The Cornflakes Calamity

We have always envied the Swiss for living in a quiet country. In Switzerland, the front page stories in the newspapers generally focus on ecological issues. Iin the worst case scenario, the newspapers may report on a bridge somewhere that has developed a fault. We have always yearned for the day when the top news stories in Israel will be about a leopard that was born in a zoo or the inauguration of a new airport. Well, now it is finally happening, albeit not exactly as we imagined it.

Believe it or not, every front page story over the past ten days or so has dealt with a single topic: cornflakes. That’s right. The Israeli media has been focusing almost exclusively on a breakfast cereal. And why is that? Well, the reason isn’t quite as prosaic as in Switzerland. In Telma, the Israeli company that manufactures cornflakes, it was discovered that a portion of the company’s products were infected with salmonella. And with that, pure bedlam descended upon the country.

This is not an ecological issue. It is a health issue. Salmonella is dangerous. The clinical symptoms of infection are diarrhea, stomach pains and cramps, high fever, headaches, nausea and vomiting. The bacteria can also cause severe damage to the digestive system.

Now, what is the reason for this intense focus on the story? First of all, today there is a heightened awareness of all sorts of issues concerning food and bacteria. Second, the infected product is one that is used in almost every Israeli home, and the news of the contamination led to a major uproar. Ever since the news first came to light, the sales of Telma products have plummeted almost to zero. But the situation continued to snowball even after that.

First, the company announced that the reports were untrue. Then it admitted that there had been some contamination, but it claimed that the affected products had remained in the factory and hadn’t been marketed at all. The final confession – as of now – came when Telma admitted that a few contaminated products had indeed been sold. The tainted products, the company insists, were sold completely inadvertently.

As of now, there are demands for the management of the factory to be fired. After a few days of public indignation, the Unilever company, which manufactures Telma’s cornflakes, announced that it had found the person at fault: A worker had changed the stickers on an entire run of the product that had been barred from distribution. Then there is someone to blame, after all: the very employee who was supposed to be protecting consumers.

Meanwhile, a second, similar scandal has erupted. This time, it concerns the salads manufactured by the Shamir company. Apparently, the company that manufactures techinah and supplies it to Shamir is the source of the problem, but in any event, the same bacteria have been detected in Shamir’s salads.

Cereal Liars

The Telma cornflakes scandal erupted on Thursday two weeks ago. At the time, senior company officials tried to allay the public’s fears, but it turned out that they were deceiving the public instead. On Sunday, the company published notices of apology in the newspapers. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health is considering suspending Telma’s manufacturing license. Yaakov Litzman, the Minister of Health, announced, “If we find that they lied to us, I will not hesitate to take drastic steps against the company.” Litzman has already appointed an investigative team to visit the factory.

This fiasco may turn out to be damaging for Litzman himself, both because he was the minister responsible for supervising the company’s health standards, and because he played a part in reassuring the public, when news of the contamination first came to light, that there was nothing to fear. As it turned out, he was mistaken.

Litzman may not be certain if the company lied to him, but I am certain that they did. Allow me to explain.

On the last day that the Knesset was in session – on Wednesday, two weeks ago – MK Yitzchok Vaknin submitted an urgent parliamentary query with the following text: “The media has been reporting that some consumers may have purchased cornflakes manufactured by Telma that were contaminated with salmonella. The company announced that no contaminated products were sold, but it also agreed to allow the products to be returned for a refund. The Ministry of Health has yet to make a statement on the subject. I would like to know if the issue is being investigated, and if so, would you give some clear information to the public?” It should be noted that when this question was asked, it was still not known that the company had lied and contaminated products had indeed been sold.

Litzman was vehement in his response. “An inspection at the factory conducted by the Food Service of the Ministry of Health revealed that after the company’s independent review of the products manufactured between June 23 and June 30 on production line B, those products were withheld from the market and were placed in quarantine in the company’s warehouses and slated for destruction. The products that were not marketed were the company’s Cornflakes of Champions under the Badatz, sold in 750-gram boxes, and the 750-gram boxes of Kokoman Shells marked ‘B.’ Upon inspection, other batches of the products from other lines were found to be unaffected. In light of the fact that the products were not placed on the market, and were instead quarantined by the company, there was no need for the public to be warned. The Food Service is continuing to monitor the situation and will oversee the destruction of the contaminated items.”

Thus, Litzman avowed in the Knesset that the contaminated cereals had been blocked from the market. Two days later, though, it was revealed that some of the cereals had indeed been sold. Not only did the company lie to him and to the Ministry of Health, they also caused him to make a false statement in the Knesset. It was an innocent mistake on his part, but it was false nonetheless.

Another member of the Knesset, Haj-Yihye, asked another question: “We still haven’t heard what happened to the contaminated batch. Were the cornflakes destroyed? What happened to them? Even if we know they haven’t been placed on the market yet, can anyone guarantee us that they won’t end up being sold? Someone needs to make sure that the quantity that has already been produced on that line will be destroyed.”

Once again, Litzman tried to reassure his questioner that there was no reason for concern. “The answer is essentially the same to both questioners,” he said. “First of all, there was no actual problem; the company caught the contamination before the products had left the factory, and they remained there. There was no reason to create a stir; mistakes happen with all sorts of products. As long as the cornflakes weren’t released, there was no reason to alarm the public. Nothing happened.”

Haj-Yihye tried to speak up again, but Litzman interrupted him. “Wait a minute. You didn’t hear my answer to the previous question. I have already said that the Ministry of Health will oversee the destruction of the contaminated cereals. We are going to make sure that they are all destroyed. That is the answer to your question as well. But I will add, without any connection to what I have already said, that I am looking into the possibility of obligating every company to report situations such as this one. To date, there is no requirement for a company to report contaminations as long as the product hasn’t left its facilities. If it does, I am required to report to you, but if it is an internal matter, and the company itself handles the situation and takes the requisite steps, it is all right.”

A Tax on Three Apartments

Moshe Kachlon, the Minister of Finance, ran for office with a promise to look out for the weaker sectors of society. That promise is now being put to the test. In the upcoming discussions over the national budget, Kachlon’s constituents will watch to see whether the budget will bring good news for the disadvantaged.

As of now, Kachlon does not seem to be favored in the polls. The voters have already been disappointed by his performance in addressing Israel’s housing issues, and if the new budget does not show a significant socialist influence, it will likely lead to an even greater drop in his popularity. Last year, Kachlon announced from the Knesset podium that the state budget would be the most beneficial in Israel’s history for the poor. The question now is whether that still holds true.

The discussions will begin over the course of the next two weeks. The Knesset will convene for a special debate despite the summer recess, and the state budget will be approved following its first reading. The budget will then be sent to the Knesset Finance Committee for more detailed discussion. Ostensibly, the government should have no problem getting the budget approved, since it has a majority both in the plenum and on all the committees.

Nevertheless, there is always the possibility that a few Knesset members of the coalition – and all it takes is one or two to create a problem – will decide that their consciences do not allow them to vote with the government on some issue. If that happens, then there will certainly be fireworks; it has happened in the past as well. It is already clear that the Knesset will not accept the move to make sweeping budget cuts to all the government ministries. Some of those proposed cuts would cause direct harm to the elderly or the infirm.

In the meantime, Kachlon has announced one new tax that he intends to enact in order to generate funds to benefit the weaker sectors: a tax on owners of three or more apartments. This has some bearing on the chareidi community, where a trend has developed for families to use their investment money to purchase additional apartments in cities on the periphery of the country. For the price of half an apartment in Yerushalayim or Bnei Brak, a person can purchase two apartments in Kiryat Gat or Dimona. The apartments can be rented to students or to young chiloni couples, and the investor can thus regain his money after a few years. Aside from that, he will own a piece of property that can be sold at a profit when the time is right. These property owners are not the targets of the finance minister’s proposed legislation, which is actually aimed at real estate moguls. Nevertheless, Moshe Gafni, the head of the Knesset Finance Committee, has already announced that his committee will never allow the proposed tax to pass. Naturally, Gafni’s interest is in protecting yungeleit.

This tax may also affect families who live in America and who have purchased several apartments in Israel. Moreover, it was recently reported that there are quite a number of Knesset members who will personally suffer from the tax, since they themselves own a number of apartments. Will they vote against the tax because of their personal interests? Perhaps, since the law does not prohibit them from doing so.

Meanwhile, the labor strikes in response to the budget are already beginning. The country’s local authorities have already announced that if their budgets are cut, they will prevent the new school year from beginning as scheduled on September 1. There are threats every year that the beginning of the school year will be delayed, but it is usually due to a dispute over teachers’ wages. This time, the threat comes from the municipal authorities themselves. A doctors’ strike has also been threatened, both because of the low pay for medical professionals and because of the reform to the medical system that the health minister plans to institute.

Terror Does Not Rest

In the past, I have often reported to you about the rampant acts of terror. The terror attacks have decreased lately. If you would like to know why, then you should read the interview that I will be publishing here in a week or two with MK Yitzchok Vaknin, who serves as the head of the Knesset Ethics Committee. Vaknin claims that since the Ethics Committee prohibited the Arab members of the Knesset – and any other Knesset members, in fact – to visit the Har Habayis, the immediate result has been a reduction in terror attacks. There is some logic to that.

Nevertheless, there have still been occasional attempts to murder Jews. Boruch Hashem, they have been unsuccessful. One such attempt took place this past week at the Me’oras Hamachpeilah, where a female terrorist drew a knife and lunged toward a group of soldiers. The soldiers subdued her with tear gas and arrested her. Miraculously, there was no loss of life. Last Thursday, a chassidishe bochur was stabbed while making his way to visit the tziyun of the Nesivos Shalom of Slonim on Har Hazeisim. An Arab stabbed the young man with a screwdriver and then fled the scene. Add this to the attack that took place last month, when a terrorist stabbed two soldiers on Route 60, the highway that connects Gush Etzion to Chevron. In short, it should not be said that there have been no attempted terror attacks at all. The attempts have been made, but with Hashem’s help, they have not been successful.

Another subject that I have discussed frequently in these pages is the efforts of the Reform movement to promote their agenda in Israel. Those efforts, too, are continuing, and I plan to write more about that subject next week, bli neder.

Criminals at the Kever of Rav Shimon bar Yochai

Everyone is familiar with pashkevilim, the large notices pasted on walls and message boards on the streets of Israel’s chareidi neighborhoods. When an anonymous pashkevil is posted against someone, it is not only an aveirah; it also loses its influence altogether. This is all the more true if the language of the notice is combative, insulting, or inflammatory. In effect, this means that a pashkevil actually works against the person who writes it and benefits its intended target. Perhaps this is even a deliberate tactic: A person who feels the need to enhance his standing can do so simply by asking someone to put out a viciously worded pashkevil against him.

Why do I mention this? Because just this week, an incendiary letter was published against Rav Shmuel Rabinovich, the rov of the Kosel and other mekomos kedoshim. The authors of the pashkevil accused the rov of harassing innocent visitors to Meron. The rov’s detractors went so far as to call him by his last name alone, without using his rabbinic title. It was as if he was not a public servant, and the defender of Klal Yisroel’s sacred sites. To them, he was merely “Rabinovich” and nothing else. Yet we know – as I noted in these pages last week – that a group of thugs and criminals decided to seek shelter in Meron. After all, there is plenty of food there, as well as places to sleep. Some of those vagrants are convicted felons who were released from prison and have nowhere else to go.

Rather than tarnish Rav Rabinovich’s good name, the letter seems merely to have called attention to his noble actions. It is clear that Rav Rabinovich did exactly what was necessary, at a time when remaining silent was not an option.

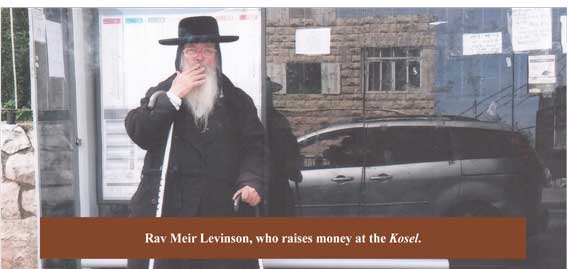

But this leads us to a similar subject: the issue of the tzedakah collectors at the Kosel and the efforts being made to remove them. One of those collectors, Rav Meir Levinson, is someone I know personally. Rav Meir lives in Givat Shaul and is not only a kindhearted baal chessed but also an outstanding talmid chochom. He always has a vort to share, he is well-versed in Medrashim, and he can quote a teaching of any chassidishe luminary you choose. Rav Meir himself is a chossid of both Breslov and Chabad. A tzedakah collector like Rav Meir should be viewed as a precious gem, yet efforts are being made to remove him from the Kosel, and the police have harassed him on several occasions.

Unlike in the case of the thugs in Meron, Rav Shmuel Rabinovich is not responsible for the events at the Kosel, as you will see from the fascinating exchange of letters quoted below.

The Taxi Driver’s Tishah B’Av

Tishah B’Av is now behind us. I don’t know what the aveilus is like for you in Monticello and Woodbourne, or in Baltimore and Miami, but here in Yerushalayim we feel it very keenly. We are burdened by the knowledge of Chazal’s teaching that any generation that does not experience the rebuilding of the Bais Hamikdosh is viewed as if it is responsible for its destruction. We live in proximity to the Kosel, a poignant reminder of what we have lost. Once again, Tishah B’Av was a day of tears. Once again, we ended the day with the hope that our Kinnos will no longer be needed next year, and that we will be able to greet Moshiach and see the Bais Hamikdosh rebuilt.

Let me share a story with you. Rav Zilberman once remarked that a person must always seek ways to give others the benefit of the doubt, even for a simple taxi driver who plays backgammon on Tishah B’Av. This is the story he told:

“I was once traveling in a taxi on Erev Tishah B’Av, and the driver and I began discussing the churban and the aveilus of Tishah B’Av. In the middle of our conversation, he let out a sigh and remarked that he was unable to fast on Tishah B’Av, and that he was capable of fasting only on Yom Kippur.

“When I heard this,” Rav Zilberman continued, “I felt sad. I didn’t know what to say. But the driver continued, ‘Tonight, I will be getting together with a few of the other drivers from the station, and we will play backgammon until the morning.’

“That was already too much for me,” Rav Zilberman sighed. “To spend the night of Tishah B’Av playing backgammon? How could they do such a thing? But then the driver concluded, ‘You see, we aren’t able to fast, but we want to fast, so we play backgammon all night long and then we go to the Kosel at sunrise for Kinnos and Shacharis, and we go to sleep until the end of the fast….”

I will conclude with a brief quote from Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, which is relevant not only to Tishah B’Av but to the rest of the year as well: “Even though our generation has improved and there are many people who are meticulous about halachah, and who take care to learn the Word of Hashem regarding every step of their lives, one must still take care not to give secondary matters priority over the things that are more important. Sometimes, with all the care that is invested in learning the details of the minhagim that awaken mourning over the churban, we forget to contemplate the main obligation of these days, which is to grieve over the churban and to examine our deeds, to repent before Hashem and to yearn for His salvation.”

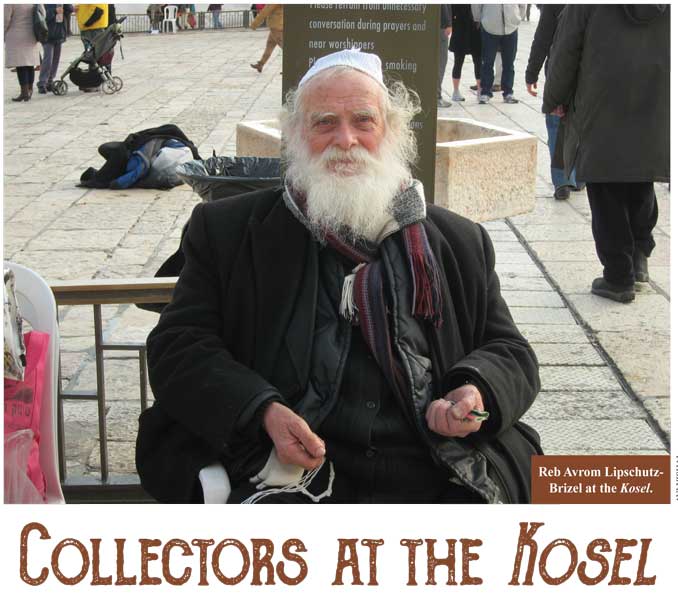

Collectors at the Kosel

Rav Shmuel Rabinovich recently penned the following letter to Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein, the rov of Ramat Elchonon: “At the Kosel there are tzedakah boxes, and one third of the money collected there is distributed every year for Pesach to organizations such as Yad Eliezer. The other two-thirds are used for the upkeep and renovation of the site. According to the law established many years ago, it is prohibited to collect tzedakah at the Kosel, except in the designated boxes and at specific times such as Erev Rosh Hashanah and Erev Yom Kippur. The police enforce this law at times and ignore it at times, as they see fit. The question is what I should do on this subject, or if it would be preferable for me to do nothing at all.” Rav Rabinovich emphasized the potential for chillul Hashem, particularly in the eyes of secular visitors to the Kosel and of those who are paying their first visit to the site.

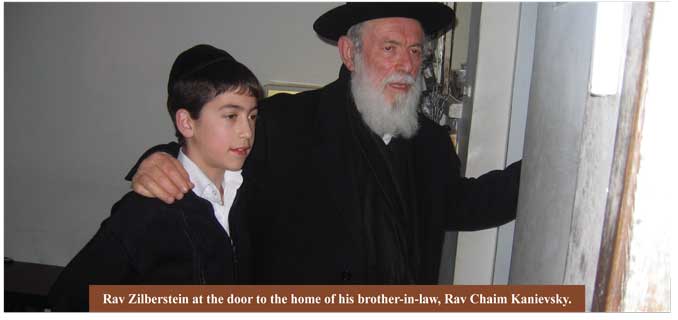

In his response, Rav Zilberstein revealed that he relayed the question to his brother-in-law, Rav Chaim Kanievsky, adding that “he was horrified by the very idea of prohibiting the poor from collecting tzedakah!” The reason, he explained, is that “Yerushalayim will be redeemed only through tzedakah. Moreover, how can anyone withhold the merit of giving tzedakah in a place such as this?” Rav Chaim’s p’sak was unequivocal.

“I also told my brother-in-law shlit”a,” Rav Zilberstein continued, “that there is not a single day that goes by without non-Jews visiting the Kosel, in fulfillment of the posuk that states, ‘For My House will be called a house of prayer for all the nations.’ I told him that when I once visited the Kosel on a day when there was snow and there were hardly any Jews there, I saw a group of non-Jews who had come to pray. I once heard a priest who came from Greece praying, ‘G-d, save the Greek economy.’ Since that is the case, I suggested that when poor people come to ask these non-Jews for tzedakah, it may be a chillul Hashem, for it is forbidden to ask for tzedakah from a non-Jew. My brother-in-law shlit”a agreed to that, and he said that if a person sees a pauper approaching a non-Jew to ask for tzedakah, he should admonish him to stop. If he does not listen, he may be removed from there.” Rav Zilberstein added that a person who brazenly demands tzedakah may be suspected of not being truly needy. “But in general,” he concluded, “aside from those two examples, it is not a Jewish custom to prohibit the poor from collecting tzedakah, especially at the Kosel Hamaarovi, where we particularly need the merit of tzedakah in order to bring the geulah.”

The correspondence did not end there. Rav Rabinovich quickly responded with a second letter, explaining the situation in greater detail. “The law against collecting money has existed for many years,” he explained, “since before I was appointed as the rov of the Kosel Hamaaravi; it was prompted by the disturbances caused by disruptive collectors. In general, the police enforce the law only against those who are disruptive. (Their orders are to stop only the disruptive collectors, but they sometimes do not assess a situation accurately.) Unfortunately, most of the collectors ask non-Jewish visitors as well for tzedakah. Since my staff and I cannot oversee every individual action, the question is if I should insist that the area be open for collectors despite the chillul Hashem, or if I should make a clear statement that the police should act only against the collectors who are disruptive, and then I should be passive on the subject.”

Rav Zilberstein’s response was fascinating. It was evident that he sympathized with the righteous among the tzedakah collectors. “If what you say is true,” he wrote, “and most of the collectors are asking for donations from non-Jews, then they should be told not to do that, and if they do so, they should be distanced from the area. The same is true of those who do not conduct themselves with derech eretz for the holy site and who cause a chillul Hashem. They should be admonished to behave in an appropriate manner for the House of Hashem, and if they do not listen, they should be driven away. Now, you claim that you are not responsible for this, yet you can give directives to the authorities regarding how to handle this matter. Therefore, it is proper for you to make a polite request of the police and to explain to them that chesed is one of the pillars of the world, and that it is unimaginable that there should not be chesed at this holy site. Nevertheless, anyone who causes a chillul Hashem should be sent away.”

As for Rav Meir Levinson, the tzedakah collector who has earned my deepest respect, he and the others like him were not the subjects of the correspondence cited above. Their approach is the exact opposite of the insolence opposed by Rav Zilberstein and Rav Chaim, and they know exactly whom to approach for tzedakah and how. In fact, many visitors to the Kosel are attracted by their pleasant demeanors and approach them on their own accord. It would indeed be appropriate for the police to be asked to let them continue their collecting undisturbed. And while it may be appropriate indeed to drive away the more brazen collectors at the Kosel, I would not want to be the one to make that decision.