For two weeks before Shavuos this year, the Israeli newspapers were filled with discussions about the Six Day War. Part of the reason was the fact that we marked the passage of fifty years since the war, but even more than that, it was because of the decades-old protocols that had just been released. The State of Israel, like any country in the world, has classified documents, which are kept in the National Archives. The officials in charge of the archives have the authority to decide when it is acceptable to declassify secret documents. That is what happened recently in the case of the Yemenite children, when the decision was made to declassify many documents regarding the children’s fates. Three weeks ago, the government released many documents chronicling the events of the days leading up to the Six Day War, including transcripts of discussions in the government and the security cabinet.

The security cabinet is a panel similar to the cabinet itself, albeit possibly with fewer ministers. The difference is that the discussions of the security cabinet are classified. It is considered a violation of national security even to leak information from its meetings. Indeed, it is accepted that no aspect of the security cabinet’s meetings is ever leaked to the press.

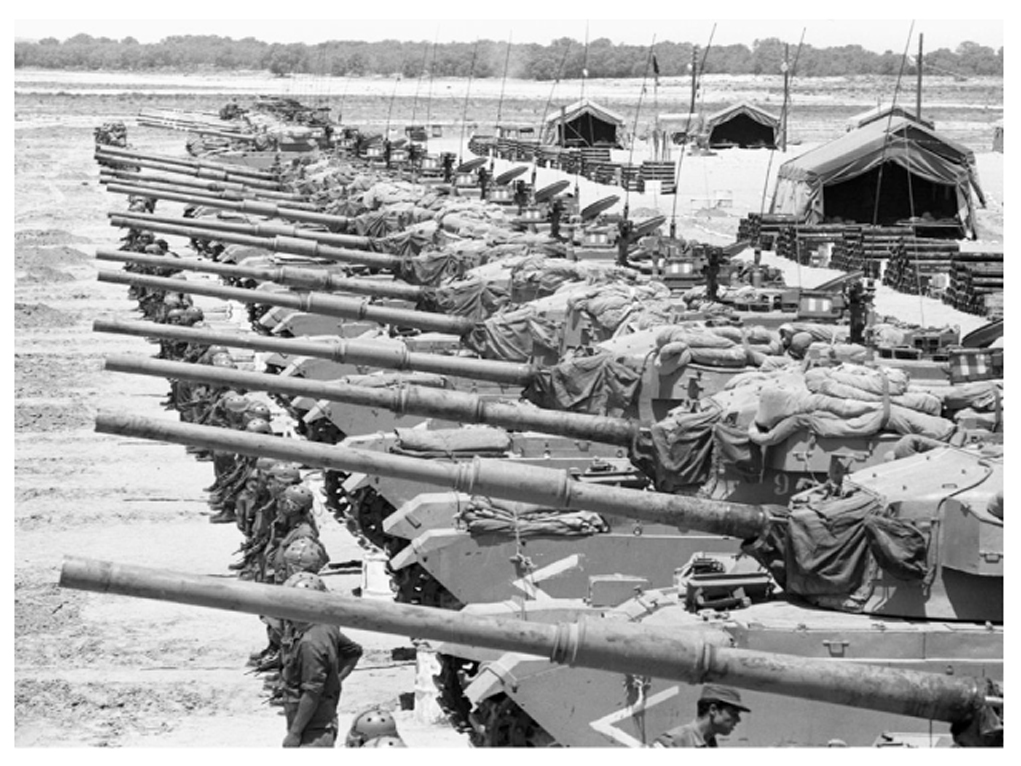

Most of the newspapers focused on the quibbling between the government ministers and the pettiness shown by people who were once hailed for their heroism. But the protocols can also teach us a lot about the miracles of those days. Government ministers and IDF officers alike had stressed that the entire country was in grave danger; for a while, there was a sense that all had been lost. The government discussions were pervaded by the sense that the country’s very existence was in question. Anyone who reads the protocols and relives the atmosphere of those days will appreciate the magnitude of the miracle that occurred.

Power Plays on the Eve of War

There is much to learn from the protocols that were released. Some of the ministers sound intelligent; others seem strange. Some did not know how to ask the right questions, while others never had answers. Some were arrogant; others were myopic. I read the statements made by pompous military officers who seemed to view the world through the crosshairs of a rifle. I read through a large portion of the protocols, and I have to say that while I thought the documents would open a window into history, what I saw instead was an account of pure panic.

Most of the newspapers that quoted excerpts of the protocols actually missed the main point: The nation was in grave, tangible danger. The army knew that attacking the Egyptian airfields, even by surprise, was liable to cause us tremendous losses. Nevertheless, they emphasized that the delay that others proposed – mainly for the purpose of coordinating the attack with the United States – would be more dangerous. The government feared the prospect of falling into disfavor with the Americans, on whom Israel has always relied. One can only conclude that we lived then, as we do today, purely on the basis of miracles.

Just before the war broke out, there was tremendous pressure brought to bear on Prime Minister Levi Eshkol to surrender the position of Minister of Defense, which he also held at the time, and to allow it to be taken over by Moshe Dayan. There were stormy protests in Tel Aviv. Eshkol did not know what to do. Dayan was a member of the rival Rafi party. In one of the cabinet meetings just before the outbreak of the war, Eshkol informed the cabinet, “Begin has come to me and has told me that we must broaden the government. He has come to suggest a tremendous salvation for Israel. He has offered for Gachal and Rafi to join the government. He said that Ben-Gurion would be the prime minister and I would be his deputy. Or perhaps Begin himself would be the prime minister and I would be his deputy. Or perhaps I would be the prime minister and Ben-Gurion would be the defense minister. I was somewhat surprised by that. But I told him that these two horses [Eshkol and Ben-Gurion] will never pull the same cart.”

Rafi, the party that broke off from the ruling Mapai party headed by Levi Eshkol, had ten members at the time, including Ben-Gurion, Dayan, Peres, and Navon. Gachal (an acronym for “Gush Cheirut Liberalim”) was the party of Menachem Begin, the head of the opposition at the time, which later became the Likud party. Eshkol was being pressured to bring Begin and Dayan into the government. Amazingly, it is clear from the protocols that Begin believed even at the time that he was the person suited to become the prime minister. To his credit, it should be noted that after he became a minister in the government, his suggestions turned out, in retrospect, to be the most intelligent.

Zerach Warhaftig, the Minister of Religious Affairs, was quick to announce that he was prepared to resign from the government in order to allow Begin, Ben-Gurion, or Dayan to join. “Is this a time for petty personal considerations?” he asked.

“What are you suggesting?” Levi Eshkol replied.

Warhaftig, a member of the Mizrachi party who was known for his role in saving the talmidim of the Mir Yeshiva in Shanghai, replied flatly, “I propose inviting Rafi and Gachal into the government. Let Ben-Gurion be the Minister of Defense, and let us invite Gachal to send their best men. If Ben-Gurion doesn’t want to come, then let Dayan come in his place.”

Bentov, a member of the Mapam party and the Minister of Housing, spoke up. “I wouldn’t allow Ben-Gurion to be the Minister of Defense,” he said. “I know him; I have sat with him through two wars.”

Yosef Sapir said, “I don’t know who suggested Dayan. Peres told me, in the name of the Rafi party, that Ben-Gurion should be the prime minister and defense minister, and Eshkol should be his deputy. As a citizen, I would fight to prevent the decisions from being made today by an 81-year-old man.”

Chaim Moshe Shapira, the Minister of the Interior and a member of the Mafdal-Mizrachi party, said, “I beg all of you not to engage in squabbling over power and honor and who will be on top of whom. It is more important for us to be united in the face of what is happening. If we do not overcome the petty drives within us – and all of us have them – then we are bound to suffer as a result.”

Eshkol replied, “The situation right now is that Ben-Gurion and I will not be part of the same government. I will not be together with him in the government. If it is necessary, if it will save the Jewish people, then Eshkol can leave the government, but the two of us will not be together. I simply wouldn’t exist. No one can ask me to become a doormat to anyone. Would anyone who is prepared to leave the government now please raise their hand?”

Chaim Moshe Shapira said, “I am prepared to do that.”

Rabin Warns of Existential Danger

Before the Six Day War, the meetings of the security cabinet were permeated by hysteria. This became clear in a dispute that developed between the army and the government over the question of whether Israel should deliver an immediate death blow to the Egyptian air force, or should accede to the American demand to wait before taking action. At the cabinet session of May 27, 1967, Yitzchok Rabin declared, “If we sit and wait any longer, we will be endangering the security of Israel. It will not be an easy war, but any delay will cause us to pay a much higher price.”

In other words, the country was in danger in either scenario, but waiting would likely be more costly. Nevertheless, the situation was already bad.

“I am not an expert on military affairs,” Yosef Sapir said, “and I don’t even come up to your ankles in that respect, but I understand things that are not military in nature. Today, I spoke with someone who was very emotional about this. This man, who understands these things more than I do, was very fearful; he felt that from a military perspective, we are headed for disaster.” He went on to explain that even if the entire Egyptian air force were to be destroyed, they would arm themselves quickly with new planes. He feared that the battle would lead to the loss of many Israeli pilots and their planes.

It seemed that the country was stuck between the proverbial rock and a hard place. Launching an attack could result in heavy casualties, but the failure to attack would mean the loss of the element of surprise. There was a clear sense that Israel was like a sheep among wolves.

The generals of the army protested, but Levi Eshkol remained resolute. In a cabinet session on June 2, three days before the war, the representatives of the IDF – Yitzchok Rabin, Ariel Sharon, and Matti Peled – sounded militant as they urged the government to authorize an immediate strike.

Rabin, the chief of staff of the IDF, warned, “If you don’t make an immediate decision, there will be serious danger to Israel’s existence. The war will be fierce, it will be difficult, and there will be many losses.”

Sharon added, “All of this hesitation and delaying has cost us our power of deterrence.” He decried the government’s efforts to seek the approval of other countries, which had caused the offensive to be delayed.

Matti Peled, who later became a member of the Knesset on behalf of the party that called itself the Progressive List for Peace, also spoke aggressively. “Why does the IDF doubt its abilities?” he demanded. “What more does an army need to do to win the government’s faith other than winning every battle? We deserve an explanation for this disgrace!”

Levi Eshkol responded to the protesting army officers. “All of our army’s resources are the result of our dealings with other countries. Let us not view ourselves as being such mighty warriors. Without weaponry, we have no power. Even if we weaken the enemy now, they will begin rebuilding tomorrow, and we will also have been weakened by the war. If we have to fight again every ten years, we must think about whether we have an ally who will help us. We will need Johnson in the future; we merely hope that we will not need him in the middle of this battle.”

Matti Peled reacted as if he hadn’t heard a word that Eshkol had said. “We asked for an explanation. Why are we waiting?” he demanded.

“If I haven’t explained that to you yet, then I won’t explain it anymore,” Eshkol said. In other words, if Peled hadn’t understood, then it would be a waste of time to make any more attempts to explain it to him.

Abba Eban Relays

the American Position

The three weeks leading up to the Six Day War were a nerve-wracking period, during which the entire Middle East seemed like a powder keg on the verge of exploding. After months of incidents on Israel’s various borders, Egyptian troops crossed into the Sinai, and Nasser closed the Tiran Straits. With combative proclamations being issued by Israel and the Arab states alike, war had become almost inevitable. The only question was who would actually start the fighting and when.

In Yerushalayim, there was a sense that the Egyptians were ready to go to war. However, it wasn’t absolutely clear, and Israel had no interest in beginning an offensive if the situation was not about to lead to war. That would simply antagonize the Americans. In fact, the motto of the Israeli government seemed to have become: “Let’s not anger the Americans.”

The Egyptians then began moving their troops openly. One week before the war broke out, at 4:00 in the afternoon, the cabinet convened for a tense session. Levi Eshkon gave the government an overview of the military incidents that had occurred on the border with Lebanon, in the vicinity of Yerushalayim, near Chevron, and in other locations. Eshkol reported to the government on the actions taken by the Egyptians, which included a dramatic trip made by the Egyptian chief of staff to coordinate with Syria, which led the latter country to increase its preparedness for war as well. Nevertheless, based on the protocols, Eshkol sounded relatively calm. “One can assume that the Egyptians hope that their actions and their display of strength will deter Israel from carrying out its threats,” he said. “At this point, the order of the Egyptian troops in the Sinai and their general activities indicate that they are building a defensive system. An offensive would require the Egyptians to increase the number of their tanks and to bring additional troops forward in the Sinai. As of now, there are no signs indicating that.”

Eshkol’s sentiments were reinforced by Foreign Minister Abba Eban. “The Americans believe that the movements of the Egyptian army are intended as a display of strength and a gesture of solidarity with Syria, not necessarily for military action,” he said. “There is no question that our warnings have been taken seriously.” In an effort to allay the growing fears that Egypt planned to attack Israel, Abba Eban related that he had been told by the director of the French foreign ministry about a recent conversation between the latter and the president of Egypt. Nasser, the Egyptian president, had spent two hours discussing all the problems in the world with the French diplomat, but, he claimed, the president had not mentioned Israel even once.

Not all of the ministers were convinced. Zalman Aran, the Minister of Education, reminded the cabinet that history shows that when large numbers of troops assemble in a single place, it is invariably a precursor to military action. He demanded to know if the IDF was prepared for that eventuality. Eshkol answered him with a terse “Yes.”

The discussion did not last long. The cabinet members soon moved on to other topics, such as Welfare Minister Yosef Burg’s trip to Poland, the national deficit, and Daylight Savings Time. As far as the government ministers were concerned, war still seemed far away. But the previous two and a half weeks had eroded the usual Israeli optimism. The fact that soldiers on reserve duty had been summoned and were waiting in their bases sowed anxiety among the soldiers themselves and their families, as the Arabs’ threats grew more ominous.

Equating Nasser with Hitler

The days passed, and the Israeli public trembled in fear. Bomb shelters were fixed up in anticipation of the war. Windows were covered with black fabric. Fear hung in the air. Most of the men were called up for reserve duty, and round-the-clock davening and Tehillim was arranged in shuls. At the cabinet session on the evening of June 1, less than four days before the war began, Eshkol came under increasing pressure. He was forced to give in to the public’s demand to establish a national unity government with Menachem Begin’s Gachal party and to surrender the post of Minister of Defense to Moshe Dayan. The protocols reveal that the government ministers praised Eshkol for his courage and wisdom in doing so.

Aside from a dry rundown of events delivered by Yitzchok Rabin, the protocols do not include a direct discussion about the war, either because such a discussion did not take place or because it is still classified. Either way, the prevailing sentiment is clear. Eshkol informed the government ministers of the predictions of the army: The war was not expected to be easy.

Rabin’s comments during that cabinet session give expression to the country’s sense of beleaguerment. “We cannot afford to ignore the proclamations of Nasser and the other Arab leaders that they plan to turn the clock back to before 1948,” he declared. “In simple terms, they intend to destroy the State of Israel! We have told the leaders of the United States, France, Britain, and the Soviet Union that there was once a man named Hitler, and Hitler announced publicly that he planned to destroy the Jews, but the world was silent because they thought he was not serious. For us, the question is how and when to act to ensure that these plans are foiled and that our enemies’ intentions will not be realized. Perhaps it would be better for us to discuss happier things at this cabinet session,” he added, “but it is still difficult to free ourselves from the tension and trepidation that have us in their grip.”

Menachem Begin, who had just joined the government, said, “We are certainly going through difficult times. We all fear what will happen when the moment of truth arrives. There are bound to be many losses in the battle.”

At the cabinet session on Motzoei Shabbos, the decision was made to end the war by terminating the fighting on Israel’s northern border. After Zalman Aran, the Minister of Education and Culture, announced that the war had been “the most legendary war in the history of the Jews, which will give the Jewish people strength for generations,” the ministers stood silently to remember the soldiers who had fallen in battle, and then drank a lechayim to celebrate their victory. Or, perhaps, to celebrate the miracle.

On June 11, 1967, the citizens of the State of Israel woke up to a new reality. Following their dizzying victory over the Arab armies, the size of the young state had suddenly quadrupled, and it had absorbed an Arab populace of about one million people. Now that the fighting had ended, Israel had to develop a position regarding the future of the territories it had captured and of the Palestinians who lived there, in preparation for the UN’s discussion of the subject. Amazingly, every word of the secret discussions at the time reflects the same dilemmas and disputes that are at the center of the political disputes in Israel today. At the end of that cabinet session, Prime Minister Eshkol declared that “we must decide what to do with the Arab residents of the conquered territories.” Apparently, those discussions are still continuing today.

After Shavuos of the year 5727 (on June 14, 1967), the cabinet convened for a five-hour session. It began with an overview of Israel’s diplomatic standing presented by the ambassador to the United Nations, Gidon Rafael. The ambassador announced, “America says that we would help them help us if we keep a lower profile and minimize our discussion about territorial ambitions. Instead, we should speak about our security needs, the freedom of passage in the sea, and the rights that we deserve. That will make it much easier for them to solicit support for us in the United Nations.” Just as it does today, the United Nations created obstacles for us even then.