In Parshas Vayakhel, we find an announcement that was never heard before nor repeated in the Torah. The posuk recounts that when Moshe called for donations to the Mishkon, there were so many contributions that a message went out that the campaign was over and the people should stop their donations: “Al ya’asu od melachah leterumas hakodesh, vayikolei ho’om meihovi” (Shemos 36:6).

The Chiddushei Horim wonders why it was necessary to make such a proclamation. Although the donations weren’t needed at that moment, they could certainly have come in handy later on. What would have been so terrible if they would have had extra material and more funds to put to use in the future?

He answers that the Mishkon belonged to Klal Yisroel. Had donations been accepted for the project even though they were no longer necessary, people would have assumed that what they had given didn’t necessarily go for the Mishkon and that their donations went to waste.

No Jew is extra and should never be made to feel as if he is. By ending the campaign when the goal was reached, every contributor knew that he had a share in the Mishkon.

No Jew is superfluous, not then and not now. Every Jew has a share in Torah and fills a necessary role. No matter his social status or degree of wealth, everyone – back then in the dessert and today, as we enjoy a burgeoning population – deserves to be treated as a vital member of our nation.

Even Jews who are not yet religious have a role to play in Yiddishkeit. It is our duty to bring the message of Torah to them and apprise them of the deeper purpose of life that they are missing out on as long as they cling to hedonism and remain estranged from their source.

While in this country, for some reason, the effort to reach and educate unknowledgeable Jews has slowed and fallen from the list of priorities, the kiruv effort in Eretz Yisroel is stronger than ever. Secular Israelis are learning about the faith of their grandparents, and many are seeing the light. I just returned from the holiest city in the world, in the center of a land dotted with programs, yeshivos and study groups established to quench these Jews’ thirst.

I flew to Israel with United Airlines. It’s not the same as flying El Al, where even a non-Zionist like me feels something different about being on a Jewish plane, where all the food is certified kosher and you are guaranteed to find a minyan and people you know.

As I got comfortable in my seat, the first thing I noticed was that the vast majority of the people sitting around me were obviously Israeli Jews. Yet, regrettably, not one of them ordered a kosher meal. It is so upsetting to watch Yidden all around you eating neveilos and treifos.

When you fly El Al, you are spared from seeing that. You arrive in Yerushalayim, stay in Geulah, Shaarei Chesed, Sorotzkin or a kosher hotel, and you can be forgiven for thinking that the entire country is religious. Sadly, that is not the case. And it hurts to come to that realization as you set out on your trip.

However, it is comforting to know that there are organizations, such as Lev L’Achim, Shuvu, Acheinu and many others, that are dedicated to reaching these people and throwing them a lifeline to bring them to an enriched life.

While in Eretz Yisroel, I met with Rabbis Eliezer Sorotzkin and Zvi Schwartz and heard about the latest activities of Lev L’Achim, whose activities continue to grow, reaching an even greater segment of the population and changing the lives of even more people. If they had sufficient funds, they could reach so many more people. There is a feeling that the tide is turning and, in the future, more people who fly United will be ordering kosher meals.

Of course, as hard as we work to increase the levels of kedushah, the Soton seeks to counter with tumah. It is our obligation to remain focused on our goal and not be deterred by what others refer to as “the facts.”

During my visit, I had the distinct pleasure of meeting the Sanzer Rebbe in his home in Kiryat Sanz, Netanya. We discussed various issues, but he was most passionate about the latest volley unleashed by the Reform movement.

While their efforts are well-known to us here in America, in Israel they have not had much influence. We see the spiritual holocaust their movement has caused, with the majority of their adherents virtually lost to the Jewish people. They have basically served as an assimilationist tool, purporting to satisfy the masses with a religious identity as they increasingly move further away from Sinai.

The movement in the US is badly wracked by attrition and increasing loss of membership and support. They and the Conservatives lamely attempt to address their appalling losses by engaging in studies to establish a path to rebranding their product. They bend the laws even more to stay ahead of the progressive curve, and when that fails, they claim to return to tradition, thinking that maybe that will ignite a spark of Jewish identity in the hearts of their adherents after they have lost all apparent interest in their contrivance.

Their leadership perceives this and understands the threat it poses. The recent Pew report pulled away the curtain and showed for all their empty temples and declining membership lists. They come to Israel, where the vast majority of people know one type of Judaism, and that is halachic. While many are not observant, in their hearts burns a connection to their parents, grandparents and traditions.

In Eretz Yisroel, I bought a mezuzah case made of stone and fashioned to be reminiscent of the Kosel. In the airport, I went to the VAT desk for a refund of the taxes paid for that and other gifts I had purchased. The obviously irreligious Sephardic woman who examined the papers and, in Israeli style, stamped everything in triplicate saw that one of the purchased items was a mezuzah.

“Atah medabeir Ivrit?” she asked me. When I answered in the affirmative, she told me her story. Her parents recently passed away and all the children came to their apartment to take what they wanted. She chose to take the various “Birkot Habayit” plaques that were hanging in the house. She hung them up in her apartment facing the front door, and every time she enters her home, she feels the brachot and is blessed.

“Zeh hakotel sheli,” she said. “Tishma, from everything my parents left behind, this is what I wanted. I wanted to have a little piece of brachah, a connection to the world they came from. Atah meivin? This is my connection. Zeh mah sheyeish li. Atah meivin? Do you understand?”

“Kein, kein, ani meivin,” I told her. I assured her that I did, indeed, understand, perhaps even better than her.

She seeks a connection to Yahadus. She wants to be connected to the religion of her parents. Who knows what her children look like? Who knows what her husband looks like? But at least there is hope. There are probably few mitzvos observed in that home, but there is definitely a spark that is kept alive, waiting for someone to come along and ignite it into a flame.

Along comes the Reform movement and tries to establish a beachhead in the Holy Land from which to proclaim to women such as the one who hangs the Birkat Habayit in her home, knowing that she is not entirely loyal to her heritage, that she is a perfect Jew. They call out to her and hundreds of thousands like her and say, “No need to observe mitzvoth. No need to eat kosher. You can live like a goy, with an Arab, and be a better Jew than those chareidim with their long beards and coats and modest clothing and wigs.”

They are in panic mode, so they seek to gain space at the Kosel to show that they are just as good as people who believe in G-d and the Torah. They wish to convince others that people who intermarry are as good as those who are moser nefesh to follow the Shulchan Aruch, our guide of Jewish law and practice.

We can’t let them make the same churban in Israel as they have around the world.

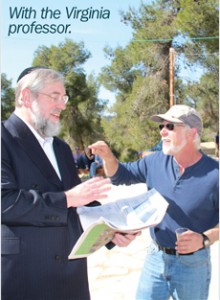

I was reminded of their thinking while visiting a forest dedicated in memory of the three boys who were kidnapped last year and killed in Gush Etzion. I met a professor from a Virginia college who told me that he had spent three weeks in Palestine with his students and was now planning to spend three weeks in Israel.

I told him that there is no such place as Palestine and a debate ensued. I pointed out that there is no such thing as a Palestinian people with an indigenous history and connection to this land. After some back and forth, the professor told me that it is not really important whether the Palestinians are native to the land. “They identify themselves as people whose land this is, and it is our duty to respect that,” he said. He wouldn’t budge from that position, no matter how silly it sounds.

His argument represents the orthodoxy of liberalism as well as Reform. If someone identifies as something, then we have to accept them according to their supposed identity. If a person self-identifies as a major league baseball player, I asked the professor, are we obligated to accept him as such? He seemed stumped. Apparently, in academia, they hadn’t discussed that one yet.

I felt an obligation to try to get through to him and plant some seeds of doubt in his mind. Maybe he will be honest enough to think about it and realize the falsity of his arguments and Palestinian claims.

The discussion gave me a new understanding of the Reform position. They don’t observe any of the commandments at all. Many of them or their children are not even Jewish, but they say that if they identify as Jews, then they are Jews.

We don’t have to accept their fiction. We have to do what we can to prove what they are all about. We have to be a step ahead of them as they prepare their assault on Yerushalayim and all of Israel. Only the truth will enliven their neshamot and bring them the inner peace and satisfaction their forefathers enjoyed.

Rav Yankel Galinsky recalled arriving at the home of the Chazon Ish, the nerve center of Torah Jewry, after a long day of trying to rescue Jewish children. He was disheartened from the seemingly successful efforts of the secular Zionist leadership, who were determined to snatch every Jewish soul arriving in Israel and prevent it from being exposed to a Torah education. He told the Chazon Ish of his inability to pierce the Zionist fence and reach those children.

The Chazon Ish listened and then smiled. “Reb Yankev,” he said softly, “mir velen gevinen.” Three words. We will triumph.

Those three words were enough to keep Rav Galinsky and his fellow forerunners of P’eylim/Lev L’Achim at work. Those words fueled daring, spirited campaigns that succeeded in saving many children.

Were we to appreciate the inherent value and goodness in each neshomah, we would enthusiastically join the battle, knowing that the truth will emerge victorious.

If we appreciate the value of every Jew, we would never treat others in our world as if they are superfluous, unneeded and expendable.

During my trip, I was further reminded of the beauty of each neshomah and exposed to the “nitzotz kedushah” of every Jew as I waited for a taxi with the sun beating down on me, “kechom hayom.” I stood on a corner in a neighborhood I had never visited before and waited in vain for a taxi to drive by.

There is no better place to be reminded of the beauty of Jews than in Yerushalayim, and quite often it is a taxi driver who delivers that reminder.

The protagonist of my story was rolling slowly down the hill, when I stuck out my hand to signal for him to stop. The driver of a gleaming new car stopped next to me and asked me to enter. I saw that there was a woman sitting in the back and asked her if she was okay with me intruding. I then sat down.

The driver was smiling broadly as he welcomed me to his car.

“Ha’Elokim shalach oti eilecha,” my kippa-less driver laughed heartily.

He was taking the woman to an office on a different street, but he had made a wrong turn and ended up on the street where I stood.

With typical taxi-driver bravado, he told me, “Never before have I made a wrong turn. I never get lost. So if I’m on this street, I’m clearly not lost. Clearly, ha’Elokim shalach oti lepo lakachat otcha. Hashem sent me here to pick you up.”

After he dropped off the woman, he explained the reason for his happiness. The car was brand new; I was the fourth person to sit in it. It was a fancy vehicle and his wife was annoyed with him that he spent so much money on the car he sat in all day.

“Atah ro’eh? See how Hashem is looking out for me. I was thinking that maybe she is right. But now I see once again how ha’Elokim ozer li. He sent me here to pick you up while I still had another passenger in the car. Ha’Elokim wants to show me how He provides for me. He made me get lost in order to find you and be reminded that everything comes from Him.

“Ha’Elokim shalach oti eilecha to remind me that every passenger I get is from Him and that He is always looking out for me and helping me.

“He sent me on a mission to pick up a Jew to teach me that lesson.”

I climbed out of the new car filled with a deep sense of ahavas Yisroel and an appreciation for the people whose neshamos carry that spark.

It will take some convincing to persuade a person like him, who sees Hashem everywhere, that it’s enough to identify as a Jew. He knows the truth. He knows you can’t be a Yehudi without acknowledging Hashem and performing the mitzvot.

He and people like him live with the knowledge that ha’Elokim shalach otanu. We all have a distinct mission, and any wrong turns we make are really right. They are all Divinely orchestrated.

The taxi driver was merely echoing an age-old phrase.

As Yosef’s brothers wept when he revealed his identity to them, he told them, “Lo atem shalachtem osi, it is not you who sent me to Mitzrayim, ki ha’Elokim. It was all Hashem’s plan” (Bereishis 45:8)

Mordechai Hatzaddik told Esther, “Umi yodeia, who knows, if perhaps the reason you were chosen as queen was Divinely ordained so that you will be able to appeal to Achashveirosh to save your brothers and sisters” (Esther 4:14).

Chazal state that not only are the luchos kept in the Aron, as the posuk prescribes, but the shivrei luchos are kept there as well (Bava Basra 14b). Not only the extant luchos, the holy repositories of the devar Hashem, are kept in the Kodesh Hakodoshim, but also the broken shards, which represent splinters of dashed hopes, are kept in the Aron. They, too, are holy.

We live in a generation of shivrei luchos. All of us carry those sparks of brokenness. Our task is to uncover the sparks of holiness and cause them to ignite. While the anti-halachic movements march on with their cynical agendas of covering up the kedushah, denying its existence and smothering its sparks, our assignment is to take the shivrei luchos and combine them with the luchos so that they may become full and holy.

We need not fear them and their power. With pride and knowledge, we can combat them.

I visited Rav Chaim Kanievsky last Thursday night and posed some questions. He looked at me and said, “Host peyos? Do you have peyos?” I answered in the affirmative. He said, “Nem zei arois. Remove them from behind your ears and put them in front.”

When I did as he asked, a broad smile spread across his face as he said to me, “Du host azelecha sheine peyos. Far vos bahalst du zei? Foon vemen shemt ihr? You have such nice peyos. Why do you hide them? From whom are you embarrassed?

“Di goyim?

“Darfst nit shemen.”

We must remember that we have nothing to be ashamed of. We have no one to be ashamed of.

We have the truth. We observe the mitzvos as our parents and grandparents did, going back to Kabbolas HaTorah.

We need to be proud of our heritage, proud of what we are able to accomplish. Our failures can also be holy. We need to learn from them and know that whatever happens, ha’Elokim shalach oti. Hashem sent us here with a mission.

Let’s do our best to complete that mission properly, with pride.

It can be done.

Mir velen givenen.