Mrs. Esther Roth

Each year, the number of Holocaust survivors diminishes, yet every story is precious to record for posterity. This is the personal story of Mrs. Esther Roth, a survivor of Auschwitz, interviewed in her home in Yerushalayim by Menucha Levin.

Esther Roth’s hometown was located in a scenic area called Kaparta-Rus in the Czech Republic, near the Hungarian town of Munkatch.

“My family was very religious and my father served as the local rabbi, chazzan and shochet,” Esther recalls. “There were seven children in our family ranging from the eldest, Chana, a twenty-year-old newlywed, to a four-month-old baby girl. I was the second oldest girl, aged nineteen, when after Pesach, in April 1944, the Nazis invaded our peaceful little village and the nightmare began.”

Esther’s warm, familiar world would never be the same again.

“We tried to persuade our elderly grandfather to cut off his beard, as we’d heard that the Nazis delighted in pulling off Jewish men’s beards. Although at first he was very reluctant to do so, eventually he accepted our advice. My mother went to ask our non-Jewish neighbors for some food, but they refused to give us any. The Nazis forced our family to walk for two days to the Munkatch ghetto. As we walked, I felt panic-stricken, with a strong feeling of foreboding that this was to be the end of our family.

“We arrived there at night, when it was dark. To our great shock, we realized that little seven-year-old Areleh had disappeared. My seventeen-year-old brother went searching for him, and when he found him, we all cried in relief.”

The other children in the ghetto used to pull Areleh’s long peyos, so his parents suggested that they cut them off. Reluctantly, like his grandfather, Areleh agreed to cut his hair.

The family was not given any food for the entire month that they were forced to stay in the ghetto.

“A relative sent us some food packages, but we never saw our mother eat anything,” says Esther. “She tried to feed the baby, but that whole month we never once heard her cry. Perhaps my poor little baby sister was too weak to cry.”

Then came the fateful day when they were all forced into crowded cattle cars and taken to a horrific place called Auschwitz.

When they arrived, some girls who had already been there a while went to welcome the newcomers to the gates of gehennom. These girls looked like living skeletons. Waiting to inspect the new arrivals was the brutal Dr. Josef Mengele ym”sh. Ironically referred to as the “White Angel” by camp inmates, he stood on a platform deciding who would remain alive to work and who would be sent immediately to their deaths.

“My older sister, Chana, and I were quickly separated from our mother and younger siblings, who were taken away to the gas chambers. When I asked the older inmates where they had gone, they pointed to the crematorium’s chimneys,” recalls Esther at the painful memory.

They were unable to accept the cruel reality that their beloved family had vanished into ashes and smoke. They clung to the fragile hope that one day they would still see each other again.

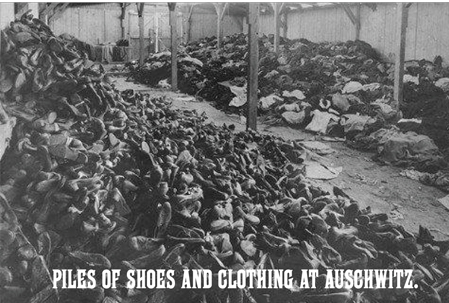

After being tattooed with numbers on their forearms, they were set to work. Their job was to sort through massive piles of belongings taken from Jews on their arrival at Auschwitz. There were huge mounds of clothing, shoes and hats, the earthly possessions of those who no longer had need for them in this world.

“One day, I found a pair of pants that had belonged to my little brother, Areleh,” Esther remembers. “Neatly folded up inside the pocket was his small pair of tzitzis.”

With tears in her eyes, she held this last tangible reminder of her beloved little brother. As much as she longed to keep it, she was aware of the danger involved.

Though allowed to eat any bread and crackers they found, they could not keep any non-edible items. Two girls were foolishly tempted and took some pretty dresses and were immediately sent to the gas chambers.

The crematorium loomed nearby, a constant reminder of impending death.

Frequent selections were conducted when Mengele would stride in, look people over, and decide which ones to send to their doom. As they waited in terrified agony, he would choose his victims at random. Miraculously, both Chana and Esther managed to survive these fearful selections.

In December 1944, after enduring nine long months in Auschwitz, the sisters were sent to Bergen-Belsen, an even more dreadful concentration camp.

“As terrible as Auschwitz was, at least it was relatively clean and we were given some food there. Bergen-Belsen was filthy, full of lice, with minimum nutrition,” Esther said. “There were four girls in the barracks – Chana and I, a distant relative and her friend. Believing it would take a miracle to survive, we vowed that if we did, we would go to Eretz Yisroel. ‘Even if we have to walk there!’ I insisted.

“After an excruciating month in Bergen-Belsen, we were asked if we wanted to go on a transport. All four of us rose as one and immediately volunteered to go. We were disinfected and escaped from the nightmare of Bergen-Belsen. We were taken to work in an ammunition factory, but there at least it was clean.

“However, we were confronted by an extremely cruel Gestapo woman. We heard rumors that she took skin from Jewish children’s bodies to make lampshades. As if to compensate for this woman’s brutality, a kindhearted SS Romanian soldier who spoke Hungarian gave us food.”

One hot April day, the girls were told to walk to a forest. Bright shafts of sunlight poured through the leafy green trees. After the horror and ugliness of the concentration camps, the peaceful serenity of nature reminded them how beautiful the world had once been. Esther realized that it was spring again, exactly one year since they had been forced from their home and beloved family.

Because it was unusually hot during the day, the Nazis made them walk at night. Falling asleep as they walked together, they heard the sound of a waterfall. Though they were permitted to sit down, rain started falling and a cold wind sprang up. They were told not to remain there, as the place was booby-trapped, but some gypsy people did remain behind. The girls had not walked very far when, suddenly, they heard a loud explosion.

“As the earth shook beneath our feet, we realized that we had escaped death just in time. But then it grew even colder and the rain mingled with snow. We shivered and had no food to warm ourselves. Our situation was so unbearable that I told my sister that I did not want to live anymore,” admits Esther. “Chana encouraged me to hold on a little longer. ‘We’ve already survived so much. Please don’t give up now!’ she begged. That was how Chana saved my life.”

Soon they managed to find shelter in a barn. A kind farmer appeared with some hot soup. Huddled in the hay, the girls immediately fell asleep.

The next morning, there was such a thick fog that they could not see each other. In this death march, they had to walk in groups of ten to fifteen girls, five abreast.

“As we walked past a house, I ran inside and saw two loaves of bread on the table. Quickly, I grabbed one and rejoined the march. Later, I wondered why I had not taken both loaves of bread,” says Esther.

Another girl took a blanket and emptied a pot of potatoes she found into it. Discovering some onions growing in a field, they sat down and had an impromptu picnic with the bread, potatoes and onions.

After eating this feast, they were not certain what to do. Bewildered, they simply sat there, staring at each other.

“We realized that we looked like skin and bones, but we did not care. A kindhearted elderly couple found us, gave us food, and allowed us to stay in their barn. By then, the Nazis had all disappeared and we were liberated by the Red Army. The Russian soldiers wanted to shoot the old man, but we begged them not to, since he had provided us with food and shelter.”

At last, the nightmare war they had endured was over.

When the sisters discovered that they were near Prague, they longed to go home. People gave them money for the train and, at first, they went to Bratislava, also known as Pressburg.

Then they went on to Budapest for a few days before returning home to their village in Kaparta-Rus. Since all the bridges had been blown up, the journey took two full weeks.

“We met a cousin who took us home. To our amazement and joy, we discovered that Chana’s husband had also miraculously survived the war together with our father and older brother. Our reunion was unbelievably happy. I always wondered what had happened to my brother during the war, but he found it too painful to discuss. He simply described it as ‘gehennom,’” explains Esther.

“My father had met a religious widower aged twenty-nine who wanted to get remarried and thought I’d be a perfect match for him. However, I was only twenty, and after enduring so much in the war, I wished to complete my education first and not rush into marriage so quickly. My father invited the young man to join us for breakfast one morning, trying to convince me that he was a suitable match. I decided to consult my sister Chana, who was then living in another town.”

When I asked Esther if she had been afraid to travel on her own, since Russian soldiers were everywhere, she firmly maintained, “After Auschwitz, I was not afraid of anything.”

On Esther’s return home, to her shock, she discovered that her engagement party had been arranged in her absence and was taking place that very evening. Her future husband looked more presentable to her then, nicely dressed in a new suit.

“As I loved my father and wanted to please him, I agreed to the marriage. Our engagement lasted only six weeks. Then we were married and lived in Czechoslovakia for a short time. Chana wanted to visit me, but as she was living in Hungary under Russian control, she couldn’t visit. Having survived the war only with Chana’s support, I found it painful to be separated from her by the Iron Curtain,” Esther says with a sigh.

Esther’s husband had a brother who came to Israel in 1948. Life was very difficult then and, sadly, his one-year-old daughter had died from lack of proper nutrition and medical care. He was so bitter that he told them not to move to Israel.

Then Rabbi Schonfield came from London to Prague and met Esther’s husband. He offered him a position in London as a shochet and he immediately accepted it.

“Although London seemed cold and strange at first, I adapted to life there,” Esther explains. “Fortunately, my aptitude for languages enabled me to learn English quickly. I was already fluent in Yiddish, Czech, Hungarian and Russian. My husband and I had three children and we lived in England for twenty-five years.”

When asked how she came to Israel, she explained that her oldest daughter, who currently lives with her, visited Israel and discovered her father’s relatives. She loved Israel, learned Hebrew and met her future husband. After their wedding, they decided to live in Israel.

When their baby girl was born, Esther and her husband visited them. Eventually, when he retired, they made aliyah to Yerushalayim. Esther’s long-ago pledge, made in the horror of Bergen-Belsen, finally came true.

After thanking Esther for the interview, I noticed on the fridge in the kitchen the photographs of five children – two little boys and baby triplets, her great-grandchildren. Due to the strength and courage of this amazing woman, these beautiful children, a new generation, exist in Israel today.