SHABBOS 44: THE REAL SOLUTION

On thisdaf, we find various halachos of muktzeh.

Living in Eretz Yisroel presents special challenges rarely found in the Diaspora. The degree of secular-religious tension that is unfortunately common in Eretz Yisroel is virtually unknown in Jewish communities in other countries.

One non-observant Israeli was so offended by the idea of a solely religious neighborhood that kept Shabbos that he decided to dedicate his Saturdays to disrupting the peace. All day long, he would drive his loud scooter through the religious neighborhood and then back again. Vroom! He kept returning, much to the annoyance of the neighbors.

One religious man had an idea of how to stop this travesty. “At a certain point, our secular friend will park his bike for a few minutes of rest. When he gets off the bike, we should either take the air out of his tires or, if this is forbidden, we should put a boot on the tire of his bike that will halt him once and for all.”

When they asked Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein if this is permitted, he replied that it is not so simple. “It is possible that removing the air from a tire on Shabbos constitutes the prohibition of soser. This may only be a rabbinic prohibition, however, since removing the air is merely destructive. One could argue that it is permitted to violate a rabbinic prohibition to halt someone disturbing the public, but there is a fairly clear proof that this is forbidden.

“As far as using a boot, this is also not simple, since this is engaging in uvdin dechol. Yet, it may be halachically permitted. I am not sure. Nevertheless, it would be better all around to daven that this misguided sinner will do teshuvah!” (Chashukei Chemed, Shabbos, p. 256-257).

SHABBOS 45: CARING FOR A PET

Having a pet can be therapeutic. One reason is that it helps a person focus on something outside of himself. Although the Arizal warns against having a pet if one is not absolutely certain that he will care for it properly, he warns that if a pet dies due to forgetfulness, it is on the cheshbon of the negligent owner. Most people do manage their pet’s upkeep in a satisfactory manner.

One new pet owner wondered if he is allowed to hold his pet on Shabbos. He was used to holding it and he found that refraining from doing so on Shabbos was difficult. We find on Shabbos 45 that it is prohibited to carry even a bird’s nest on Shabbos, since this is a base for something muktzeh: the birds. Tosafos explains that a bird is muktzeh even though it is a type that is fitting for children to play with. Although that seemed quite conclusive, the owner was well aware that halacha is not always readily apparent from a shallow learning of a sugya, so he decided to ask.

When this question was presented to Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach zt”l, he pointed out that Rav Chaim Naeh zt”l permits carrying a pet. “Although the Rosh writes that one may not carry an animal, and so does Tosafos in Shabbos 45, it seems clear that this is only regarding an animal that is not set aside to be carried like a pet.”

When Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l was asked a similar question, he disagreed. “It is clearly forbidden on Shabbos to even move a fish bowl that contains fish as an adornment for the home. This is explicit in Tosafos in Shabbos 45” (Shemiras Shabbos Kehilchasa; Igros Moshe, Orach Chaim,Volume IV, #66).

SHABBOS 46: A MIX-UP

This daf continues discussing the muktzeh status of lamps, candles and candelabras.

The vast Belzer Beis Medrashin Yerushalayim contains quite a few halls where baalei simcha can entertain guests. It is not too unusual for all the halls to be taken, especially on Shabbos.

One Friday night, there was a sheva brochos in one of the halls. The baalei simcha lit candles in the hall on one of the chairs. After the meal, the non-Jewish cleaning man cleared the candles off the chair and piled the chair up with the rest of the chairs in the hall.

When the person who rented the hall walked in the next morning, he noticed the candlesticks sitting on the side. He immediately began making inquiries and found that, indeed, the candles had been lit on one of the seats. A chair that had candles on it during shekiah is a bosis ledovor ha’assur and has the same halachic status as the candles themselves. Obviously, it was impossible to tell which chair was now muktzeh machmas gufo. Of course, since the chair would become permitted after Shabbos, it was a dovor sheyeish lo matirin, something that is destined to become permitted. Such an object that is mixed in with permitted objects of the same type cannot become nullified.

They were slated to make a simcha in the large hall, and removing the chairs and replacing them with other chairs was impracticable. There was no other hall available and this man had guests who were coming, albeit several hours after davening.

He asked the rabbonim in shul if it was somehow permitted for them to use the chairs in order not to compromise their simcha. One of the rabbonim pointed out, “The Noda B’Yehudah rules that dovor sheyeish lo matirin is only regarding something edible or something that is only used once, like firewood. In the language of the Gemara, ‘Instead of eating it b’issur, let him wait and eat it b’hetter.’ Although the Piskei Teshuvah brings this and implies that it is the halacha, most other authorities disagree. Perhaps they could rely on the Noda B’Yehudah to avoid ruining the simchah.”

The rabbonim immediately took this question to Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashev zt”l. The moment he heard the question, he immediately said, “It is a dovor sheyeish lo matirin that cannot become nullified.”

When the messenger explained the circumstance of the guests about to arrive, however, Rav Elyashiv ruled leniently. “In this instance,” he said, “they can indeed rely on the Nodah B’Yehudah” (Pischei Teshuvah, Yoreh Deah, siman 110, se’if kotton 6; Vayishmah Moshe, p. 247-248).

SHABBOS 47: A BRIEF PAUSE

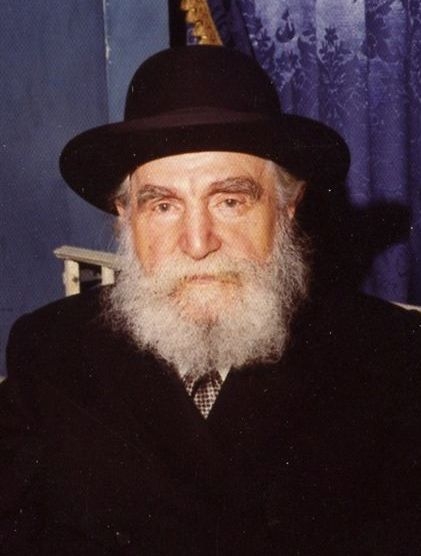

The Yismach Yisroel zt”l, the first Alexander Rebbe, was very sharp. When he decided that something was unacceptable, he conveyed it in a strong manner, often laced with his acerbic wit.

When the Rebbe was forced to stay in a resort town, he would take long walks every day. Those close to him would follow at a respectful distance, hoping to learn something from this great personage.

Such resorts would have musicians playing at various corners so that guests could enjoy the scenery with musical accompaniment. Once, the Rebbe stopped right near an orchestra playing relaxing music and paused for a short time. One young scion of a chassidic dynasty pointed out that it was possible that the Rebbe was trying to hide his greatness by standing there and acting like a simple person. “Who knows what he is really thinking?” the bochur mused.

When the Rebbe heard this, he cracked a smile and said, “You are right. I am certainly hiding. But hiding here with this music? You have forgotten a Mishnah in Shabbos 47: ‘Ein tomnin b’zevel – It is forbidden to hide in refuse!'” (Divros Kodesh, Va’eirah 5762, p. 4).

SHABBOS 48: “YOU SHALL SURELY REBUKE”

On thisdaf we find that Rabbah rebuked the servants of the Reish Galusa for transgressing various prohibitions on Shabbos.

Rav Hillel of Paritsch zt”l issued an important rule guiding how one should offer rebuke. “I heard from the Tzemach Tzedek that the double language of the verse, ‘Hochei’ach tochiach,’ should be understood just as we understand the statement regarding milah of “himol yimol.” We learned in Avodah Zara 27 regarding milah that the double language, ‘You shall surely circumcise,‘ teaches that only one who is circumcised may serve as a mohel. The same is true regarding rebuke. Only one who has corrected the problem in himself should rebuke others!”

Rav Hillel added his own explanation of this: “When does rebuke effect real change? When one has first rebuked himself regarding the flaw that he wishes to correct in another” (Likutei Dibburim, Part I, p. 121).

SHABBOS 49: THE HOLINESS OFTEFILLIN

The Imrei Emes zt”l gave an inspiring explanation of the deeper meaning of various halachos of tefillin. “In Shabbos 49 we find that it is forbidden to pass wind while wearing tefillin. This alludes to illicit thoughts that have no real substance. We also see that one may not sleep while wearing tefillin. Not only must one avoid negative thoughts while he has tefillin on, but his tefillin should bind him to holiness – the only true freedom – which is the opposite of sleep. In this vein, we find that slaves received nine of the ten kabin of sleep that descended to the world. Clearly, avoiding sleep alludes to attaining freedom. Shabbos is also an aspect of attaining cheirus.

“The Gemara there tells us that Elisha called his tefillin the wings of a dove. Tosafos there brings a Medrash that teaches that, unlike other birds which will stop flying when tired, a dove rests one wing while exerting itself with the other. Similarly, even when he falls, a Jew must do everything he can to at least fly with half his capacity, despite feeling spiritually challenged” (Imrei Emes, Parshas Bo, 5679).

SHABBOS 50: PRESERVING THE BEAUTY OF THE IMAGE

Rav Moshe Tzuriel learns an interesting lesson from a statement on thisdaf. “Our sages tell us that a person should wash his face and hands every day to honor his Creator. Rashi explains that it is a mitzvah to wash, since we are created in Hashem’s image. Similarly, the Medrash in Vayikra Rabbah (34:3) states that Hillel would wash himself every day. When Hillel’s students asked him why he did this, he explained, ‘If the king gave an image of himself to be viewed in a public place, wouldn’t the caretaker be careful to wash it every day?’

“The Ibn Ezra relies on a similar rationale in his explanation of the prohibition against self-mutilation: ‘As the verse concludes, we are children of Hashem.'”

Rav Tzuriel concluded, “Rashi also tells us that one should be careful not to ruin what is already pleasant. We can learn an important lesson from this. We see that one should not do anything to his body that will make him look less attractive, since even minor damage is a contradiction to these ideas” (Otzros Ha’agadah, Shabbos 50).