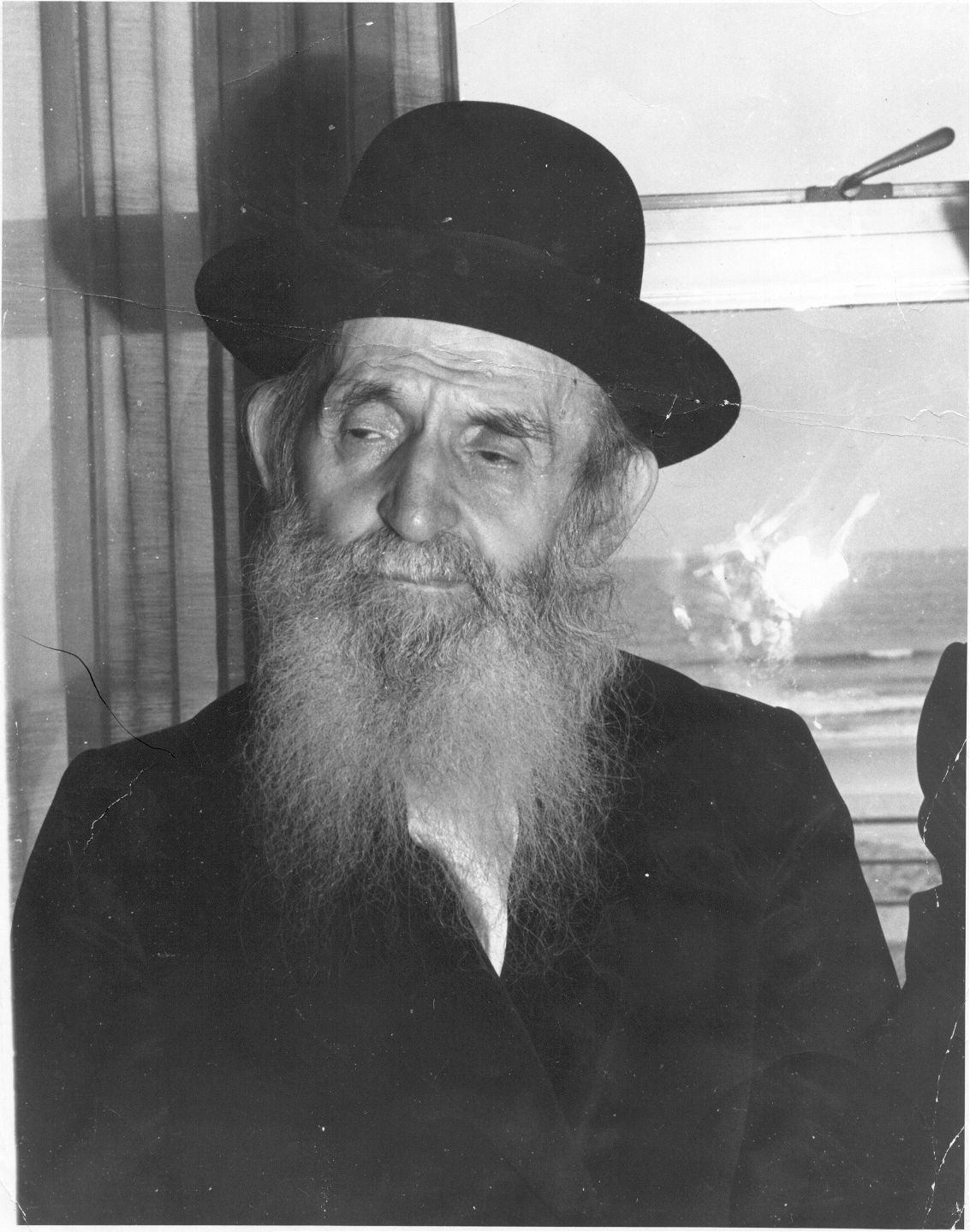

Upon His Yahrtzeit, 13 Av

Rav Yosef Eliyohu Henkin zt”l (5641/1881-5733/1973) was a gaon olam, well versed in all spheres of Torah. He was a major posek for American Jewry and was renowned for his chesed activities in his leadership role of the Ezras Torah relief organization. He was lovingly referred to as the mara d’asra of America.

Rav Henkin was born in Klimavichy, Belarus to Rav Eliezer Klonimus and Rebbetzin Fruma Shifra Henkin. Rav Eliezer Klonimus led the highly-regarded yeshiva in Klimavichy. Rav Henkin learned for six years in the yeshiva in Slutsk, where he became a talmid muvhak of Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer. He received semicha from Rav Yechiel Michel Epstein, author of the Aruch Hashulchan, the Ridvaz, and Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz. He served as rov in Smolian for nine years.

Rav Henkin immigrated to the United States in 1922 and settled on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He was asked in 1925 to lead Ezras Torah, the organization created to help destitute Torah scholars, and he did so with selfless dedication until his passing in 1973. He raised huge sums of funds for myriad families, who benefitted from his compassion and benevolence.

He was simultaneously a major posek for the Yidden of America, and his p’sakim were highly regarded amongst the Torahscholars of his generation. The following are several of his chiddushei Torah and piskei halacha so you may appreciate the great Torah personality that he was.

• • • • •

Rav Henkin notes that it has become common even for bnei Torah, when they daven Shacharis for the amud, to end off the brocha of “Boruch atah Hashem go’al Yisroel” silently, ostensibly so others should not answer amein to this brocha and create an interruption between go’al Yisroel and Shemoneh Esrei. This is done in order to be someich geulah l’tefillah, to join the brocha of redemption to Shemoneh Esrei (Brachos 9b).

Rav Henkin criticizes this custom and says that this goes against halacha. The main tefillas hatzibbur begins from the brocha of yotzer ohr, and the early custom was that the shliach tzibbur would daven the entire Birchos Krias Shema, including Shema itself, out loud. In fact, Sefardim daven in this manner.

Since it has become the tradition amongst Ashkenazim that everyone recites Birchos Krias Shema and Shema, the shluchei tzibbur have minimized their davening out loud and rely on the fact that the ikkar brocha, the main portion of the brocha, is the beginning, part of the middle, and the end, and saying those parts out loud suffices.

However, if the shliach tzibbur fails to say the beginning and end of the brocha out loud, he has not fulfilled his responsibility of tefillas hatzibbur even bedieved. With respect to the argument of those who desire to prevent people from inadvertently answering amein to go’el Yisroel, the Rama (Orach Chaim 66:7) rules that one should certainly answer amein to go’al Yisroel and it is not considered a hefsek.

Rav Henkin retorts that saying go’al Yisroel silently is more problematic, as it shows lack of concern of enabling others to hear the brocha. Rav Henkin concludes that every kehillah should correct this mistake and, paraphrasing the Mechaber (Choshen Mishpot 232:1), he says “ta’us l’olam chozeres – a mistake can always be rectified” (Kisvei Rav Henkin, volume 2, page 8, Gevuros Eliyohu, Orach Chaim 19:20).

• • • • •

The question of whether one may wash one’s hands in a modern bathroom of our times was asked of Rav Henkin. Other poskim hold one may not. Rav Henkin posits that today’s bathrooms are altogether different from the bathrooms that Chazal refer to and one may certainly wash one’s hands in a bathroom for all purposes and say the appropriate brocha thereafter outside the bathroom.

Our bathrooms are not just used for their designated purpose, but are also used for washing oneself, taking a shower, brushing one’s teeth, etc. Furthermore, after using the facilities, waste falls immediately into the water and is flushed down. Our bathrooms are therefore reckoned as a cheder emtza’i of a bais hamerchatz, where although one cannot recite Shema and tefillah, one is permitted to greet a friend with shalom aleichem (Orach Chaim 84:1).

Therefore, one may wash their hands there for tefillah and for a meal, reciting the brocha afterwards outside. In addition, if one walks into a bathroom without using the facilities, no hand-washing is necessary (Gevuros Eliyohu, Orach Chaim 1).

• • • • •

Rav Henkin said that one may use a paper cup for Kiddush as well as for washing before eating bread. There are those who question whether a paper cup is considered a kli, a utensil, altogether. Rav Henkin cites the Mishnah in Maseches Keilim (17:15) as proof that a vessel made from paper is indeed considered a kli.

Of course, it is preferable to use a kos na’eh, such as a silver becher, for a mitzvah. However, if a nice becher is unavailable, one may certainly use a paper cup both for Kiddush and for netilas yodayim (Kisvei Rav Henkin, vol. 2, p.27, Gevuros Eliyohu, Orach Chaim 86).

• • • • •

Rav Henkin was vehemently opposed to those who would make Kiddush and eat before tekias shofar. Rav Henkin outlines that the mitzvah of tekias shofar begins from sunrise. Once the obligation to perform the mitzvah begins, it is forbidden to eat until the mitzvah is performed.

Rav Henkin allows those who are weak and are unable to fast until after the tekios to eat privately before sunrise. He further rules that those who cannot wait to eat until the completion of all the tekios may eat after the tekios dimeyushov, the first group of shofar blasts, as these tekios are the main ones designated for Rosh Hashanah.

Rav Henkin, in face of opposition to this p’sak of not eating before tekios from prominent roshei yeshiva, who cited the minhag of previous gedolim who ate, quotes the Gemara (Chulin 7b) that “makom hanichu lo avosav lehisgader bo af ani makom hanichu li avosai lehisgader bo – Chizkiyahu’s forefathers left him a place in which to distinguish himself. I, too, my forefathers left me a place in which to distinguish myself.” He emphasizes that this p’sak is reckoned as halacha berurah, with no qualms about it (Kisvei Rav Henkin; Gevuros Eliyohu, Orach Chaim 158, 159, 160).

• • • • •

Rav Henkin paskens that when necessary, one may include in a minyan of ten men all those who come to daven or say Kaddish. Lechatchilah, of course, one should endeavor to daven with a minyan of kulam kedoshim, butin a situation where the minyan includes those who are not necessarily ideal for a minyan, one should not be mevatel the opportunity of saying Kaddish, Kedusha and Borchu. The other option would be the dissolution of the kehillah, which is a non-option.

Rav Henkin concludes that this is not in the category of “one shouldn’t sin in order that your fellow may gain” (Shabbos 4a). Rather, the gain here is a personal one that benefits the many (Gevuros Eliyohu, Yoreh Deah 64).

• • • • •

The Gemara in Rosh Hashanah (19b) states, “Gedolah misas tzaddikim k’sereifas bais Elokeinu – The death of the righteous is as great as the burning of the Bais Hamikdosh.” This contradicts the Medrash (Eicha 1:37) that says that the death of tzaddikim is greater than the burning of the Bais Hamikdosh. How can we reconcile these two divrei Chazal?

Rav Henkin, while eulogizing the Chazon Ish, said the following: The Gemara and the Medrash are referring to two different types of tzaddikim, and there is no contradiction whatsoever. The Gemara in Rosh Hashanah is speaking about Gedaliah ben Achikam, who was a noted and highly regarded leader of the Yidden. He was a public figure whose passing was similar to the destruction of the Bais Hamikdosh. Both losses were in the public sphere.

The Medrash, however, is speaking about a tzaddik who is not in the public eye, who delves intoTorah learning in privacy. He constantly toils in theTalmud and poskim. Even though he is not physically present when the Torah leaders meet in public, a bit of his greatness is felt in the realm of meitzitz min hacharakim, peering through the lattices. When such a tzaddik dies, the loss is even greater than the destruction of the Bais Hamikdosh. The people of his generation do not realize what they have lost. Hashem, though, does realize the loss that the world has suffered. Hashem laments the loss double-fold – the world has lost a tzaddik, and the world fails to realize the magnitude of this loss.

How does the Medrash know that the passing of such a tzaddik is a greater loss than churban haBayis? The novi writes concerning churban haBayis, “Vatered pla’im – She has descended astronomically” (Eicha 1:9). Concerning a tzaddik’s passing, the novi (Yeshayah 29:14) says, “Heneni yosef lehafli es ha’am hazeh haflei vafeleh – Therefore, I will continue to perform obscurity to this people, obscurity upon obscurity, and the wisdom of his wise men shall be lost.”

This posuk is referring to a tzaddik whose passing represents the double loss that Hashem laments, as the posuk stresses with “haflei vafeleh.” This loss is greater than churban haBayis, referred to simply as “pla’im” (Yeshurun volume 20, p. 283).

• • • • •

R’ Mendy Pollak learns and teaches Torah on Manhattan’s Upper West side.