SHABBOS 86: THE HEALING POWER OF A BRIS

When the Rebbe of Strikov zt”l attended a bris on Shavuos of 5751, he mentioned a certain ill person who was in desperate need of great mercy. When people expressed their wonder at why he did so, he explained, “We find a discussion in Shabbos 86 about washing a child with hot water on Shabbos, even if it is the third day after his bris. There we see that if a baby requires the bath and there is no hot water available, one can even heat up water. The infant is still considered dangerously ill, and if he needs to be washed, we do what needs to be done even though it is Shabbos.

“So, despite the fact that the immediate effects of the bris place a child in the category of a dangerously ill person, the Torah commands parents to perform the bris milah on their healthy infant. This duty holds not only in circumstances like today, when we have medical facilities that can deal with almost any medical emergency. In earlier times, when medicine was very primitive, the successful result of such a delicate operation would have been considered miraculous. Even if a person has no doctor or modern medicines available, he is still commanded to perform the bris milah on the eighth day. Clearly, there is some kind of havtochah that a baby who is circumcised will recover. If not, the Torah would never have commanded this! This is obvious when one considers that the mitzvah of ‘vochai bohem,’ that one must live to keep the Torah and not die, applies to bris milah as it does to virtually every other mitzvah.

“Since the mitzvah of bris milah includes a promise to heal the infant, fulfilling this mitzvah clearly brings with it a special aspect of healing. Mentioning a sick person at a bris is a segulah. It confers some of this healing on the ill, and in the merit of the bris he will be healed.” (Sichos Kodesh,Lech Lecha 5764, p. 2).

SHABBOS 87: THE DIRT-ENCRUSTED GEM

On thisdaf,we find that Moshe Rabbeinu first informed Klal Yisroel about the reward for upholding the Torah. Only then did he tell them the punishment for failing to observe the Torah.

Many people feel overwhelmed when they learn about the punishment for sins. This attitude is nothing more than a sad misunderstanding of the difference between a mitzvah and a sin. Someone who truly understands what every single mitzvah is can never be discouraged in the slightest. In the words of the Ramak and the Ramchal: “It is a vast kindness of Hashem that mitzvos are never ‘debited’ to compensate for sins. A sin is like dirt, which must be cleansed. In contrast, every mitzvah forges an eternal connection with Hashem. It follows that if one loses a mitzvah for any reason, he has sustained an eternal loss. But any punishment is finite. So how is it fair to cancel the eternal for the finite?

“This can be compared to a gem that is very soiled. Only a fool would throw the gem away, and in so doing cancel out both the gem and the dirt. A wise man will work hard to cleanse the gem.”

The Kochvei Ohr takes this to its logical conclusion: “Although every sin is horrible and must be cleansed, it is important to put sins and mitzvos into proper perspective. If one took all the sins from the beginning of creation and all the pain ever endured by any human being and put them on one side of a scale, and then placed any lonely mitzvah on the other side of the scale, he would likely be shocked at the outcome. The mitzvah would definitely outweigh the negative, since every mitzvah forges an eternal connection with Hashem. All the sins and pain together may translate to a long time, but in the end they are merely finite. The greater distinction is that the mitzvah has real existence, while the negative does not. How can we compare something which is limited – no matter how much of it – with a mitzvah that is infinite?

“It follows that for every mitzvah, a person should be filled with endless gratitude and joy, much more than winning a lottery or any other prize or distinction. He has attained another bit of eternity. Is it any wonder that people with emunah and genuine daas are filled with joy?” (Tomer Devorah;Ginzei Ramchal,Daas Tevunos, II, p. 59; Kochvei Ohr, Sason V’simcha).

SHABBOS 88: A FIERY TORAH

Rav Shlomo Yehudah Intreter zt”l was in transit to a labor camp during World War II, when he met an acquaintance from his days in the kloiz in Reishe. Sadly, due to the terrible persecution of Jews during this period, the old acquaintance had lost his emunah long before.

As Rav Shlomo was passing, this fallen chossid turned to him and said, “So, do you still believe in the Creator?”

“Absolutely,” Rav Shlomo immediately replied. “I believe b’emunah shleimah.”

“How can you still believe while living in such horrible times?”

Rav Shlomo gave a fiery response. “Listen, my friend: Tosafos in Shabbos 88 asks why Hashem put a mountain over Klal Yisroel and said, ‘If you accept the Torah, fine; if not, you die here.’ After all, hadn’t Klal Yisrael already declared, ‘Na’aseh venishma’?

“Tosafos explains that the Creator took account of the fact that when we received the Torah with fire and our souls flew out of our bodies, we would be tempted to recant from the shock of the experience. We were forced to agree, since once we had said, ‘Na’aseh venishma,’ we were no longer free to go back on our word.

“This great fire also alludes to the difficult times the Jewish people were slated to experience in the future due to our unique mission that was sealed in our acceptance of the Torah. Hashem put a mountain over us for times to come when it will be hard to be a Jew. During those periods, a person may be tempted to stop observing the Torah because of the many trials that are comparable to a consuming fire. Hashem was telling us that there will be times when we do not understand the workings of Divine Providence. Nevertheless, even during such difficult times, it is vital that we continue to keep to the Torah.”

These simple words spoken from the depth of Rav Shlomo’s heart inspired his companion to change his ways. From then on, he became a chossid like before, fulfilling the entire Torah”(Lechem Oni, p. 499).

SHABBOS 89: THE COAT OF ANGER

It is well known that Rav Yisroel of Vorkezt”l had a special garment that he set aside for wearing when he got angry. He never allowed himself to lose his temper unless he wore his special coat of anger. By the time he made it to the closet which held the coat, he had already lost all interest in being angry.

Once, he had very good reason to show anger, but he still was unsure if he should allow himself. He decided to consult with Rav Feivel of Gritza. “I will not allow it,” replied Rav Feivel.

Later, the Vorkever appreciated this. “You know, we find in Shabbos 89 that when Hashem will consult with the avos about the sins of the Jews, the only one who will stand up for us is Yitzchok Avinu. This seems strange, since Avrohom alludes to kindness – his main avodah – and we would expect him to be our main defender. Why is Yitzchok, the mainstay of gevurah, the only one to defend the Jewish people?

“The answer is that the avos all worked to transform their natures. Avrohom was born with a nature that leaned towards boundaries, so he made his life’s work chessed. Yitzchok was born with vast reservoirs of kindness, so he worked hardest on attaining gevurah.

“I, too, was born with gevurah and worked hard to be loving and kind. It would not be proper for me to show anger!” (Yemos Olam, p. 13).

SHABBOS 90: A DOUBLE DOUBT

On thisdaf,we learn about some of the worms that are liable to infest various fruits.

One man noticed that in his egg carton in Eretz Yisroel, there were very small book worms. He immediately figured that it was a mitzvah to inform people about this, since it was possible that when these eggs were used to make cake, a bug might be on them and fall into the batter. Since a whole bug is prohibited even if cooked, the cake would presumably be prohibited. Sixty times the mite wouldn’t help, since, due to rabbinic ordinance, a beryah, a complete creature, is not nullified in any amount.

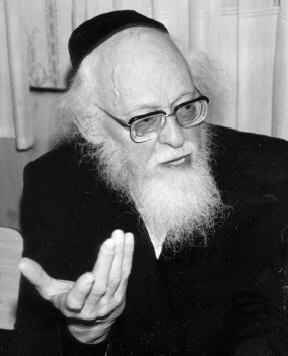

When this question was presented to Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv zt”l, he disagreed. “In this instance, there is a sefek sefeika, adouble doubt. Firstly, perhaps there is no worm. Secondly, even if there was a worm, maybe it wasn’t on the eggs used. And even if it was on the eggs, perhaps it fell into the batter, but maybe not.

“Therefore, one need not worry about this possibility at all. Nor should people be warned about this possibility” (Ashrei Ha’ish, Yoreh Deiah, Part I, p. 13).

SHABBOS 91: A CHANGE OF PLANS

The Sefer Zichronos writes: “Borer is one of the most complex melachos.”

On Shabbos, a man accidentally took some apples out of the bottom of a large bowl of fruit to eat much later in the day. When his host pointed out that this constituted borer, he wondered if there was any way to correct this. “After all, although borer for later is forbidden, if one takes for now it is permitted, since this is considered a normal way to eat. So if I change my mind and decide to eat these apples now, or someone else does, maybe it is as if I didn’t do the melachah after all.”

When this question was presented to the Ben Ish Chai zt”l, he disagreed. “Although one might have thought so, it is clear from Shabbos 91 that this calculation doesn’t work. There we find that one who carries a seed in the public domain on Shabbos in order to plant it is chayov chatos. It is clear that even if he later changed his mind and decided to store the seed, which requires much more for a chiyuv chatos, he is still considered to have carried a shiur on Shabbos. And the same is true regarding borer” (Shevisas HaShabbos, Meleches Borer, Halacha 3; Shu”t Rav Pe’alim, Part I, #12).

SHABBOS 92: SHARING THE BURDEN?

One Shabbos, a certain man accidentally pulled a rope which rang a bell. When his friend noticed this, he quickly also grabbed the bell and pulled. When asked to explain this bizarre action, he offered an interesting excuse: “I saw my friend in the middle of violating a serious prohibition with no way to stop him, but I realized that I could make his violation easier by doing it along with him. That way, it is two people doing the sin. As we find in Shabbos 92, two people who do a melachah are not obligated…”

The Maharam Shick ruled differently, however. “Even according to your logic that it is less serious if two people transgress,” he explained, “who said that two people violating a less serious prohibition is preferable to one person doing a serious sin? Quite the contrary. It is better for one person to do a more serious sin than for two people to do a lesser sin together!” (Shu”t Maharam Shik, Orach Chaim, Siman 127).