Shortly after the decision was announced, Mr. Gershon Schlesinger, Executive Board Chairman of UJCare in Williamsburg, said the community was pleased with the decision.

Mr. Schlesinger said, “The lawsuit didn’t make sense from the beginning. Why are hotels and fine dining establishments allowed to have dress codes for their patrons without any issues? It was a clear double standard.”

Now that the issue has been successfully resolved, let’s take an in-depth look at the case, which was brought by the New York City Commission on Human Rights.

– – – –

The very busy Commission has a full caseload of abuses to prosecute, coupled with a hefty treasury with which to promote their agenda.

The Commission, which is dedicated, according to their website, to “the enforcement of the Human Rights Law, Title 8 of the Administrative Code of the City of New York, and with educating the public and encouraging positive community relations,” had found a new whipping boy: a couple of community shops located on Lee Avenue in Williamsburg. These include Tiv-Tov Stores, Inc., Achim Management Llc, Gestetner Printing, Sander’s Bakery, and others.

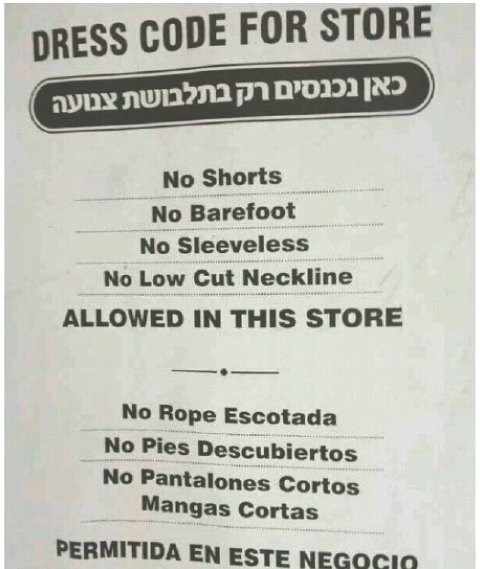

Their crime? Posting ‘modesty signs,’ asking customers to refrain from wearing shorts, going barefoot, or shopping with sleeveless attire, in their stores.

Back in February 2013, seven stores were notified by the Human Rights Commission, (which is charged with protecting the rights of both citizens and shopkeepers), that they would be sued over the signs. The Commission claimed that the modesty signs singled out a certain segment of the population.

According to the formal document, “The complaint alleges that the signs discriminated on the basis of gender and creed in violation of section 8-107(4)(a) of the Administrative Code Petitioner likewise asserts that there are no material issues of fact regarding the gender discrimination claim. It argues that “words like ‘sleeveless’ and ‘low-cut neckline’ are, on their face, a reference to women’s dress” (Pet. Mot. at 7). In support of this assertion, petitioner cites a portion of a definition of “low-cut neckline” from the 1913 version of Webster’s Unabridged

Dictionary. Accordingly, petitioner concludes the signs are intended for women, not men.”

“There’s nothing wrong with a dress code,” explained Clifford Mulqueen, the Deputy Commissioner and General Counsel for the Commission on Human Rights. “What the law says is that you can’t advertise in a way that might make one protected group of individuals uncomfortable. When you speak about sleeveless shirts or low-cut necklines you’re specifically referring to women’s dress, and that may make women feel unconformable and unwelcome.”

The business owners, who were bewildered by the summons, immediately removed the signs. They protested that they had never made any customer feel unwelcome, and that the signs were not referring to anyone in particular, regardless of gender, nationality, or background.

One of the stores, which sells Chassidic men’s garments, does not cater to women, nor does it expect immodestly dressed women to enter the premises.

Though the Human Rights Commission tried their hardest, they could not find a single customer who had been turned away because of the dress code, or anyone who had been insulted by the insinuation.

In fact, customers and passersby from other communities, interviewed by the Commission, universally praised the storekeepers were being friendly and welcoming. A reporter who stopped by Sander’s Bakery to discuss the case was given enough free cookies to satisfy his children for a week!

But the Commission was determined to go ahead with the case, come what may. Out of all the issues that ail society, they thought this would be a winner for them.

They had ‘uncovered’ a terrible infringement on human rights, and were determined to nip it in the bud. For their crime of posting a polite suggestion, these shopkeepers would be hauled to court and forced to pay thousands of dollars.

When the case was first publicized, there was a hue and outcry from various quarters, including many liberal sources and those not usually sympathetic to the Orthodox community.

Mark Hemingway, a writer for the Weekly Standard wrote, “The New York City Human Rights Commission is putting seven Jewish business owners on trial tomorrow for discrimination in the heavily Hasidic neighborhood of Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The Orthodox Jewish business owners’ supposed crime? Posting a dress code in storefront windows.

“The….Commission’s case is so thin that one of their lead witnesses has a lengthy history of expressing anti-Israel sentiment.

“In order for the New York City Commission on Human Rights to conclude the posted sign was discriminatory, they employed a line of reasoning that was at once absurd and hostile to the free exercise of religion. In its initial claim, the … Commission tried to assert that because Hasidic Jews value modesty, the dress code was an attempt to foist their religion on others. In other words, restaurants and courtrooms could have an identical dress code posted, provided it was motivated by good taste or decorum. What makes the dress code discriminatory is not the code itself; it’s the speculation it have been motivated by religious convictions.”

“This is only the latest example of New York’s bureaucracy singling out Orthodox Jewish citizens. It’s another clear example of government needlessly overstepping its authority. After all, this request that customers abide by a dress code is no different than a fancy restaurant requiring jackets or a nightclub banning casual clothes, and yet places like Le Bernardin are not being targeted by the Commission,” said Councilman David Greenfield.

Dress codes have been around for many years, and are accepted, expected – and even respected -at many five star restaurants and in courtrooms. In face, the iconic Four Seasons restaurant in Manhattan has a very strict dress code which reads “Gentlemen wear jackets; ties are optional. If you prefer to travel without a jacket, you are welcome to borrow one of ours (sizes 38-52).”

Attorney Jay Lefkowitz, a Senior Litigation Partner at the Kirkland & Ellis, representing this case pro bono, explained to the Yated in an exclusive interview, “If you went into a Small Claims Court, you would see a sign saying plunging necklines are not allowed. The Four Seasons Restaurant insists that men wear jackets. Even your local country club won’t allow you to enter if you’re not dressed a certain way. It’s quite shocking that everyone other then Chassidic Jews are entitled to insist on a specific dress code.”

How did the Human Rights Commission explain this dichotomy?

According to Lefkowitz, they are focusing on intent, on what motivated the signs. “They claim a neutral observer can figure out that these are code words, to make some people feel unwelcome. They say that if the signs were placed due to a sense of fashion or propriety, somehow that is acceptable. But if it is motivated by religion, that is deeply offensive.

“This type of prosecution by the Commission makes no sense. One would think that it exists to protect shopkeepers from religious discrimination!”

It seems clear to many people, even those who are not traditionally supportive of Orthodox Jews in Williamsburg, that the Human Rights Commission has an axe to grind. After all, these are the people who fought against bike lanes and other progressive additions to their streets.

As the Weekly Standard elaborated, “Around the country, local and state governments are undermining free speech and attacking religious freedom with the aggressive use of human rights commissions, which have broad powers to haul individuals and business owners who run afoul of politically correct notions before sham trials. These trials can result in significant fines and are administrative proceedings that don’t give the accused many of the standard protections one would find in a real courtroom. In fact, the human rights commission is typically responsible for both prosecuting and rendering judgment on the accused.”

The Human Rights Commission had been harassing the shopkeepers for months, way after the signs were removed. Despite the involvement of Kirkland & Ellis, who had decided, on their own, to accept this case pro bono, the Commission insisted on having their day in court.

What made such a prestigious law firm, who has won many famous lawsuits, accept this case pro bono, spending over half a million dollars in legal and travel fees without charging a dime?

As Lefkowitz told the Yated, the evening before the trial, “I learned about the case from the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York City. When I heard about this complaint, which has no merit and makes no sense, I offered to represent the shopkeepers, pro bono. It’s all about ‘kol yisroel areivim zeh lozeh,’ one Jew sticking up for another. I’m not part of the Satmar community at all. In fact, I’m modern Orthodox, but I feel personally offended by the Commission’s conduct. I think this is a misguided prosecution.”

We asked Lefkowitz if he planned to charge the Commission with having an agenda?

“No, of course not. I’m not charging anything. I’m simply defending the shopkeepers, and hope to prove that these signs are not any form of discrimination at all. In fact, they are appropriate and legal. When people see these signs, they don’t feel excluded because they happen not to be Jewish. They are simply informed that the store owners want them to dress modestly.”

How do the shopkeepers feel about the lawsuit?

“I think they’re confused as to why they’re being singled out. They never told anyone to leave the premises or made their customers feel unwelcome in any way.”

They are also, as we discovered, incredibly grateful to the dedicated lawyers who are diligently working on their case. When the lawyers visited the shopkeepers a day before the trial, along with noted askan Rabbi Tzvi Weinreb, they were given the ‘red carpet’ treatment, provided with refreshments, and thanked effusively. The shopkeepers were in awe at the law firm for going to such great lengths, including flying experts from across the country, in order to uphold Constitutional Rights.

THE LAWSUIT: A HISTORY

On July 24, 2013, the issue first went to court. An administrative judge explained that it would be hard for the Commission to prove its claims, simply by saying the storekeepers were motivated by religious sensibilities.

Yet the judge, the Honorable John Spooner, graciously gave the Commission one more chance to prove its point. If they wanted to prove that the dress code discriminated against certain people, they needed to show the signs were a secret, coded attempt to keep outsiders away.

The Commission was hard-pressed to find disgruntled ex-customers, and so they created their own. They ordered a survey that would prove that neighborhood residents felt unwelcome.

The results of the survey? A vast majority of those questioned didn’t think the sign would make anyone feel discriminated against on the basis of religion. The defense also conducted a survey, and found that 87 percent of respondents thought the sign was welcoming to both men and women.

For the Commission’s survey, 600 people were interviewed. Out of all these people, Joshua Wiles was chosen to go to the witness stand, saying that the signs discriminated against certain people.

Who is Joshua Wiles? He is a well-known blogger and public school teacher in Bedford-Stuyvesant, who had been arrested while protesting Occupy Wall Street in 2011. His blog pages are filled with obvious anti-Semitic comments and innuendo. It’s not so difficult to figure out his agenda.

Along with Attorney Jay Lefkowitz, the shopkeepers were going to be represented by Lawrence (Larry) Marshall, a professor at Sanford Law School, a top constitutional attorney.

According to Rabbi Zvi Weinreb, one of Marshall’s close friends from his yeshiva days, “Larry clerked on the Supreme Court for Justice Stevens, (1986-1987) and is one of the stars in his field.”

Marshall regularly counsels Kirkland and Ellis, and has also agreed to represent the shopkeepers pro bono. Despite his hectic schedule, Larry, who was the original Executive Director of Project ROFEH, founded by the Bostoner Rebbe, agreed to speak to us shortly before the trial. He is a longtime Yated fan, and enjoys the paper immensely.

“What, in a nutshell, will this trial focus on?” I asked. “Is it open to the public?”

”The trial will take place on 40 Rector Street, and is open to the public. Yet the first phase of the trial will be rather technical. It will focus on survey evidence, on how random people on the street reacted to the sign.”

“What is your role in this case?”

“My role is that of counsel. Jay invited me into the case to work with him and his team of lawyers. It’s amazing to see the extent of how the firm has been committed to fighting for the rights of these shopkeepers. The firm has easily invested a half million dollars of its time.

“It’s all about principle of the matter. According to the Constitution, people have a right to control their environment, in ways that are not discriminatory. What bothers me in this case is, if you’re doing something in the name of fashion, it’s a non problem. You can have a dress code. If a court of law wants to enforce it, that’s okay, too.

“But if I run a store, who says I can’t say I have a way of life that means I want to surround myself with people who are dressed modestly? I have a right to control my environment just like anyone else. In any case, if someone is motivated by religious reasons, they’re supposed to have more protection by the law!

“Are you confident that the shopkeepers will win?”

“I never speculate about cases,” Marshall replied. “Yet we have a compelling case. The Commission has never gone after any other dress code, even those that are explicitly based on gender. For some reason that we don’t understand, they are coming after the Chassidim.”

“What happens after the trial? Will there be a verdict right away?”

“The judge will probably take it under advisement, and issue a written ruling. I hope the court case will be tossed out for lack of merit. If it isn’t, we will take it to the next level, and appeal to a higher court.”

Thankfully, the judge realized that the case had no merits, and urged the plaintiffs to withdraw their claim, instead of wasting the court’s valuable time. The Jewish community owes a debt of gratitude to the dedicated lawyers gave of their time, resources and talent to uphold these vital Constitutional Rights.

Attorney Jay Lefkowitz was very satisfied with the developments, “We’re very pleased that the Human Rights Commission realized that targeting the Chassidic community was inconsistent with human rights laws, and recognized that they’re entitled to the same rights as all other business owners in New York,” he told the Yated on Tuesday afternoon.

Agudath Israel of America greeted the settlement as “a sign of reasonableness” from the new city administration.

“While we believe that the signs, which simply requested that customers respect the community’s values with regard to dress, were entirely legal,” said Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel, the organization’s executive vice president, “we are happy that the issue here is closed.”

The commissioner’s statement asserted that, according to “the proposed agreement, representatives from the stores agreed that if they were to post new signs in their windows, they would say that while modest dress is appreciated, all individuals are welcome to enter the stores free from discrimination.”

Rabbi Zwiebel also expressed his view that “the case should never have been brought in the first place,” and that “the Commission’s pursuit of the Williamsburg store owners raised serious concerns of selective prosecution.”