Dear Editor,

Your article on the 100th anniversary of OU Kosher supervision services brought back many vivid memories of my experiences growing up in a kosher home in a mid-sized “out-of-town” Jewish community during the 1950s and early 1960s.

As a teenager, I felt a sense of eager anticipation each time I went food shopping with my parents at the supermarkets in Miami Beach, Florida, wondering which of the formerly treife products on their shelves had newly become available to us because of the OU symbol that suddenly appeared on their labels.

After arriving in New York City in 1964 to go to college and learn in yeshiva, I spent a lot of time at the Orthodox Union’s national offices during the next 16 years, first as a volunteer for the OU’s NCSY youth kiruv organization, and eventually as a paid member of the Orthodox Union’s professional staff.

As the director of publications and public relations, my duties included producing and distributing a quarter of a million copies of the annual OU Kosher for Passover Products Directory. That gave me the rare privilege and opportunity to meet and work with the dedicated rabbis and Orthodox Union lay leaders of that era, whose groundbreaking efforts vastly expanded the universe of reliably kosher food products, while elevating kashrus standards nationwide and, eventually, around the world.

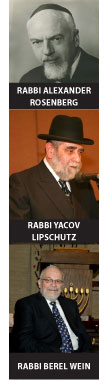

Rabbi Alexander S. Rosenberg was appointed the rabbinic administrator of the OU Kashrus Division in 1951. The division was established in 1923 to put an end to the notorious corruption and chaos that hobbled kashrus supervision in the United States during the previous three decades. But as popular Jewish historian Rabbi Berel Wein wrote in a 2002 article published by the OU’s Jewish Action magazine, “it was not until Rabbi Alexander Rosenberg became the rabbinic kashrus administrator of the OU that real progress was made. Rabbi Rosenberg, descended from a distinguished family of Hungarian rabbis, combined within himself old-world charm, a shrewd understanding of people and their motives, an uncanny business sense, unimpeachable integrity, enormous compassion, and a sense of public service that allowed him to see the big picture.”

As Rabbi Wein wrote, in addition to his credentials “as an accomplished talmid chochom,” Rabbi Rosenberg’s “aristocratic manner, his handsome appearance and immaculate dress” made an indelible impression on everyone he met, Jew and non-Jew alike, and established him as the foremost authority and advocate for kashrus of that era.

The power of Rabbi Rosenberg’s Torah personality enabled him to expand the scope of the OU’s kashrus supervision service beyond those “niche” food companies that had always catered primarily to the kosher consumer and broaden the OU’s presence in the mainstream national food market.

“It was Rabbi Rosenberg,” Rabbi Wein wrote, “who impressed upon major American food companies such as Colgate-Palmolive, H.J. Heinz, Rich’s, Procter & Gamble, Best Foods and others the possibilities for them in kosher production and supervision.”

Over the next 22 years, Rabbi Rosenberg worked closely with his longtime field assistant at the OU, Rabbi Yacov Lipschutz, and the managers of the food plants under OU supervision. Together, they developed innovative and effective solutions to the myriad problems that arose in applying the OU’s rigorous kashrus standards to the rapid advances then being made in food production technology.

During that period, the OU’s kashrus operations were largely protected from internal organizational and economic pressures by Mr. Nathan K. Gross, the longtime lay chairman of the OU’s non-halachic policymaking Joint Kashrus Commission. Under Gross’ independent leadership, the OU deliberately undertook some supervisions at a substantial financial loss in an effort to meet the larger needs of the Orthodox community, and to introduce higher halachic standards for the entire kosher marketplace than some of those in widespread use at the time.

The techniques and procedures that Rabbi Rosenberg and Rabbi Lipschutz invented have become standard practice throughout the kashrus world. Their application to the countless thousands of raw ingredients that are used in kosher food production on an industrial scale has made possible the explosive growth of the worldwide kosher food industry over the past fifty years.

Rabbi Lipschutz resigned from the OU in 1980, and Rabbi Menachem Genack was selected to take over from him and was named the OU Kashrus Division’s chief executive officer. But Rabbi Lipschutz still maintained his reputation as one of the world’s foremost authorities on modern kosher food production and supervision. I was privileged to work with him on the early drafts of his book titled “Kashruth,” which was published by ArtScroll in 1988. It remains to this day one of the most comprehensive guides to the principles of kashrus written for the layman, covering the most commonly used food ingredients and additives, and including a complete list of kosher and non-kosher fish species.

Rabbi Rosenberg’s unassailable reputation for personal integrity, and his insistence on upholding the highest possible halachic

standards for the OU’s hashgocha, made him immune to the economic and political pressures that had fatally compromised so many private and local community kashrua hashgachos over the previous 60 years, and enabled him to firmly establish the OU symbol on a product label as America’s gold standard for kashrus quality and reliability.

However, Rabbi Wein wrote, Rabbi Rosenberg’s “greatest accomplishment was that wherever he went and with whomever he dealt, the experience always turned into a kiddush Hashem.” Rabbi Wein often told the following story to illustrate that point.

In 1974, the Arab states declared a boycott on oil exports to the U.S. and its allies in retaliation for their support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War the previous year. The resulting shortage of oil forced one of the two main suppliers of kosher glycerin in the United States, both of which were under OU supervision, to suspend its deliveries to its clients.

When Rabbi Rosenberg passed away in 1972, the officers of the Orthodox Union asked Rabbi Wein, who had only recently come to New York City to serve as the OU’s executive vice president, to take over as the OU Kashrus Division’s rabbinic administrator, and Rabbi Wein agreed. In 1974, serving in that capacity, Rabbi Wein received a phone call from a senior executive at an OU-supervised food company who was in a panic because his firm was fast running out of kosher glycerin and would have to shut down production, at a huge financial loss, if it could not quickly locate a new supply.

Rabbi Wein agreed to help and placed a phone call to a vice president at the second company that was still producing kosher glycerin under OU supervision. He explained the situation and then asked for a favor. Would the second supplier of kosher glycerin be willing to deliver several tank cars of the ingredient, on an emergency basis, to the company that had run out, even though it was not a regular customer?

It was not a simple request. Because of the oil embargo, the spot market price for the limited amount of kosher glycerin still available was sky high. After thinking for a moment, the non-Jewish vice president responded by asking the following question, “Rabbi, do you think Rabbi Rosenberg in heaven knows what I am doing for you?” After Rabbi Wein answered “yes,” the non-Jewish vice president told him that his company would make the requested delivery of kosher glycerin to the OU-supervised food company and charge it at the much lower contract price usually reserved for its regular, long term customers.

Under the leadership of Rabbi Genack, Rabbi Elefant and many other dedicated members of the Orthodox Union’s staff, as well as its lay leadership, the OU Kashrus Division has become a much larger and more efficient operation than it was during those years. But as Sir Isaac Newton said in a letter to fellow British scientist Robert Hooke in 1675, their success was due to the fact that they were “standing on the shoulders of giants” who came before them.

Today, as kosher consumers, we, too, have an obligation to recognize and honor the memory of those kashrus giants of the past who laid the firm foundation for the OU’s many accomplishments over the past century, from which we all benefit.

Yehi zichrom boruch.