the same suggestion I gave them. The entire vacation was arranged by the Shai Bar Ilan travel agency. You can call them to find out who the guide was, and he can tell you the identity of the man in question.”