It may surprise many readers to learn that here, too, on American soil, we also have a mesorah of Torah, Yiddishkeit and Pesach Sedorim going back already hundreds of years. Even before the Revolutionary War, Jews were keeping Pesach in the American colonies.

In colonial New York and Pennsylvania – and even out in the remote prairie lands – Jewish housewives were scrubbing their dwellings, ridding them of any chometz before Pesach. Soldiers fighting on both sides of the Civil War during the years of 1861 to 1865 worried about how they would celebrate Pesach properly. Even Jewish Forty-Niners, who traveled westward after being gripped with gold fever during the California Gold Rush of 1849, imported matzos and other Pesach staples from the east at highly inflated prices.

REVOLUTIONARY WAR YEARS

The first siman in Shulchan Aruch concerning Pesach discusses the requirement to give maos chittim to those less fortunate than us. In the minutes of Congregation Mikveh Israel, a colonial congregation in Philadelphia, we find that on March 16, 1784, a mere ten years after the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, “the adjunta agreed that ten barrels of flour were to be provided for the use of the congregation and the poor (for the baking of Matzoth)” (The History of the Jews of Philadelphia, published by The Jewish Publication Society).

Aaron Lopez, a marrano who left Portugal and settled in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1752, was one of the leading merchants and patriots in Newport. During the Revolutionary War, he sheltered Jewish refugees in his Leicester, Massachusetts, home. He was a founding member and one of the leading contributors of the famous Touro Synagogue in Newport, the oldest shul in America, and was honored with laying its cornerstone.

Before Pesach of 1776, with British troops closing in on Newport, Aaron fled to Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Still, he made sure to send 100 pounds of flour to Newport in keeping with his custom to ensure that there was enough flour to bake matzos for the Newport community (The Colonial American Jew, 1492-1776, by Jacob Rader Marcus, Wayne State University Press).

Another Jew who lived in Newport was Moses Seixas (1774-1809). Moses was the Parnas of Touro Synagogue at the time of George Washington’s famous visit. The renowned letter from President Washington to the “Hebrew Congregation in Newport Rhode Island,” in which he writes that “happily the Government of the United States… gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance…” was addressed to “Moses Seizas, Warden.”

Moses was a recognized mohel and, in 1795, was one the founders of the Bank of Rhode Island. He worked in the bank as a cashier until the end of his life. George Gibbs Channing, a gentile who lived in Newport at the time, writes in his recollections, “I was well acquainted with Mr. Moses Seixas, cashier of the Bank of Rhode Island.” Tongue-in-cheek, he describes how Moses and his son Benjamin, also a cashier, were “in stature so short that I thought the vault or safe which occupied a portion of the cellar and was very shallow had been constructed with especial reference to their convenience!”

Channing goes on to tell a fascinating vignette of how he acted as the bank’s “Shabbos Goy.” The bank always kept one set of keys at his store, he explains. “On the Jewish sabbath Saturday, I was expected to take the keys to the bank when a Christian officer would be in attendance” to open the doors to the bank. For his assistance, he writes, “I always received some token, usually in the shape of Passover bread and bonbons resembling ears in memory of those cropped from Haman” (Early recollections of Newport, R. I., from the year 1793 to 1811, by George Gibbs Channing).

You guessed it. George was talking about matzos and hamantashen!

The Constitution of the United States was written during the Constitutional Convention in 1787. In 1788, after it was ratified by a majority of the 13 states, it became the law of the land. On July 14, 1788, the Federalists held a huge parade in Philadelphia to celebrate the occasion. Naphtali Phillips (1773-1870) – who married Rochel Hannah Seixas, Moses Seixas’ daughter, and who was president and trustee of Congregation Shearith Israel of New York for well over half a century – was a boy of 15 and in Philadelphia at the time of the parade. Years later, he wrote a letter to a friend, sharing recollections of that momentous event:

“The procession then proceeded…towards Bush Hill, where there were a number of long tables loaded with all kinds of provisions, with a separate table for the Jews, who could not partake of the meals from the other tables: but they had a full supply of soused [pickled] salmon, bread and crackers, almonds, raisins, etc. This table was under the charge of an old cobbler named Isaac Moses, well known in Philadelphia at that time” (American Jewish Archives, Jan. 1955).

Amazing! In 1788, at a parade celebrating the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, there were separate tables of kosher food under Jewish supervision. Even more amazing, there does not seem to have been any sushi served there!

CIVIL WAR ERA

In 1849, gold was discovered in California. This led to the Gold Rush. Thousands upon thousands of people – including many Jews – were struck with “Gold Fever” and rushed to seek their fortune in many pioneer towns on the American West. Nevada City, California, was one such Gold Rush city, and by the 1850s was home to many frum Jewish families.

Aaron Baruh (1823-1907) lived in Nevada City with his family. According to records, the family “maintained separate dishes for Passover” and ordered matzos from San Francisco. Aaron himself “fastened a mezuzah to every doorpost in his house.” Not only that, but when Aaron got married in 1861, his kesubah was registered with the county as the official document attesting to his marriage (The Jews in the California Gold Rush by Robert E. Levinson, Judah L. Magnes Museum).

1861 also brought with it the outbreak of the American Civil War. There were Jewish families living in both the Union and the Confederate parts of America, and this led to Jewish soldiers fighting on both sides of the battle. In The Jewish Messenger, a New York paper, Private Joseph Joel of the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry division penned a captivating and humorous article in 1866 about one memorable Pesach during his time in service:

“In the commencement of the war of 1861, I enlisted from Cleveland, Ohio, in the Union cause… we marched to the village of Fayette, to take it, and to establish there our Winter-quarters. Being apprised of the approaching Feast of Passover, twenty of my comrades and co-religionists belonging to the Regiment united in a request to our commanding officer for relief from duty, in order that we might keep the holydays, which he readily acceded to.”

This commanding officer just happened to be Rutherford B. Hayes, who later became the 19th president of the United States and with whom Private Joel later kept in touch! Letters informing the president of births in Joel’s family and from the president congratulating Joseph can be accessed through the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library. According to Nan Card, Curator of Manuscripts at the Hayes Presidential Center, “Joseph Joel was a dear, dear friend of President Hayes.”

Private Joel’s account continues: “Our next business was to find some suitable person to proceed to Cincinnati, Ohio, to buy us Matzos. Our sutler being a co-religionist…readily undertook to send them. The morning of Erev Pesach a supply train arrived in camp, and to our delight seven barrels of Matzos. On opening them, we were surprised and pleased to find that our thoughtful sutler had enclosed two Hagedahs and prayer-books. We were now able to keep the seder nights, if we could only obtain the other requisites for that occasion.

“We… decided to send parties to forage in the country while a party stayed to build a log hut for the services. About the middle of the afternoon the foragers arrived, having been quite successful. We obtained two kegs of cider, a lamb, several chickens and some eggs. Horseradish or parsley we could not obtain, but in lieu we found a weed, whose bitterness, I apprehend, exceeded anything our forefathers ‘enjoyed.’

“We had the lamb, but did not know what part was to represent it at the table; but Yankee ingenuity prevailed, and it was decided to cook the whole and put it on the table, then we could dine off it, and be sure we had the right part. The necessaries for the choroutzes we could not obtain, so we got a brick which, rather hard to digest, reminded us, by looking at it, for what purpose it was intended.”

“I was selected to read the services… The ceremonies were passing off very nicely, until we arrived at the part where the bitter herb was to be taken. We all had a large portion of the herb ready to eat at the moment I said the blessing; each eat his portion, when horrors! what a scene ensued in our little congregation, it is impossible for my pen to describe. The herb was very bitter and very fiery like Cayenne pepper, and excited our thirst to such a degree, that we forgot the law authorizing us to drink only four cups, and the consequence was we drank up all the cider…” (courtesy of the Hayes Presidential Center, Fremont, OH).

On the Confederate side, soldiers struggled equally with observing Pesach properly. A letter sent from Adams Run on April 24, 1864 by Isaac J. Levy of the 46th Virginia Infantry Company E to his sister tells of how “Zeke [Capt. Ezekiel J. Levy of the 46th VA, Isaac’s brother]was somewhat astonished on arriving at Charleston…to learn that was the first seder night. He purchased matzos sufficient to last us for a week. The cost is somewhat less than in Richmond, being but $2 a pound. We are observing the festival in a truly Orthodox style. We had a fine vegetable soup… containing new onions, parsley, carrots, turnips… also a pound and a half of fresh kosher beef, the latter article sells for four dollars per pound in Charleston.”

Sadly, Isaac Levy was killed on August 21, 1864 in the trenches during the Siege of Petersburg, only a few months after writing this letter. He is buried in a family plot near the Hebrew Confederate Cemetery (the only Jewish military cemetery in the United States) in Richmond, Virginia.

Emma Mordecai (1812-1906), who recorded the fall of Richmond in her private diary, writes in an August 24, 1864 entry about hearing “the sad news of the death of Isaac Levy… He and his brother Ezekiel Levy have observed their religion faithfully, ever since they have been in the army, never even eating forbidden food.”

On August 30, after visiting with Isaac’s family, she writes, “Isaac was an example to all young men… A true Israelite without guile – a soldier of the L-rd… His parents and sisters mourn for him [but] are also full of Faith and Hope and submission. If all our people were like that family, we would already arise and shine for our light would have come” (The Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina).

Sometimes, though, the war brought Jews from the two opposing sides together.

One such incident happened when Myer Levy, a Union soldier stationed in an occupied Confederate Virginia town, noticed a little boy eating matzoh during Pesach and asked the boy for a piece. The boy ran into his house shouting, “Mother! There’s a ‘Yankee’ Jew outside!”

(During the Civil War, Southerners referred contemptuously to all Northerners as “Yankees.”)

To Levy’s relief, the mother came outside and invited him in to join the family for the Seder! (American Jewish Historical Society).

In the years immediately following the Civil War, Jews found themselves still living in many of the Gold Rush communities out West even though the rush years had already waned. Mokelumne Hill, a remote town in California, was one of the richest gold mining towns in its heyday. Due to its great distance from San Francisco, it was said – only partially in jest – that by the time any matzos reached Mokelumne Hill, the Yom Tov had already been observed!

Visitors to Mokelumne Hill can still see the pioneer Jewish cemetery which has twelve kevorim with matzeivos in Hebrew.

Aaron Harris lived in Yosemite Park, California. A storekeeper who arrived in Yosemite in 1874, he opened the first store in Yosemite in 1876, selling vegetables, butter, eggs and milk to campers. The store eventually evolved into the first camping business in Yosemite, renting cabins and camping equipment as well.

Wishing to celebrate Pesach properly, Aaron would order his matzos the previous year from San Francisco so that they would arrive on time for the next year’s Pesach! (The Jews in the California Gold Rush).

EARLY 1900’S

Two weeks before Pesach of 1891, Rav Binyomin Papermaster (1860-1934), who had learned under Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spector zt”l in Kovno, arrived in the remote prairie town of Grand Forks, North Dakota. Since it was right before Pesach, Rav Binyomin’s time was taken up procuring matzos and shechting birds for the Yom Tov. At a meeting on Chol Hamoed, though, Rav Binyomin founded the Congregation of the Children of Israel, the first shul in North Dakota, where he served for forty-three years. (The congregation still exists today, though, regrettably, it is no longer Orthodox.)

Isadore Papermaster, Rav Binyomin’s son, remembers how “Passover was always a busy season around our home. The supplies usually arrived around Purim… it grew to be the family’s job to take orders to deliver on foot, by wagon or wheelbarrow locally. Boxes were packed for shipping by freight to the outlying communities, some as far away as Montana.”

Rav Papermaster is buried in Grand Forks but has hundreds of descendants living all over the United States and Eretz Yisroel, many of them frum and carrying on his legacy.

Sophie Turnoy came with her mother and brothers to the United States in 1908 to join her father on a farm near Wilton, North Dakota, a town which had been founded less than 10 years earlier and had a population of about 300. Her grandmother, Sophie recalled, “was small, fragile, and very devout. She wore a black silk dress and sheitel of straight black hair over which she wore a black wool shawl. She made her living by running a little dry goods store. She arose before dawn every day… Before opening her store, she went to shul to pray… Three times a week my grandmother fasted. Also once a week she prepared a basket of food for some poor family who otherwise would have little with which to usher in the Sabbath. Her life was devoted to work, prayer and charity.

“Several days before Passover,” says Sophie, “my mother, sister and I set about getting our home ready for the holiday. Mother whitewashed all the walls and scoured the floors. She made the utensils kosher for Passover with scalding hot water. A stone was first heated in the range until it was red hot. It was then put into a very large pot of boiling water, making the water sizzle and hiss. The utensils were boiled for some time in this water. In addition, every piece of furniture was carried down to the slough and scrubbed” (“And Prairie Dogs Weren’t Kosher”: Jewish Women in the Upper Midwest Since 1855 by Linda M. Schloff, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1996).

Finally, here’s a story which took place in 1933 and became known as the “Matzoh Pardon.”

Rav Tuvia (Tobias) Geffen, who was born in Kovno, Lithuania, in 1870 and emigrated to Canton, Ohio, in 1903, was the rov of Atlanta, Georgia’s Congregation Shearith Israel from 1910 until his petirah in 1970 at the age of 99. Rav Tuvia led a most interesting life, though perhaps he is most famous for when the Coca-Cola Company made a corporate decision to allow him access to the list of ingredients in Coke’s secret formula when he gave it a hechsher in 1935.

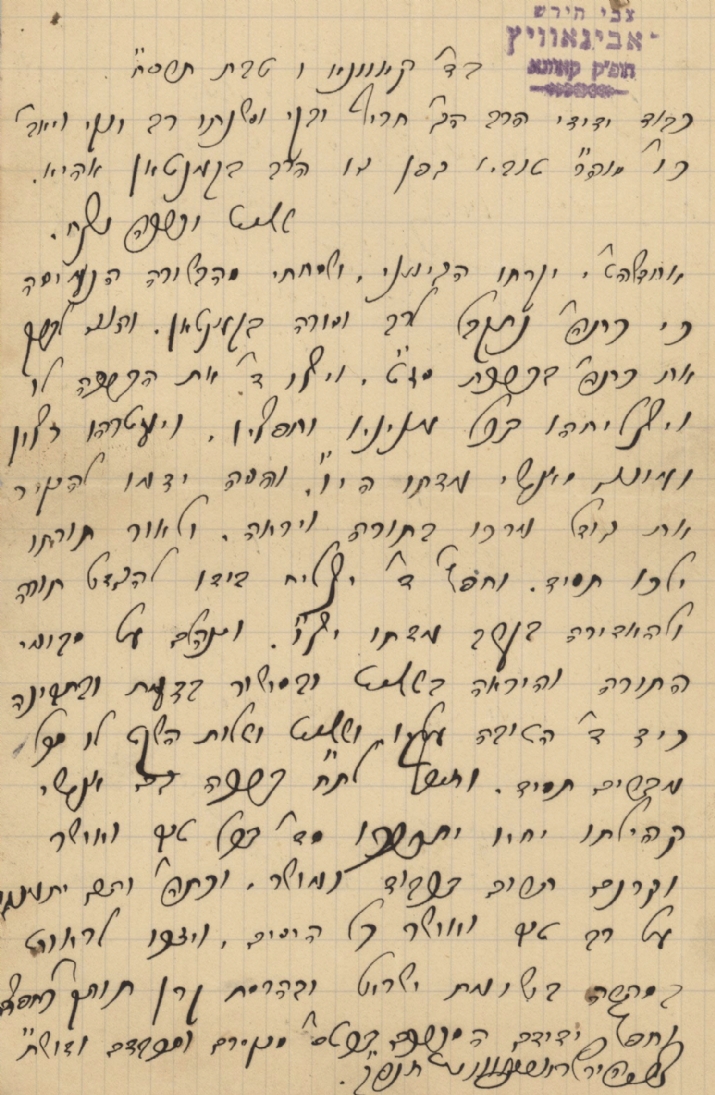

Just before Pesach of 1933, Rav Tuvia received a handwritten letter from a young Jewish prisoner in the Georgia State Prison in Milledgeville asking for matzos and a Haggadah. The rabbi sent these right away, along with a letter expressing interest in learning more about the prisoner.

The man wrote back, thanking the rabbi for the food, “which was like manna from the Heavens,” and apologizing for not responding earlier. He had been thrown in solitary confinement, he explained, because he’d refused to work during Pesach.

The young man, it turned out, was an unemployed bookkeeper from Philadelphia who had hitched a ride south in search of employment. Unfortunately, the ride he hitched was with a group of bank robbers from New York. Afraid he would report them to the police, the robbers forced him to remain with them at gun-point. Eventually, they were apprehended by state troopers just north of Savannah, Georgia, and the young bookkeeper was tried as an accomplice and sentenced to eight years in prison.

Rav Geffen inquired of the chief rabbi of Philadelphia and learned that he was acquainted with the young man and knew him to be upright, honest and of good character. Recognizing the opportunity for pidyon shvuyim, Rav Geffen wrote to the governor, Eugene Talmadge, asking that the prisoner be pardoned. “From the prisoner’s letter to me seeking Jewish religious items for the Passover holiday, I can readily understand that the boy has a deep religious feeling and also possesses character, sufficient to warrant my recommendation that he be granted clemency,” he wrote.

Two days after receipt of Rav Geffen’s letter, the governor ordered the prisoner released.

When asked how he knew about Rav Geffen, the young man related that he had mentioned his desire to obtain Passover items to a non-Jewish fellow prisoner. The non-Jew told him about Rabbi Geffen, who had been a neighbor of his family. In the end, the young man’s desire to perform the mitzvah of eating matzoh led him to contact Rav Geffen, which ultimately led to his freedom (autobiography of Rabbi Geffen, Our Family Story, Marjorie Goldberg, granddaughter).

Amazing how Pesach, our Festival of Freedom, was celebrated by Jews through thick and thin, in all places, and under all circumstances.

– – – – –

The American Jewish Legacy Passover Haggadah served as the springboard for most of the material in this article. Many thanks to them for their kind permission to use their work. Thanks as well to Rabbi David Epstein of the Western States Jewish History Association and to Nathan Tallman of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives for their assistance.