Mincha on Erev Rosh Hashanah had ended and the crowd in the Gerrer bais medrash was waiting for the Maariv that would usher in the new year.

The Gerrer Rebbe, the Bais Yisroel, whispered something to the gabbai, Reb Shea Noach. The gabbai walked to the bimah and made an announcement: “There are still seven minutes until shkiah.”

Sometimes, we are so focused on the future that we lose sight of the present. The rebbe was reminding his followers that there were still seven precious minutes with which to be mesakein the fading year.

What can be accomplished in seven minutes?

The Chofetz Chaim would often say that over the Yomim Noraim, we appeal to Hashem as a “Melech chofetz bachayim,” a King who desires life. As we ask Hashem to grant us the gift that He Himself appreciates, it stands to reason that to be granted the gift, we also have to be chofetz bachayim. If someone has a valuable watch that he wishes to entrust to a friend for safe-keeping, which friend would he ask, one who has no understanding of valuable items or one who possesses an appreciation for fine watches? Of course, he would turn to the one who knows how to treat an expensive timepiece.

The Chofetz Chaim would conclude that the King who desires life is more likely to bestow life upon one who values life; cherishes and realizes the gift being given every moment.

Rav Avigdor Miller would make the same point with the example of a storeowner forced to lay off one worker. He has a choice of who to keep. One employee is hard-working and effective, but always in a bad mood and giving off negative vibes. The other is less efficient, but always in a good mood, making customers happy and lifting the spirits of those around him.

Rabbi Miller would say that a sharp proprietor would keep the second worker, perceiving the benefit of having a positive person around. So too, Hakadosh Boruch Hu wants happy workers, those who are pleased to be doing what they do.

In the final “seven minutes” of the year, we can focus on 5776 and consider how things have progressed, how much we have received, and how fortunate we have been during the past year, and express our appreciation for the blessings we have been granted.

We should take a moment to contemplate how many times we panicked or worried over the past year and how many moments of fear we faced. Then, from the perspective of the final moments of the year, think about how many of those problems cleared up and how many of those situations were resolved.

Think of all the brachos we received since the past Rosh Hashanah, the children brought into the world, as well as our new accomplishments, opportunities, friends, vistas,

and welcomed maturity in Torah.

As we stand at the cusp of a new year and begin praying for life, goodness and blessings, we first must appreciate what we have been granted and offer thanks and gratitude.

This week’s parsha tells us how, as it discusses the mitzvah of bikkurim. The Jew brings his first fruits to the Mikdosh and offers thanks in a loud voice. As the posuk states, “Ve’anisa ve’omarta” (Devorim 26:5).

The mitzvah of bikkurim, which began with our entrance to Eretz Yisroel, forces us to contemplate our blessings. Following the winter, we see an orchard of bare branches. We care for the trees nonetheless. We engage in months of hard work and davening for the climate necessary for a good crop, as well as the proper measurements of wind and rain, and no plagues or pestilence. We continually check the status of our orchard.

Then, one day, after all the waiting, toil and prayer, we find a ripening fruit and tie a string to it to indicate that this fruit will accompany us to Yerushalayim, so that we can thank Hashem for the bounty we are confident He will bless us with. We express appreciation for the miracle of growth and our faith in the future guarantee that we will be blessed with a bountiful year.

The lesson of bikkurim is not only a perfect message for this time of the year, but a perfect metaphor for the blessings in our life. Barren fruit trees, looking like they will never grow again, surrounded by dirt and snow, offer much rationale for despair, until suddenly, one day, a tiny new fruit restores hope for the future.

Hakoras hatov, being appreciative, is a vital middah. The word lehakir, at the root of hakoras, has a double meaning. It means to appreciate and it also means to recognize. For in order to appreciate the good, you first have to recognize its existence.

Hakoras hatov necessitates hisbonenus, focus and concentration, for we must feel the gratitude. Hakoras hatov does not mean offering lip-service and empty thanks, which is demeaning to the recipient, but really appreciating what we received and the one who did us the favor.

The opening pesukim of the parsha refer to Eretz Yisroel’s qualities and its flow of milk and honey. We don’t always see the blessings. Sometimes all we see are hostile neighbors, stabbings, bombings, and too many people who know nothing about their heritage and religion.

We examine our own lives and find things wanting. We can concentrate on the good or we can focus on those areas of life where the good is not always apparent. We see the barren branches and fret and worry that they will never give fruit again. We plant seeds and they disappear, causing us to wonder if they will ever grow into anything.

We need to concentrate on the good. We need to believe that the good that is not yet apparent will soon be, when the barren branches will show a sign of life. We don’t despair. We maintain our faith that everything that happens is for the best; it’s just that some good is evident, while some is not. And still we are makir tov.

We see a world overcome by fear, with bombs exploding at every corner of the globe, civil wars ripping nations apart, diplomacy failing, and refugees spreading hate and anxiety. We see bombs go off in New York and New Jersey, and miraculously nobody is killed. We see politicians react by begging people not to think that Islamic terror is involved, though obviously it is. We see stabbings in Mid-America along with chants about Allah.

We see our brethren in Eretz Yisroel so removed from Torah that they fight to work on Shabbos. We see generations growing up in the Holy Land without any Jewish knowledge whatsoever. We pity them and wish that there was a way to reach them. They assume that all we do is burn garbage pails and throw stones. We daven at the Kosel and put out of our minds that secular groups are waging a strong battle to bring their movement to the holiest place accessible in Jewish life.

We recognize that the reality is that the seeds are underground, germinating, and concentrate on recognizing the good everywhere.

I thank Hashem that I was able to be in Eretz Yisroel for a few days last week and for Shabbos, basking in holiness, positivity and growth.

I was surrounded by a sense of awe and joy over the too-short duration of my visit, confident that what I viewed and experienced is a harbinger of what’s to come. I am grateful for the opportunity to have visited, and even more grateful for what I saw over the course of those few days.

I stood in the field and saw how seeds have become luscious fruits. I saw barren branches and I saw trees laden with fruit.

I was given a grand tour of Yeshivas Mir in Yerushalayim, and as much as I knew and heard about the Mir, there were too many amazing sites to count. The Mir represents a chain stretching back many generations. We know that the yeshiva was carried on the wings of angels, beyond the reach of the Nazis, serving as an island of Torah for so many. We know how the more recent roshei yeshiva led the Mir to new heights, how people like Rav Chaim Shmulevitz, Rav Nochum Partzovitz and others emerged as the leaders of so many of the generation’s rabbeim and rabbonim, setting many on paths of Torah greatness and understanding

More recently, we watched in awe as a physically handicapped but not debilitated Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel built and built and built, constructing the largest yeshiva on earth with love and superhuman energy. Then, suddenly, he was taken from us.

Now, almost five years later, we experience the atmosphere in the many halls of the yeshiva, the sound of Torah in its many botei medrash, the enthusiasm on the faces of those who learn there, the sheer hasmodah that engulfs you as you walk by people of every age on bench after bench, and the joy and serenity on the faces of yungeleit who likely have no idea how they will buy chicken for Shabbos. You think you know what the Mir is, but you don’t until you feel it, see it, hear it, and are overwhelmed by the thousands of lomdei Torah between its many walls and on the streets everywhere around it going to shiurim.

You walk through the Mir and you can feel the prophecies of Yeshayahu Hanovi that we read in the seven haftoros of nechomah. You walk through its halls and see how seeds planted over the decades are flourishing.

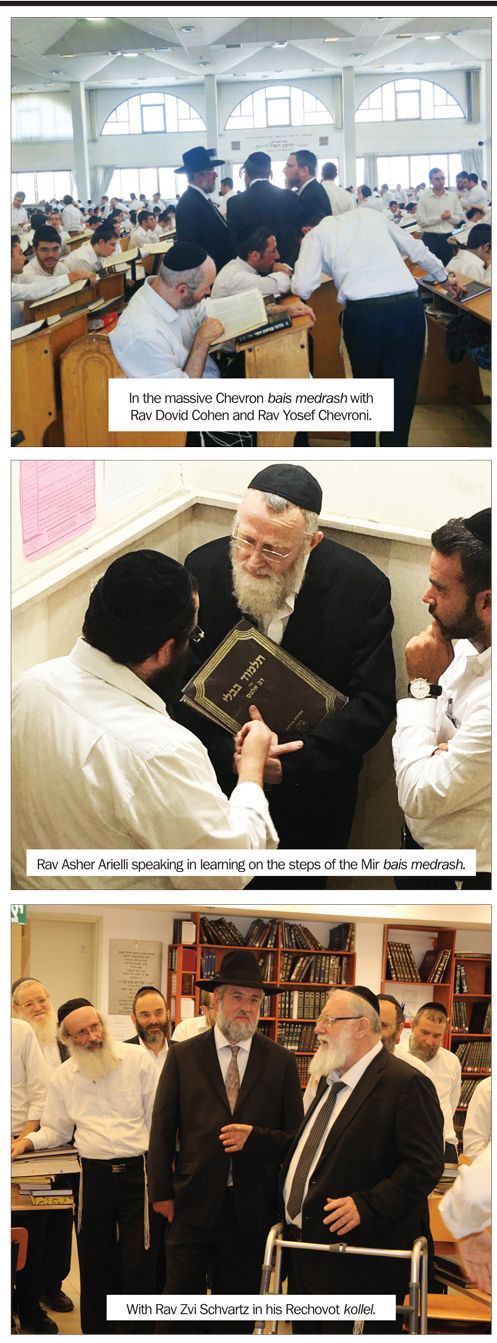

The image of Rav Asher Arieli, in his short jacket, with his humble posture and bright eyes, and his worn Gemara under his arm, as he speaks in learning with talmidim, typifies that miracle. Quietly, majestically, Torah is exploding.

The Chevron Yeshiva has its roots back in Lithuania. The Alter of Slabodka opened a branch of the yeshiva in Eretz Yisroel, in the ancient city of Chevron, where the clean-shaven, sharply dressed Litvaks added to the mosaic of the Holy Land, blessed with yiras Shomayim and exceptional depth in learning. Their dedication to Torah was seriously tested.

The horrific massacre that took place in that city and the yeshiva would have broken others, but the yeshiva relocated to Yerushalayim and forged on. Not many foreigners study there, and their campus is located off the beaten track, so many of us are not familiar with what goes on there. We know about the glory years, when virtually every future rosh yeshiva in the country learned there, but are unaware of the great edifice of Torah that it is today. I had never seen the Chevron bais medrash until last week. What an amazing site! Fourteen hundred bochurim fill the cavernous room, exploding with Torah.

Many seeds were planted to blossom into this burgeoning bais medrash that draws some of the best bochurim from all over Eretz Yisroel who wish to toil in Torah. In the middle sits the rosh yeshiva, Rav Dovid Cohen, speaking in learning with bochurim.

Many seeds were planted to blossom into this burgeoning bais medrash that draws some of the best bochurim from all over Eretz Yisroel who wish to toil in Torah. In the middle sits the rosh yeshiva, Rav Dovid Cohen, speaking in learning with bochurim.

It was humbling to stand there, being shown around by the rosh yeshiva, Rav Yosef Chevroni, but it was also very thrilling to see how Hashgochah orchestrated for this magnificent orchard to grow. Rav Chevroni showed me the yeshiva dormitory, which is being expanded to accommodate the growth, and a new dining room, which is being constructed to feed the ever-increasing number of bochurim. Walking around the bais medrash and expanding campus, observing the many fruits nobody ever thought possible, I was heartened, confident about our future and grateful.

I traveled to Rechovot to see the completed Halichot Chaim Kollel and community center that its leader, Rav Zvi Schvartz, has been dreaming about for the past 18 years. Few gave him any chance of succeeding in his dream to construct a building to house his 70-member kollel and center for kiruv in the cosmopolitan Israeli city. It was fascinating and invigorating to see what one dreamer has been able to accomplish, and to think about the Torah that will be studied and spread in the building that he labored to build for the past two decades, overcoming opposition, bureaucratic red tape and financial challenges.

Sometimes, we fail to see the larger picture. We get locked into the moment, seeing only that which is immediately in front of us. Now, at year’s end, we have to take a step back and look beyond our immediate field of vision.

A chossid endured the painful loss of a child and was unable to cope with the anguish. He traveled to the Kotzker Rebbe for comfort and solace.

As the man was a talmid chochom, the rebbe began the conversation by speaking to the grieving man in learning. The rebbe cited a Rambam and discussed difficulties he had with it. The visitor was able to explain the seeming contradictions and show the rebbe how the words of the Rambam were laden with meaning.

Seeing that the man was able to answer his questions on the Rambam, the rebbe brought up difficulties he encountered with a Tosafos. Again, the fellow had a nice p’shat.

“Yes, but what about the Rashba,” asked the rebbe.

“It’s not shver,” the man answered. “I’ll show you why.”

The rebbe looked at him and said, “So the Rambam has an answer, Tosafos has a p’shat, and there is no difficulty in understanding the Rashba…

“Don’t you think that there is an explanation, as well, for the decisions of the Ribbono Shel Olam?”

The chossid was comforted.

It often takes time, but we are given glimpses to bolster our emunah. There is always an answer.

In Chevron Yeshiva, I noticed the name “Zev Wolfson” over the main entrance. Mr. Wolfson was emphatic about not having his name on buildings, so I knew that there was a story here. I asked Rav Chevroni about it.

“Let me tell you a story,” he said. “When my father built this campus, there was a crisis. Overnight, the price of cement and other building materials rose sharply, putting the task of constructing the buildings beyond reach. There was so much money already sunk into the buildings, and he was unable to raise more. He was unable to go on. All his contacts had been tapped and nobody was interested in contributing more.

“Everything was in jeopardy. The yeshiva could have closed.

“He reached out to Mr. Wolfson, who responded that he would pay to put up the buildings. He saved the yeshiva. He literally saved the yeshiva.

“As the chanukas habayis approached, my father invited Mr. Wolfson to participate in the celebration. After all, without him, there would be no buildings. My father really wanted him there to publicly express his appreciation. Besides, Mr. Wolfson deserved to see the fruits of his dedication. But he refused to come. My father asked him a few times, and each time the answer was the same: ‘No. No. No.’

“Finally, it was the day before the chanukas habayis. My father was very emotional about meriting to complete the buildings and move into them. He felt that Mr. Wolfson should be there to share the same feelings of satisfaction. He called Mr. Wolfson’s office to speak to him. ‘He’s not here,’ the secretary said.

“‘Where is he?’ my father asked.

“‘I don’t know,’ said the secretary. ‘He left and said he’d be back in two days. He said that he can take no calls.’

“That was that. My father gave up. He called after the two days to report to Zev on how the chanukas habayis went. He said, ‘Zev, you really should have been there. You would have had such nachas.’

“The philanthropist responded, ‘Who says I wasn’t there? I was there. You convinced me that I had to be there. I came. I stood in the back. I watched. I enjoyed every minute. And then I flew home.’”

Zev Wolfson appreciated what he had and why Hashem gave it to him. He sought neither power nor glory, but rather worked to take inventory and build. He lived his life to its fullest by always challenging people to do more and to do better to increase Torah and G-dliness in the world. He always challenged himself to do better and seek out people and institutions to help.

That’s what we need to do in the final “seven minutes” and seven days. We need to step back, and without ego or other negios consider what we have been blessed with over the past. Think about what we have been given. Think about what we can do with what we were given. Think about what we have accomplished. Smile and say thanks to Hashem for the year that is ending.

Hashem, bless us during the coming year, for we are chafeitzei chaim, appreciative, believing and confident that we will use the blessings for their intended purpose.