Yom Hashoah Ceremonies

As usual, we had an extremely eventful week. After all, our country is one that specializes in creating issues and upheavals. Thursday was Yom Hashoah, Israel’s Holocaust Memorial Day. I mentioned the day in this column last week, but at the time I was writing before Yom Hashoah took place, and now it is already behind us. The day was marked by dozens of ceremonies throughout the country, the most significant ones being a ceremony at Yad Vashem, where the prime minister spoke about Israel’s strength and power; an event at Kibbutz Massuot Yitzchak, where the deputy Chief of Staff of the IDF, Major General Yair Golan, succeeded in antagonizing everyone present (details to follow below); and one other event at the Chagall Hall in the Knesset, where the names of Holocaust victims were read aloud.

This annual Knesset tradition was instituted by the late Dov Shilansky, the Speaker of the Knesset during the Twelfth Knesset, who was born in Shavel, Lithuania. Shilansky himself was at the Stutthoff and Dachau camps during the Holocaust. The idea of the ceremony is for various public figures to take turns at the podium reading aloud names of their own relatives who were murdered in the Holocaust. It is a very powerful ceremony. The enormity of the deaths of six million Jews in the Holocaust often makes it difficult to grasp on more than an abstract level, but when one hears the names of individual people who lived before the war and died in the conflagration, the tragedy becomes much more immediate and shocking.

One of the participants in this ceremony was Prime Minister Netanyahu, who read the names of his own murdered relatives. Nechama Rivlin, the wife of President Reuven Rivlin, began to weep when she read aloud the names of her family members. The Knesset physician, Dr. Yitzchok Lifschitz, shared the names of his grandparents, who were murdered in Kletzk, and listed the names of their children. Rav Yitzchok Yosef, the Sephardic chief rabbi, recited Kaddish, and Rav Dovid Lau, the Ashkenazic chief rabbi, listed the names of his own murdered family members, both on the side of his father, Rav Yisroel Meir Lau, who is the most famous Holocaust survivor alive today, and on the side of his mother’s father, Rav Yitzchok Yedidya Frankel, the rov of Tel Aviv.

The Major General Ignites a Storm

Meanwhile, at the ceremony at Massuot Yitzchak, Major General Yair Golan succeeded in antagonizing countless people, giving the country’s newspapers fodder for endless headlines and drawing condemnation from numerous directions. How did he do that? Here is an excerpt from his remarks: “The Holocaust should cause us to think deeply about the quality of a society, and it should lead us to a fundamental assessment of how we, here and now, conduct ourselves toward the stranger, the widow, the orphan, and those who are like them. If there is one thing that frightens me about the memory of the Holocaust, it is identifying the disturbing processes that took place in Europe as a whole, and in Germany in particular, and finding evidence of their existence among us in the year 2016… It is proper and even necessary for Yom Hashoah to be a day of national reckoning and introspection, and that internal reckoning must address these ugly phenomena.”

In other words, Golan believes that some people in the State of Israel today are guilty of anti-Semitism and racial bias. It should come as no surprise that his words evoked the ire of many who heard them. Prime Minister Netanyahu ordered Gadi Eizenkot, the chief of staff of the IDF and Golan’s superior, to reprimand him. Minister of Defense Moshe Yaalon, meanwhile, declared that he agreed with the major general. Golan himself later apologized for his remarks, claiming that he was misunderstood.

As if to confirm the major general’s words, a terrible incident took place on Thursday morning, the morning of Yom Hashoah, in Teveria. These days, before the beginning of the zeman, are the final opportunity for yeshiva bochurim to vacation, and several bochurim were relaxing at the Kinneret when their bags were stolen from the beach. Those bags contained the bochurim’s tefillin, and the thieves – whoever they were – proceeded to burn the tefillin. The bochurim discovered the charred remains of their precious tefillin in the lavatory at the beach.

Is that not a display of anti-Semitism and racial bias? And it took place here in Eretz Yisroel. Many public figures, including MK Yitzchok Herzog, hastened to condemn the heinous deed. “It is shocking that tefillin were burned in Israel in the year 2016,” Herzog declared. Rav Dovid Lau commented that he was davening that the perpetrators had not been Jewish. These comments were quoted in the chareidi media, but other media outlets remained silent – a striking contrast to the nationwide uproar over Yair Golan’s comments.

The American Rabbi’s Secret

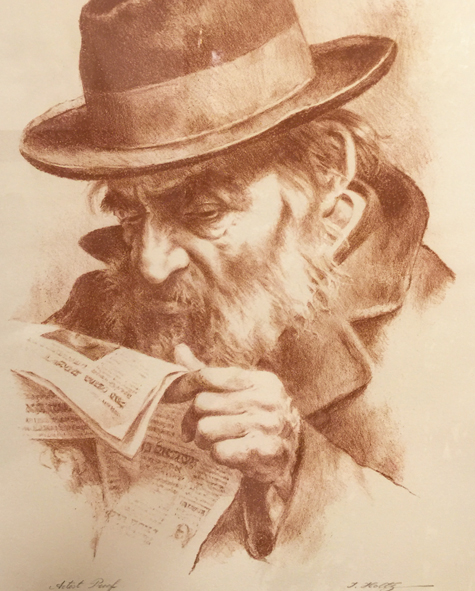

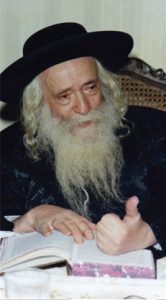

Later in that drashah, the Klausenberger Rebbe explained why he would not adopt a harsh stance toward the kapos: “It is not my intent to justify the crimes of the kapos, but in order to make the matter more understandable, I would like to tell you just one thing from which we can understand that we cannot judge them for collaborating with the evil Nazis during those unspeakable times. This is the story I would like to tell: Once, very early in the morning, after we had spent a full night involved in forced labor and we had been literally drained of all our strength, all of the inmates in the camp wanted to return to their barracks for a brief rest. At that moment, the wicked Nazis suddenly announced a roll call, as they often did in order to determine if any of us had gone missing. When they had finished counting their prisoners, we discovered that one inmate – a man of poor character who had no consideration for others – had done an awful deed: He had hidden in a secret place, and the result was that all of us were forced to stand outside in the biting cold without proper clothing to protect us. I have since learned that that man survived the horrors of the war, and today he is a rabbi here in America.

“When the Nazis discovered the prisoner’s absence, they began a search of the entire camp. When they finally found his hiding place, they dragged out his emaciated, weakened body, which barely had an ounce of vitality remaining in it, and the camp commandant ordered the kapo to whip the man many times before all of our eyes. The kapo indeed beat the man, but he did not strike him with all of his strength – a sign that he still possessed a Jewish heart.

“When the wicked brute saw that the kapo wasn’t using all his strength to deliver the blows, he shouted at him, ‘Is that how you hit? Let me show you how to strike!’ And the wicked Nazi murderer ordered the kapo himself to lie on the ground and began whipping him with brutal lashes, with all his might and terrible cruelty. It was a beating so severe that even the mightiest warrior would have been unable to stand after receiving such blows. After that incident, after the kapo suffered such terrible blows on his own flesh, I was not surprised when, ever since that day, he was unable to withstand the test when the Nazis ordered him to beat other Jews, and he struck them with all his might so that he himself would not be beaten in their place. Anyone who witnessed what took place in the camps can attest that it was the cruel, wicked Nazi murderers who forced the kapos to act as they did. They tortured them with starvation, thirst, and all sorts of other afflictions in order to strip them of their human dignity and to transform them into wild beasts. In Shomayim they know the truth: It is the wicked non-Jews, yemach shemam, not their long-suffering Jewish victims, who are deserving of punishment.”

The Holocaust, with its devastating impact on the Jewish people, is one of the most bewildering and troubling chapters of history. Every Jew has drawn his own lessons from its horrific events. In my view, the Shefa Chaim’s response to the Holocaust is one of the most edifying aspects of this historical nightmare. His life teaches us that a broken man can rise to the level of an angel, and that a person with a crushed and shattered body and soul can go on to build entire worlds. And today, in these days of Sefiras Ha’omer, when we work to perfect our bein adam lachaveiro, his words are a shining example of how to look favorably upon other Jews, even those guilty of the most heinous crimes.

A Tribute to the Heroes of Kiruv

Last Wednesday was the annual convention of Lev L’Achim. Every year, after the uplifting Yom Tov of Pesach, the kiruv activists of Lev L’Achim are treated to another inspiring event, an evening dedicated as a salute to those yungeleit who give of themselves every week, all year long, to their brethren who are thirsting for Yiddishkeit.

The Ohr Hachaim interprets the mitzvah of returning a lost ox to its owner as a metaphor for a child who becomes lost and must be returned to his father. In that vein, the dedicated yungeleit of Lev L’Achim – an organization that lives up to the meaning of its name, “a heart for brothers” – work tirelessly to help their lost brethren find their way back to our Father in Heaven.

Lev L’Achim’s annual convention consists of several parts, each of which is beautiful and inspiring in its own right. One part of the event is the maamad maranan verabbanan, when all the roshei yeshivos, communal rabbonim and other Torah leaders gather for an uplifting event led by the gedolei Yisroel. In general, Rav Aharon Leib Shteinman delivers a brief yet meaningful address. This gathering is a source of great encouragement to the leaders of Lev L’Achim, Rav Tzvi Eliach and Rav Boruch Shapiro, its spiritual leaders, as well as the members of its administration, such as Rav Eliezer Sorotzkin, Rav Avrohom Zaibald and Rav Natan Chaifetz, and all the national coordinators, midrashah directors, and thousands of other dedicated workers.

One of the most moving parts of the convention is the presentation of the “shailos uteshuvos,” a selection of the unique halachic questions that are brought to the activists of Lev L’Achim, and Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein’s answers to these shailos. “May I ask my parents to buy me a motorcycle if I know that my brother will ride it on Shabbos?” is question that has been asked. Another is: “May I lie to my mother about where I am going when I attend shiurim, since she doesn’t let me go there?” Another highlight of the evening is the question-and-answer session with Rav Uri Zohar. This year, the many guests at the convention were particularly moved by the event, particularly by Rav Shteinman’s arrival and his address. I imagine that you will read about it elsewhere in this newspaper. For some reason, I think that emotions were running particularly high this year.

Preventing the Fall

Another division of Lev L’Achim held another significant event, albeit one that received less publicity: On Tuesday, Lev Shomea held its annual chinuch convention in Yerushalayim. This convention, by nature, is designated for specific people (“marbitzei Torah, roshei yeshivos, menahalim ruchaniim, maggidei shiurim, and meishivim,” according to the announcements of the event) who spend the entire year on the front lines of the battle for the souls of talmidim in yeshivos, who are in need of kiruv and chizuk no less than their irreligious brethren. Lev Shomea is a telephone hotline manned by professionals in many areas who offer emotional support to yeshiva and seminary students experiencing various challenges. The organization’s aim is to save these youths before they fall.

The discussions at the event focused on a number of pressing issues: how to instill a sense of connection to the values of a yeshiva, how to guide a talmid in yeshiva to derive satisfaction from his learning, how to spot the early warning signs when a yeshiva bochur is experiencing difficulties, and the nature of the average yeshiva bochur’s struggles. The speakers and panel members were first-class experts in chinuch, along with psychologists and educational professionals. The highly insightful main address, which dealt with many of the challenges of our generation, was delivered by Rav Gershon Edelstein. Rav Eliav Miller, the chairman of Lev Shomea and a maggid shiur at Yeshivas Ohr Elchonon of Yerushalayim, solemnly informed the hundreds of attendees that as the Soton constantly steps up his efforts to ensnare the talmidim of yeshivos, Lev Shomea is correspondingly increasing its own efforts to save the souls of those youths. Like its parent organization, Lev Shomea has adopted the slogan of “Ki avdecha arav es hanaar,” a reference to its sense of responsibility for the youth of Klal Yisroel, but while Lev L’Achim concerns itself with the “youths” of secular neighborhoods such as Beit Hakerem, Lev Shomea focuses on the bochurim of chareidi enclaves, such as Bais Yisroel.

Speaking of bochurim finding satisfaction in learning, allow me to quote a vort that I once heard from Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro zt”l. On the posuk (Shemos 19:5), “And now, if you will listen to My Voice,” Rashi comments, “If you accept it upon yourselves now, it will be more pleasant for you in the future, for every beginning is difficult.” Rav Moshe Shmuel points out an incongruity in Rashi’s wording: Rather than stating that “it will be more pleasant for you in the future,” it would have been more logical for Rashi to say that “it will be easier for you in the future.” That, after all, is the natural contrast to the difficulty of a beginning. Based on this, Rav Moshe Shmuel proves that when people find Torah study difficult, it is solely because they do not experience the pleasantness of the Torah. Consequently, it will become easier to learn because it will be more pleasant. The hardship exists only at the very beginning, before the pleasantness is felt.

The Shefa Chaim’s Tears

On the subject of the Holocaust, permit me to quote something. In my view, the man whose life epitomizes both the horrors of the Holocaust and the heroism of a Jew who endured them is the Shefa Chaim zt”l, the rebbe of Sanz-Klausenberg. His gabbai, Rav Aharon Yehoshua Nussenzweig, once related: “The rebbe hardly ever mentioned his martyred children Hy”d, but listen to the following chilling story. This took place at the wedding of one of his children. On the afternoon of the chupah, something happened suddenly: The rebbe began speaking in a quiet tone and said, ‘Do you know, if my precious son – mein Lipa’le, mein Lipa’le – if he was alive today, he would have been such and such an age… If my Chaim Hershele had been alive today, he would have been this age… And mein Sima Brocha… Mein Boruch’l… Mein Chanale…’ And so the rebbe continued, enumerating all of his eleven sons and daughters. It was a dreadful sight: the scene of a father listing all of his children who had lived and been murdered. The rebbe’s voice cracked and broke, and he began sobbing endlessly. Suddenly, we saw him fall onto the sofa in his room and his streimel slipped off his head. For over 20 minutes, he cried terrible tears.”

The Klausenberger Rebbe’s strength and fortitude were literally superhuman. He rose from the ashes of the devastation of European Jewry, and he raised the spirits of an entire generation along with his own.

I recently wrote in the Yated about the Jewish kapos, the evildoers from our own midst who sold their souls during the Holocaust. Even about them, the Klausenberger Rebbe was prepared to speak positively: “Immediately after the end of the dreadful Holocaust, there were some Jews who wanted to follow an improper path and to deliver any Jew who had been a kapo into the hands of the non-Jewish courts. One day, I received a letter from the leader of the Jewish community in Argentina. He wrote that there was a kapo there who had been placed on trial, that he had related that I knew him from the camps, and that they wanted me to testify about his actions. I agonized over how to respond, for I remembered the wickedness of that man very well: He had beaten other Jews mercilessly, and I myself had suffered from his blows several times. But I finally decided to write the following to them: ‘I feel that such a person can be judged only by someone who was himself in a concentration camp and faced the same trying circumstances. A judge who hasn’t been through that gehennom isn’t fit to pass judgment on such a person.’ I added that I was not expressing an opinion about how his case should be judged, but that if it were brought before me as a judge, I would not be too quick to condemn him.”

Tel Aviv vs. Moscow

Sometimes, there is no need for words. Allow me to present to you a couple of lines from two newspaper articles recently published in Israel and you will see that there is no need for additional commentary.

Here is the first: “Chometz is being sold openly in many places throughout the country. Figures released on Chol Hamoed Pesach reveal that there are many places where chometz was sold over the course of the holiday.”

In sharp contrast to that piece of news, here is the second: “In honor of the holiday of Pesach, Russian President Vladimir Putin sent a letter conveying his warm wishes and his admiration for the preservation of Jewish tradition from generation to generation, alongside the great development of Jewry throughout Russia… In his letter, the president wrote, ‘I am certain that you will succeed in preserving your exalted traditions in the future as well. May there always be peace prosperity, and harmony among you. Have a happy holiday.’”

You see, sometimes additional words are unnecessary, for their purpose would be only to provoke thought and increase the readers’ understanding. In this case, these two news items speak for themselves. When a Jew is taken away from his religion, he can fall to the furthest depths.

A Free Nation

On Wednesday, the State of Israel marked Yom Hazikaron, which is officially known as “the Day of Remembrance for the Fallen of the IDF and the victims of terrorism.” Several years ago, the Israeli government decided that the country’s Memorial Day for fallen soldiers would be extended to include the victims of terror as well. Yom Hazikaron is always a difficult day, a time when the entire country weeps. There is no one in the country who doesn’t mourn the loss of someone who served in the IDF or who was murdered by terrorists.

The following day, Thursday, is Yom Haatzamaut, the State of Israel’s “Independence Day.” It is a somewhat forced holiday that has, in recent years, turned into nothing more than a day off from work and a time for organizing barbecues in the country’s forests. It is hardly the glorious celebration of nationalism that it was once considered.

On the subject of Yom Haatzmaut, allow me to share some information about Israel’s national anthem, Hatikvah. The author of the text was Naftali Herz Imber. The original poem consisted of nine stanzas, but only one of them was ultimately included in the national anthem, perhaps to keep it short. Not many people know this, but the decision for Hatikvah to become the national anthem was not made easily. Certain people, including Rav Avrohom Yitzchok Kook, had other suggestions. Some advocated adopting Shir Hamaalos as the country’s anthem, but the Zionist Congess sang Hatikvah, and that ultimately led to the final decision. The chareidi community has no sense of connection to Hatikvah, perhaps because it expresses a desire “to be a free nation in our land,” which can be seen as referring to “freedom” not only from physical subjugation, but from the mitzvos as well.

Naftali Herz Imber was born in Zolochiv, a town in Galicia, and was a yeshiva bochur who rebelled against his religion and sank to progressively lower depths. His personal life was hardly a source of pride; he was a vagrant and a drunker. He passed away in 1909, at the age of 53, from a disease of the kidneys caused by excessive consumption of alcohol. The first draft of the poem was written in 1877 in Romania; in 1886 he authored another version, using the pen name “Barkai.”

An amusing anecdote appears in a recently published book about Imber: “When the Sixth Zionist Congress was held in Basel, Imber used his last pennies to travel to the convention. When he arrived at the building where the delegates had gathered, the doorman looked at his neglected appearance and refused to allow him to enter. ‘I’m the author of Hatikvah,’ Imber insisted, but the doorman remained obdurate. He threatened to call the police if Imber did not leave. Imber moved off to the side and watched longingly as the carriages bearing the delegates to the congress arrived at the building. He didn’t know any of the people arriving, and he didn’t have the temerity to ask them to help him get inside. Through the open windows, he could hear the sounds of an impassioned argument. Herzl had brought up his plan to resettle the Jews in Uganda as a temporary solution until they would return to Eretz Yisroel. Many of the attendees objected, and some of them wept and sat on the floor as a sign of mourning. Suddenly, the sounds of song emanated from the hall. The delegates to the congress were singing Hatikvah to express their aspiration to settle in Eretz Yisroel. Imber recognized that the moment of which he had dreamed had finally arrived: His poem had become the national anthem. Yet he was still not permitted to enter the hall.”

In two weeks, we will be celebrating Lag Ba’omer. There is also a “holiday” of a different sort: Yom Yerushalayim, which is observed every year on the anniversary of the liberation of the Kosel Hamaarovi on the 28th of Iyar, the 43rd day of the Omer. On this day, a number of the senior residents of Yerushalayim will receive the Yakir Yerushalayim Award, among them Reb Menashe Eichler. Next week, bli neder, I will write about them.