The Trivial Issue of the Week

Israel has been preoccupied with a trivial matter of its own: a new public broadcasting corporation. I won’t even try to explain the issue in full. I will simply say that this controversy threatens to undermine the government. It has to do with the former Israel Broadcasting Authority, which the government has decided to turn into a public corporation. Prime Minister Binyomin Netanyahu wants to postpone the implementation of that decision for another year, but Naftali Bennett and Moshe Kachlon are opposed. The result has been a major clash between the county’s leading political figures.

Controversy even reached the Knesset Channel, as well as the Galei Tzahal radio station, which featured an anti-Zionist Arab on one of its programs. This angered Netanyahu himself, but Avigdor Lieberman, the Minister of Defense, took the matter one step further and summoned the commander of Galei Tzahal for “clarification.” That may be interpreted to mean a reprimand or a hearing, depending on whom you ask.

In short, these issues occupied our attention throughout the past week. Of course, we also monitored the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, watching as something that once seemed to be no more than a dream materialized into reality. Donald Trump has actually become the Republican candidate for president of the United States, defying a ll expectations.

ll expectations.

No Obligation to Inform

The Knesset will be disbanding for a lengthy recess, which will begin on Wednesday and will continue until after Sukkos. This gives me the opportunity to write about some lingering issues.

First, a few words about parliamentary queries. A parliamentary query is a question asked by a member of the Knesset, to which a government minister is required to respond. People tend to belittle the significance of these queries. Often, the minister’s response comes only after the question has been forgotten. For that purpose, there exists a device known as an urgent parliamentary query. When an urgent query is submitted, the minister is required to respond within two days in the Knesset plenum, and the Knesset member who submitted the question, along with two others, is permitted to question him further.

The Speaker of the Knesset, Yuli Edelstein, is particularly fond of urgent queries, which he himself approves. Those queries are answered in the Knesset plenum at the beginning of every Wednesday’s sitting, and Edelstein himself almost always chairs that portion of the sitting. Incidentally, Edelstein has been enraged over the past two weeks, since Minister of Transportation Yisroel Katz has refused twice to answer an urgent query concerning the light rail in Yerushalayim. (The query asks the minister to explain how he has contended that extending the light rail into places such as Rechov Golda Meir will reduce crowding on buses, while at the same time he insists that the light rail will operate in addition to buses, but will not replace them. This seems to be an outright contradiction. Moreover, if the train is allowed to travel in the public transportation lane of Rechov Golda Meir, then that dangerous thoroughfare, which has already claimed numerous victims, is likely to become even more perilous.)

Sometimes, it is clear that a parliamentary query has achieved its goal. This past week, Yaakov Margi of the Shas party submitted a query to the Ministry of Finance, noting that numerous Israeli citizens have received orders to disclose to the tax authorities the identities of the technicians who installed air conditioners in their homes. This was part of the tax authorities’ effort to locate tax evaders, but it also forced ordinary citizens to serve as government informers. Margi asked whether it was true, and whether a citizen who did not wish to inform on others would be required to answer the questions. These requests, incidentally, were received by thousands of families, mainly in Bnei Brak. It is not clear what prompted them.

The response was delivered by Yitzchok Cohen, the deputy minister of finance and another member of the Shas party. “I must tell you that I respect my good friend, Rabbi Yaakov Margi, very much,” he said, “but I don’t understand what prompted this question.”

“I am holding a questionnaire in my hand that was sent by the Tax Authority,” Uri Maklev said.

“But why should the entire Knesset have to focus on the trivial work of the Tax Authority?” Cohen said.

With that, Edelstein spoke up. “To be perfectly accurate, it was yours truly who decided that this topic was worthy of the Knesset’s attention,” he said. “When I saw that questionnaire, I decided that it was necessary for us to hear your informative response.”

Yitzchok Cohen then responded to the question. “The Tax Authority has no intention of taking any legal steps against a citizen who chooses not to respond to the questionnaire, if that is what is bothering you, Rabbis Margi and Maklev.”

Uri Maklev, though, had done his homework. He read aloud from the letter in his hand: “Dear Mr. and Mrs. ___. Based on the information we possess, you had an air conditioning unit installed in your home. By virtue of my authority under the Income Tax Ordinance, I request that you submit to me the details regarding the installation of the air conditioner on the enclosed form. You are required to respond to this letter within 30 days of receiving it.”

Dov Khenin added, “The letter is phrased as a demand. You are trying to reassure us that the Tax Authority will not force anyone to do anything, and that, of course, is the appropriate and desired situation. The wording of the letter, though, indicate otherwise.”

“I repeat,” Cohen responded, “and I will assure you as well, MK Dov Khenin, that the Tax Authority has no intention of taking any punitive steps against any citizen who does not respond to this request for information. Okay?”

Indeed, it was okay. But had the question not come before the Knesset plenum, it might not have been okay after all…

Discrimination Against the Observant

Last week, the Knesset dealt with the subject of the hostel for observant prison inmates. The hostel serves as part of the rehabilitation process for a prisoner, and it plays a critical role before the inmate becomes eligible for parole after serving two-thirds of his sentence. A year and a half ago, the hostel run by the religious wing of the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority was destroyed in a fire. Since then, it has not existed. Observant inmates, of course, cannot be housed in a chiloni hostel, where Shabbos is not observed. The clear result is that religious prisoners are severely disadvantaged.

Chaim Katz, the Minister of Welfare, admitted that the religious wing was the most effective part of the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority. “No one denies that the religious wing of the authority has been proven both efficient and successful,” he confirmed, “and it was recently backed by a study confirming that.” At the conclusion of his response, the minister promised to have the matter discussed in the Knesset Welfare Committee. But that was all.

Yigal Guetta, who submitted the query on the subject, hastened to say, “But, Mr. Minister, perhaps you can help with regard to the hostel.”

Chaim Katz did not even blink. “Since we have a low budget and you belong to a party that brings in money,” he said, “you should help us help you.”

In other words, he was placing the onus of securing the funds on Guetta himself. This is actually preposterous: Since when does a government minister ask a Knesset member to obtain the funding for a service under his jurisdiction? But Chaim Katz refused to reopen the hostel immediately, and the reason was simple: A religious prisoner, like any religious citizen of the State of Israel, is considered second class and fair game for discrimination. When the hostel for Arabs closed down due to lack of funding, though, the Arab Knesset members expressed outrage and it was reopened immediately, despite the financial woes of the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority.

You can consider these items to be in honor of the beginning of the Knesset’s summer recess. As I have mentioned in the past, the Knesset is probably the only workplace in the world where the employees wish each other a shanah tovah when they part ways before Tishah B’Av.

A “Bad Goy” and a “Good Goy”

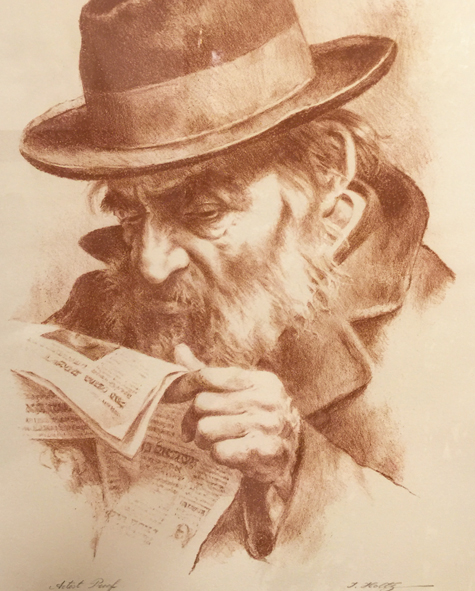

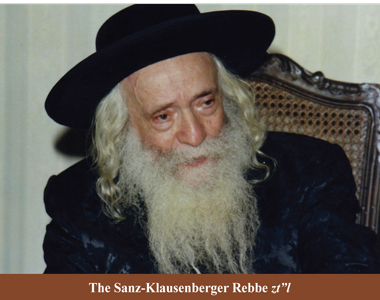

Last week was the yahrtzeit of the Shefa Chaim of Sanz-Klausenberg. A number of years ago, I began receiving the weekly internal publication of the Sanzer chassidus, which includes reprinted shiurim that the rebbe delivered during his lifetime. Ever since then, one could say that I have become his chossid. Every shiur is a pure delight. I myself cannot bear witness to his greatness in Torah, but the list of sources for every shiur is a testament to that on its own. He had an incredible store of knowledge that spanned the entire Torah. I imagine him sitting with a Chumash open before him, while his hundreds of listeners feel themselves being elevated by his words, perhaps even catapulted to the heavens themselves. Most of his shiurim were delivered in America.

It is amazing to see the power and determination displayed by the rebbe after he survived the horrors of the Holocaust. The Klausenberger Rebbe used his shiurim to transmit fundamental principles of hashkafah along with practical teachings. His shiurim were solidly constructed and delivered in captivating language, combining explanations of puzzling issues in the parshah with stories about his rabbeim and forebears, practical guidance for his followers, and even words of reproof delivered with fatherly love. Every  word of his shiurim exudes his love for his chassidim, regardless of the topic he discusses.

word of his shiurim exudes his love for his chassidim, regardless of the topic he discusses.

Studying the Klausenberger Rebbe’s shiurim has shown me the depth of the pain and sorrow his heart contained over his family’s suffering at the hands of the Nazis. I have come to recognize just how much physical and emotional torment he experienced. I also learned his perspective on chinuch: “Those who engage in the work of chinuch should know that our generation is not like the earlier generations… In our times, when fathers are busy earning a living and when mothers are no longer mechanech their children as in generations past, a mechanech must be both a father and a teacher to Jewish children. He must teach them Torah, as well as good and proper middos.” Elsewhere, the rebbe comments, “One of the scourges of this generation in America, which is one of the evils that came about because of Hitler and his cohorts ym”sh, is the fact that the youth have learned pride and insolence.”

The rebbe insisted that his chassidim strive and aspire for greatness, which includes developing sterling character traits. “The roshei yeshiva and mashgichim,” he declared, “must take it as their duty to teach their talmidim that in order to acquire the crown of Torah, it is vital for them to master derech eretz and good middos, as Chazal state that derech eretz comes before Torah. When they see a young man who is lackadaisical about his learning, they should attribute it to a lack of derech eretz.” The rebbe demanded that his bochurim and yungeleit apply themselves to learning until they had exhausted all of their energies. This was a subject about which he spoke often.

The rebbe viewed the Torah as the supreme value. “The holy Torah teaches us how to eat, how to walk in the street… Wherever a person goes, the Torah gives him the wisdom and sagacity to know how to act with proper character traits, so that he will not desecrate the Name of Hashem either openly or privately.” In one of his shiurim, the rebbe said, “My holy ancestor, the rebbe of Dinov, used to say that anything that does not have a source in the Torah is not included in truth. Therefore, if I were to hear a mortal person making the simple calculation that one plus one equals two, I would doubt his words… The only reason I believe that calculation is that the Torah states in the story of Bereishis, ‘It was evening and it was morning, one day,’ and then after another day it states, ‘It was evening and it was morning, a second day.’ That is how I know that two times one equals two.”

Every shiur exuded the rebbe’s love for others, even when its content was reproachful. At the same time, the rebbe did not mince words. He spoke with the greatest candor.

The Perils of America

Every few weeks, the rebbe would speak about the spiritual dangers of America.

The rebbe cautioned his listeners against such things as indulging in material excesses, shedding their Jewish garb, adopting leniencies in kashrus, introducing new practices in shul, changing the traditional style of learning, and other dangers. Nor was he a fan of the State of Israel, about which he said, “Look how a group of people who betrayed their own souls were drawn to emptiness and infected by the notion of establishing a state, which was devised and led by some meshumad.” He mocked the founders of the state for thinking that they had solved the problems of the Jewish nation.

The rebbe also warned his followers against becoming too close to the non-Jews of America. “It was terribly detrimental to the Jews who came to America in the generations before us,” he warned. “In those days, when Jews lived in poverty and privation in the towns and villages of Europe, America was a coveted destination for many people, who had heard the rumors that America was a wondrous land where money and gems could be found among the stones and trees. When a person came back to Poland after visiting America, everyone would be enthralled by his descriptions of the magnificent cities and immense buildings that existed there, and the ease with which a source of sustenance could be found. The people would be beside themselves with envy of the person who had visited there. All the more so when an affluent modern Jew from America would visit their towns, leaving behind a generous gift to the bais medrash. Then they would look at him with admiration and reverence. Many of the people yearned for the bountiful life of America, making all sorts of calculations to determine how they, too, could fulfill their dreams and emigrate there.

“Only a scant few wise people understood the bitter truth that the Jews who went to America turned their backs on Yiddishkeit and were quick to stray from the path of Torah and mitzvos. I saw a kol korei that was issued by the rabbonim about 80 years ago, in the year 5650 (1890), which stated that it was severely prohibited to travel to America, since it was impossible to lead a life of Torah and mitzvos there. There was no shemiras Shabbos and no kedushas Yom Tov, only a path to heresy from which no one would return to Yiddishkeit. (I saw this in the library of Yeshivas Torah Vodaas, which contains many writings from previous generations.) The main cause of the destruction of Yiddishkeit in the previous generation is the fact that the Jews suffered no persecution from the goyim when they came here, except for a few exceptional incidents, such as the events during the levayah of Rav Yaakov Yosef zt”l, the chief rabbi of New York, in the year 5662 (1902), when several non-Jewish youths harassed the Jews during the funeral procession and even hurled heavy objects at them from the rooftops. The fight that broke out between the Jews and non-Jews then caused several fatalities. But other than that, in general, the Jews found America to be a land of freedom and respite from persecution. This led them to be taken in by the pleasures of the land and by its non-Jewish inhabitants, and they slowly began to mingle with the non-Jews and to learn from their deeds, attempting to find common ground with the goyim of America and to see to it that their sons would speak fluent English and their daughters would get along with the girls of the land.”

The rebbe was an incredible storyteller. From time to time, he incorporated stories into his shmuessen in order to lower the tension levels among his listeners. This particular description of the perils of life in America was followed by a story as well: “Sometimes, the father of a family, a G-d-fearing, wholesome Jew from Hungary or Poland, would himself remain devoted to Yiddishkeit, but he would wish to educate his children in the ways of the land and send them to follow the paths of the goyim and to study sciences in the universities, so that they would become doctors or professors who would be able to support the entire family in dignity. There is a story about a certain Jew who was a yorei Shomayim. He immigrated to America and rose early on Shabbos to review the parshah and perform the mitzvah of shnayim mikra v’echad targum. In the middle of learning the parshah, he realized that it was late and he needed to wake up his son to go to work or to college, but since he was makpid not to speak in the middle of shnayim mikra v’echad targum, he went and stood at his son’s bedside and snapped his fingers, calling out, ‘Nu nu!’ as a sign that the time had come for him to go to work.

“Such was the state of affairs among the Jews who wished to endear themselves to the goyim,” the rebbe continued. “When the scourge of the ‘rabbis’ and the Reform Jews who came from Germany was added to that, which added evil to evil and destruction to desolation, it completed the process of undermining the foundations of Yiddishkeit and destroying the religion of Moshe and Yisroel. So it was that entire generations of Jews were assimilated among the nations. They and their children were lost forever to the Jewish people, and there was hardly a Jew who observed Torah and mitzvos who could attest that he came from the fifth generation of a religious family here in America. Where are the descendants of all the thousands upon thousands of Jewish people who immigrated here over the years? Even if we do not look back to the time when Columbus discovered America, and we merely examine the past hundred years, we would be hard-pressed to find a grandchild or great-grandchild of all the Jews who came to America during those days.”

Visits from the Gedolim in South Fallsburg

And now for another nostalgic tidbit.

Many of you are undoubtedly spending the summer in “the mountains.” I myself was there 35 years ago, when I learned at Yeshivas Zichron Moshe, better known as the Yeshiva of South Fallsburg. I spent almost an entire year there, after I was accepted to the Lakewood Yeshiva by Rav Shneur Kotler zt”l. I quickly came to feel that Bais Medrash Govoah was not the place for me. Lakewood was simply too large for me – and this was in 1980. How do you suppose I would have felt about Lakewood today?

The mashgiach of the yeshiva, Rav Nosson Wachtfogel, knew that I had come; he was supposed to oversee my growth. One day, he called me in for a meeting. I had davened Shacharis in the yeshiva that day, so I felt confident that I would not be facing rebuke. The mashgiach proceeded to make me an offer that I couldn’t refuse: “Go to South Fallsburg,” he said, “where my son [Rav Elya Ber Wachtfogel] is the rosh yeshiva. I promise you that you will succeed there.” I left Lakewood armed with a warm letter of recommendation from Rav Nosson and only after he had spoken with his son on my behalf. In addition, I had a connection with Rav Elya Ber by virtue of Be’er Yaakov. Rav Elya Ber had very warm ties with Be’er Yaakov as a whole, and in particular with Rav

Moshe Shmuel Shapiro zt”l and with the rov of Be’er Yaakov, my father zt”l.

Moshe Shmuel Shapiro zt”l and with the rov of Be’er Yaakov, my father zt”l.

But this story is not about me. It is about the Catskills. We spent the winter there alone, in the midst of the heavy snow and ice. There was not a single Jew in the area other than the bochurim and yungeleit of the yeshiva. We were surrounded by snow and by non-Jews. But then the summer months came, and it was as if the entire area was transformed into Boro Park. Stores sprang up like mushrooms, and camps and bungalow colonies were everywhere. All of a sudden, the world had come to us. In fact, it was more than that: We were the center of the world, because the mikvah was on the yeshiva’s premises.

All year long, the bochurim of the yeshiva lived in isolation, far from any Jewish community. It was as if we lived on a remote island, a situation that naturally helped us immerse ourselves in Torah and ruchniyus. I could write an entire book about my time in South Fallsburg, but the experiences that I remember most clearly are the encounters with the gedolei Yisroel, roshei yeshivos, and admorim who came to the yeshiva for the sake of its mikvah. I saw Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky, and the renowned admorim appear at the yeshiva. I stood outside along with the other bochurim and watched with awe as they came and went.

On a side note, those of you who are enjoying the swimming pools in your bungalow colonies have no idea how much effort was invested on your behalf. During my time in South Fallsburg, I once spent a single day helping the director of a nearby bungalow colony clear out the weeds that had grown over the swimming pool during the winter. When I returned to the yeshiva, I was completely exhausted from the heavy labor. That poor fellow, though, had to spend two months on the grueling job.

A Threefold Brachah

In conclusion, allow me to share one last story that I heard this week at Bikkurim, the convalescent home at the Ramada hotel for mothers after birth. While I was there, Mrs. Batya Zlotnick, the dedicated supervisor, showed me a group of three beautiful triplets whose loud cries filled the air in the nursery, and explained the story behind their birth.

The triplets’ father once approached Rav Yeshayahu Epstein, the loyal right-hand man of Rav Chaim Kanievsky, and said, “I would like to receive a special brachah from Rav Chaim – not just something stam, such as the word ‘buha’ [an abbreviation for ‘brachah vehatzlachah’] that Rav Chaim has been using over the past couple of years.”

Rav Yeshaya smiled and said, “Rav Chaim’s ‘buha’ is not ‘stam.’”

The yungerman waited in line, and when his turn arrived, he requested a brachah for children. Rav Chaim smiled his aristocratic smile and said, “Buha, buha, buha.” And so it was that the couple was blessed with triplets.