International Expert Talks Daylight Saving Time

Benjamin Franklin conceived of it.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle endorsed it.

Winston Churchill campaigned for it.

Kaiser Wilhelm first employed it.

Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt went to war with it, and the United States fought an energy crisis with it.

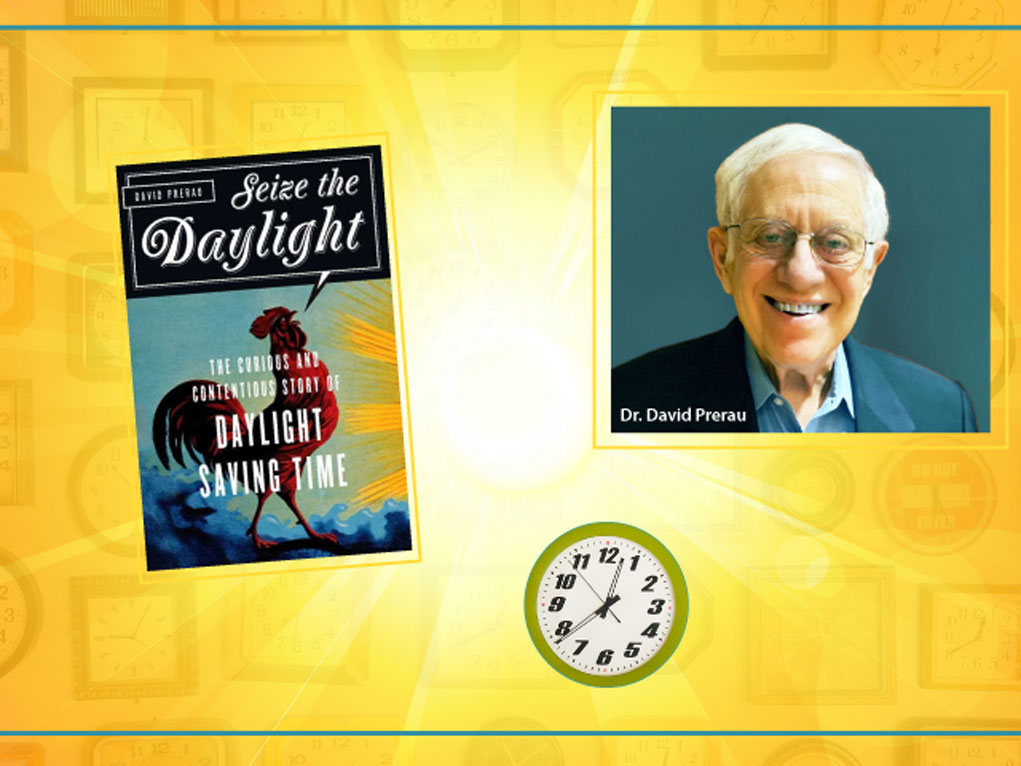

This riddle is posed by Dr. David Prerau, a leading international expert on the subject of daylight saving time, in his book, Seize the Daylight: The Curious and Contentious Story of Daylight Saving Time.

“For several months every year,” Prerau continues, “for better or worse, daylight savings time affects vast numbers of people throughout the world. And from Ben Franklin’s era to today, its story has been an intriguing and sometimes bizarre amalgam of colorful personalities and serious technical issues, purported costs and perceived benefits, conflicts between interest groups and government policy makers. Daylight savings time impacts diverse and unexpected areas, including agricultural practices, street crime, the reporting of sports scores, traffic accidents, the inheritance rights of twins, and voter turnout.”

The topic burst on the political scene abruptly two weeks ago, when the Senate surprised the country with a unanimous voice vote to make daylight saving permanent. This would mean no more changing the clocks twice a year, just having an 8:20 a.m. netz in winters and the earliest Shabbos at 5:15 p.m. in New York.

Many people thought the law had passed already — the Senate bill would change to daylight saving time on November 2023, and stay there permanently. But the House, which now gets to debate it, will probably be a lot less likely to approve it, says Dr. Prerau in an interview with the Yated.

The topic is a bit whimsical to write an entire book on. Like the story of how the sage of Chelm suggested saving sunlight in a barrel for nighttime hours, the concept of politicians playing with the clock has always been amusing. And Prerau has several pages of humorous quotes on the subject.

“An extra yawn one morning in the springtime, an extra snooze one night in the autumn is all that we ask in return for dazzling gifts,” Britain’s wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill mused. “We borrow an hour one night in April; we pay it back with golden interest five months later.”

President Harry Truman called daylight time, with its hours of wasted sunlight early on winter mornings and early evenings, “a monstrosity in timekeeping.”

Benjamin Franklin first thought of this timekeeping monstrosity in 1784, during a stint as US envoy to France.

“An accidental sudden noise waked me about six in the morning,” he wrote in a letter to the Journal de Paris, “when I was surprised to find my room filled with light. I imagined at first that a number of lamps had been brought into the room; but rubbing my eyes I perceived the light came in at the windows.”

“Still thinking it something extraordinary that the sun should rise so early,” continued Franklin, 78 at the time, “I looked into the almanac, where I found it to be the hour given for the sun’s rising on that day.”

Franklin’s discovery led to “several serious and important reflections.” Had he risen at noon as usual, he would have slept through six hours of sunlight. In exchange, he would have been up six additional hours by candlelight that evening. Since candlelight was much more expensive than sunlight, Franklin’s “love of economy” induced him to “muster up what little arithmetic” he was master of to calculate how much the city of Paris could save by using sunshine instead of candles.

Prerau’s book is crammed with the unexpected consequences of daylight saving. For example, a man born just after midnight managed to avoid getting drafted into the Vietnam War by arguing that under standard time, he was born the previous day, which had a much higher draft lottery number. Patrons at a bar in Athens, Ohio, rioted when the tavern closed an hour early. And in Antarctica, despite the lack of daylight in the winter months and darkness in the summer, many research stations still observe daylight saving time to keep the same time as their supply stations in New Zealand.

Under Amtrak rules, to keep to published timetables, trains cannot leave a station before the scheduled time. So when the clocks fall back one hour in the autumn, all Amtrak trains in the United States that are running on time stop at 2:00 a.m. and wait an hour before resuming. Overnight passengers are often surprised to find their train at a dead stop and their travel time an hour longer than expected. And when daylight saving time goes into effect in the spring, trains instantaneously become an hour behind schedule, so they speed up make up the time.

In addition to his research into the history of daylight saving time, Prerau was a key contributor to the largest technical study ever performed by the Department of Transportation on its effects. He served as a consultant to Congress when daylight saving time was last extended, by the Bush administration, and a consultant to the British Parliament.

It took us all by surprise when the Senate voted unanimously to make daylight saving time permanent. Why does the government have an obsession with playing with the clocks?

What I think is happening is that the current system is not perfect. And so, when people see problems, they think they can cure it by making a major change. But sometimes the cure is worse than the problem they’re trying to fix.

Nobody likes changing the clock in the spring, when you lose an hour of sleep. Some people it only affects a little, and they don’t even notice it. Some people it affects a little more and it takes a few days to adjust. But nobody likes it. In addition, there’s been some findings relatively recently that for the first day or two after that change, there are some negative effects, like an increase in traffic accidents. That got a lot of publicity.

I think people just thought about that problem of the change, and said, “Wouldn’t it be nice if we didn’t have to change the clocks?” So one possibility for not changing the clocks is to have daylight saving time year round, and that’s what the Senate voted on. Of course, there are a lot of problems with that, but the Senate obviously didn’t investigate at all; they just passed it very quickly on a 100 to zero vote.

But the House of Representatives is going to have a much lengthier analysis. And I think they will look at some of the pros and cons a lot more than the Senate has.

I see that you were consulted in the past by Congress on this topic during the run up to this bill. I didn’t even know there was a run up to this vote, but it seems that there was.

Not really. I was not consulted by the Senate. I mean, a long time ago, when we extended daylight saving time in 2007 based on a law passed in 2005, we added about an extra month of daylight saving time, and I was involved with that. I dealt with some of the sponsors of that bill in Congress. But this current thing came about without my participation. I did speak a little bit to the members of the House committee, and we’ll see what happens as that goes forward.

Does your curiosity in the subject stem from an academic interest, or do you have a strongly held opinion on it?

I was working for the US government as a PhD researcher, and I was involved in several different projects. One of them was to look into the technical benefits of daylight saving time, how it affected traffic accidents, energy usage, and so on.

Which government agency did you work for?

The US Department of Transportation. The Department of Transportation is the part of the government that is involved with anything to do with time, such as time zones. The time zones were originally developed by the railroads, so they have a link to transportation there.

I worked for the Department of Transportation research lab, and I got involved with a study. While I was doing it, I got interested in the whole history of daylight saving time and I found out that nobody knew much about it. So on the side, I started looking into where it came from, who started it, the history and the anecdotes and the stories and the conflicts and everything else. And I found out some very interesting history — the basic concept goes back to Benjamin Franklin in 1784, though the proposal that led to what we have now came in 1906 or 1907 in Britain.

So it has a long history — it’s been in use for over 100 years.

Can you summarize the basic thesis of your book?

Well, it’s a historical book. You have to read the whole thing. It has a lengthy history, and for each time period, different situations occurred. During World War I, it was put in place primarily to help with the war effort and save energy for the war — all the countries on both sides of the war implemented it.

After World War I, some countries kept it and some didn’t. And then World War II came, and again, every country on both sides put in daylight saving time to help with the war effort. After World War II, again, some countries kept it and some countries didn’t. The United States made it optional — every state and city could decide if it wanted daylight saving time or not.

It eventually became very widespread but a very non-uniform way. So the government passed a law in 1966 stating that you could have daylight saving time, but it had to be statewide, and all the states that had it would have to start and end it on the same dates. And that’s basically the law we have today.

Are there states that don’t have it today?

Yes. There are two states that don’t have it, for very specific reasons that are different from all the other states.

Hawaii doesn’t have it because it’s by far the most southern of the states. It’s closest to the equator, and near the equator sunrises and sunsets don’t change very much over the year. So that minimizes the benefit of daylight saving time.

The other state that doesn’t have it is Arizona, but for a completely different reason. In the populated areas of Arizona, primarily Phoenix and Tucson, it is extremely hot in the summer. It’s so hot that they don’t want an extra hour of daylight, which is what most of the rest of the country loves. It’s so hot there that they stay indoors during the day; they wait for the sun to go down to go outdoors.

Just to show you how it works, New Mexico is right next to Arizona, but they have daylight saving time. The reason is that the big cities in New Mexico — Santa Fe and Albuquerque — are up in the mountains, so it doesn’t get too hot in the summer, unlike Phoenix and Tucson in Arizona which are essentially sea level and very hot.

But the other 48 states, besides for Hawaii and Arizona, have daylight Saving Time.

It’s interesting that you mention Benjamin Franklin as the first to advocate for daylight saving; he was also the one who first discovered electricity. Before electricity became widespread, there was sort of a natural daylight saving time — people

went to sleep at dusk and woke

up at dawn. They couldn’t do much during the night hours. Electricity made it possible for people to be productive during the night.

Well, yeah, when the country was mostly rural, people would do things by the sun. When we started having people living in cities and going to work at a certain hour based on the clock, life was more dominated by the clock rather than the sun. So if you had to be at work at a certain time, you couldn’t get up earlier than wherever the sun rose. On the other hand, if the sun rose at 6:00 a.m. and you had to be at work at nine, those hours would be wasted.

The idea of daylight saving time is to move those hours — the spring, summer, and fall hours of daylight in the morning that are generally not well used — to the evening, when more people could make use of them.

But that doesn’t work in the winter. And that’s the problem with this proposal that the Senate has passed. In the winter, when the sunrise is late, if you move the sunrise later, you start to get a big negative effect. Because now, a lot of people are waking up in the dark, commuting to work in the dark, and sending their kids to go to school on dark city streets or waiting on the side of dark country roads for buses.

The most important thing in history that has to do with the current proposal is that we actually did once try year-round daylight saving time. In 1974, there was an unexpected energy crisis due to the Arab oil embargo. The government was looking for ways to try to save energy, and one thing they thought they could do is expand daylight saving time to be year-round, since people use less electricity during the day. They put in a temporary emergency act to have year-round daylight saving time for two years.

What happened was that the first winter it was used, it quickly became very unpopular. As I said, people didn’t like getting up in the dark, going to school in the dark, sending their kids to school or going to work in the dark. It wasn’t always darker, but in most of the country where it’s cooler in the winter, it’s also colder, because you’re sometimes getting up before sunrise instead of after sunrise, when the sun hasn’t had time to warm up the land.

So even though it had been put in as a temporary measure that would only last for two years, Congress repealed the second year of winter daylight saving time. We went back to having standard time in the winter and daylight saving time in the spring, summer, and fall, which is what we have now.

So we did try to have permanent daylight saving time, at the Senate proposed now, and at least in 1974, it was extremely unpopular.

So what happened now? Are people warming up to the idea of sending the kids to school in the dark? Do they now not mind commuting in the dark?

No. I don’t think the Senate looked into any of that and I don’t think most of them knew much about the historical precedent. I’m not a politician and I’m not a political scientist — I’m not sure why they did that vote. I do know, however, that there weren’t any hearings. This wasn’t done very deliberatively.

Last time around, 50 years ago, permanent daylight saving was sold to America as a panacea for the energy crisis — Nixon said that it would save 100,000 barrels of oil a day. Now, they’re not even talking about that, just how this would make life easier, with more daylight in the p.m. hours. They are saying, “You’ll be able to play sports at night, take the kids to the playground after school, go shopping.” They are selling it more as a social advantage rather than in response to a national security or energy crisis.

Right. But they’re ignoring or minimizing the effect that made people turn against it 50 years ago. In 1974, you had the extra hour of daylight in the afternoon, and people could take their kids to the park. All those afternoon benefits were still there in 1974, and of course there are benefits to having extra daylight in the afternoon. But the vast majority of people thought that the very negative of the dark mornings was not worth that extra hour of daylight in the late afternoon.

I see Wikipedia and others credit somebody named George Hudson from New Zealand, who was a bug collector — he collected insects — as the founder of daylight saving time.

I keep thinking I should correct that in Wikipedia. Benjamin Franklin first thought of the idea of waking up earlier to make better use of sunlight, but he didn’t think about moving the clock. George Hudson was the first to think of moving the clocks. However, his proposal never went anywhere. He proposed it in New Zealand, and a lot of people mocked it and thought it was a crazy idea, so nothing ever happened in New Zealand. So even though he sort of was the first one to think of that idea, it never went anywhere.

Whoever Hudson is, Benjamin Franklin was the one who came up with the adage of early to bed early and early to rise makes a person healthy, wealthy, and wise.

He didn’t do it for that reason. He just thought there would be more time in the evening to do things.

The person whose idea really led to the daylight saving time we have today worldwide is a British man named William Willett. Willett came after Hudson, but he was much more effective. He proposed a bill that eventually went to Parliament and became known all over Europe. Hudson’s proposal, as far as I know, wasn’t known anywhere outside of New Zealand.

When World War I began, because of the pressure of war, the Germans were the first country to put in daylight saving time, having heard of Willett’s proposal. And as soon as they did, the British did, too, as did almost every country on both sides of World War I — including, eventually, the US, when we got involved with World War I.

That’s when it started. It really came from William Willett. The idea was originally proposed by George Hudson, so he should get the credit for thinking of it. But nothing ever came from what he proposed. William Willett led to the daylight saving time that we have today.

In the Jewish community, the big issue everyone is talking about is prayer time. We pray in the morning, and we can’t

start praying before sunrise. So if someone

has to be at work in Manhattan at 9:00 in the morning and you can’t

start prayers before 8:15, 8:30, that really

interferes with it.

Right. I know that. I’m Jewish, even though I’m not Orthodox.

You have to remember that while sunrise in New York will be at about 8:30, in places like Detroit, Minneapolis, and Seattle the sun won’t rise until 9:00. So how are people going to do anything before work if the sun is rising at 9:00? It’s obviously going to be a big problem in parts of the country. Even in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, the sun is going to rise at 8:30 under this new proposal. So that’s pretty big.

A lot of the country is going to have a sunrise between 8:30 and 9:00, or maybe even later than that. I understand that’s a big impact on the Orthodox community.

On the other hand, this proposal takes away the scramble on the early winter Friday afternoons, when Shabbos can come

as early as 4:15. This proposal gives you an

extra hour. So there are pros and cons each way.

(Laughs) All I’ve heard from the Orthodox community are the cons. I haven’t heard anyone say what you just said. Obviously, nothing is 100% good or bad; there’s always some benefits.

I think, by the way, that there are other sects and some other religions who also pray after sunrise, and they have the same kind of problem.

Muslims will have a problem with Ramadan, because it adds an extra hour to the fast.

Right. When I’m asked about other issues besides people not going to work or school in the dark, I always mention the people who want to pray after sunrise and still have to go to work. It’s a major concern. I think that if the Orthodox community feels it’s a big negative, they should contact Congress — contact some Jewish congressmen or maybe just the congressmen who are on the committee which will hold the hearing on it.

From what I understand, it’s going to be considered in the House of Representatives by the Committee on Energy and Commerce. And I think it’s the subcommittee on consumer protection and commerce. They were the ones who contacted me before, so I’m assuming it’s the same people. If people want to give comments, it would be most effective to speak to people on that big committee or on the small subcommittee.

[The committee chairman is Rep. Frank Pallone (D-NJ), who is on the record as supporting making a single time year-round, though he has no opinion whether it should be standard time or daylight saving time — YD.]

As far as I know, there are going to be, maybe, a few months of hearings. I’ve heard they are going to do a lengthy analysis, but we’ll see.

Ultimately, I believe, this boils down to early risers versus night owls. The early risers want it and the night owls don’t.

Yes. Except that in the winter, most people are early risers by that definition. In the spring, summer, and fall, you have sunrises in a lot of places at 5:00 a.m. or 6:00 a.m., so if you add an hour to the sunrise, it wouldn’t affect most people — if the sun rose at 5:30 instead of 6:30, most people wouldn’t know the difference. But when you get into the winter, when sunrise in a lot of major cities will be at 9:00 a.m., and almost everybody going to school or work are going to go in the dark and cold, then everyone is an early riser in that distinction, right? Because they’re all rising before the sunrise.

That’s why it’s different in summer than winter. In the summer, there’s really no negative to a later sunrise, but in winter, it’s a big negative. That’s why, when I was involved with extending daylight saving time in 2005, we extended it to be eight months — essentially from the beginning of March to the end of October or a little bit into November. The reason was that that would be the most you can extend daylight saving time without starting to get the negative effects of the late sunrises.

So we now have eight months of daylight saving time and four months of standard time. And I personally think that’s not perfect, but that’s about as good as you could do.

To the people who complain about the time change and how they dislike it, I say that it’s no different than going from Chicago to New York or from London to Paris, when you lose an hour since you are in a different time zone. When people go to a different time zone, they often prepare for it by going to sleep a little earlier or taking it easy in the morning. With daylight saving time, a lot of people don’t even know the change is coming. They stay up late, and then the next morning they lose an hour of sleep so they’re groggy.

My proposal has been to have something like a public service campaign where you could tell people a few days in advance that daylight saving time is coming on Saturday night, and maybe you should try to get a little extra sleep that weekend to make it a more comfortable time change. That would minimize some of the problems they have. But again, it’s no different than going from Chicago to New York.

The newspapers will love the ad revenue.

Right. But that’s the kind of thing we do for other things — you know, don’t drink and drive on New Year’s Eve or things like that. We have those kinds of campaigns to try to get people to be more careful during problem times. It’s a relatively simple thing; it’s just that people don’t even know it’s coming, so they don’t make any adjustment for it.

Here in New York, they have these public service announcements during time changes about the traffic aspect — there are more traffic accidents at that time.

Did your research in this topic uncover anything interesting or any fascinating vignettes?

I have a whole book full of anecdotes and stories and interesting things that have happened over time.

Do you want to give a teaser for your book?

I could tell you, for example, that between the end of World War II and 1966, any city or town in the United States could have daylight saving time if it wanted to. So you wound up with situations where one town might have daylight saving time, the neighboring town wouldn’t, and a third neighboring town would have daylight saving time but with different starting and ending dates than the first town. So it got very confusing. People didn’t even know what the time was three towns away.

In Iowa, there were 23 different pairs of starting and ending dates. Let tell you one famous story of that time period — if you took a bus and rode the 35 miles from Moundsville, West Virginia, to Steubenville, Ohio, and the bus would stop in different towns along the way, you would have to change your watch seven times in 35 miles. Because some had daylight saving time and some didn’t. There was one time when Minneapolis had standard time and St. Paul had daylight saving time, and they are called the twin cities.

So there are a lot of interesting things that have happened in the history of daylight saving time. Those are some of them.

Doctor, let me ask you a question. Would you support combining all the time zones of the United States the way China has, and just have one uniform time zone across the country?

There are a lot of problems with that — there is a reason we have time zones around the world. China does it because all the power — economic and political — is in the east, in Beijing and Shanghai. I don’t think those people really care that much about the fact that the sun will rise at 10:00 a.m. or later in the western parts of China.

The thing about time zones is that when you talk to someone in a different city or you go to a different city, you know more or less what time business hours are, what time breakfast or lunch or dinner is. Those are the same all over the world, because of the time zone differences. If we didn’t have that and you contacted someone 1,000 miles away, you would have no idea if it was during business hours or in middle of the night. That’s the big benefit of having the time zones.

There are 24 time zones, one for each hour of the day.

You’ve done a lot of research in this obscure subject and even written

a book on it. Is this a hobby?

I have a PhD from MIT and I worked for several years at the US Department of Transportation doing research, and then I got involved with some other computer science things. I wound up being a pioneer in the area of artificial intelligence — completely separate from daylight saving time.

I got involved with daylight saving because I did work for three years on a detailed analysis of some of its technical pros and cons — energy uses and traffic accidents. But then there’s all these other aspects of daylight saving time as well; it makes people’s lives more pleasant or less pleasant. In the summer, spring, and fall, people like having an extra hour to go outdoors after work or after school. That’s why I think the current system is about as good as we could get. With all its flaws, it’s better than the alternatives.

One advantage of this is that whatever happens at the end, it will be bipartisan.

Well, let’s see. You may not have unanimity like in the Senate, but it will probably be bipartisan. I mean, for the people in favor of year-round daylight saving, it’s probably nothing to do with party, and the people who like the current system probably would not be party oriented. So I think it will be something that will be bipartisan, both the pros and the cons.

*****

A Brief History of Daylight Saving Time

From David Prerau’s book, Seize the Daylight

Benjamin Franklin, living in Paris, first conceived the notion of daylight saving time. He wrote that he was awakened early and was surprised that the sun was up, well before his usual noon rising. He humorously described how he checked the next two days and found that, yes, it actually did rise so early every day. Imagine, he said, how many candles could be saved if people awakened earlier, and he whimsically suggested firing cannons in each square at dawn “to wake the sluggards and open their eyes to their true interest.”

William Willett was a British builder who was up early for his pre-breakfast horseback ride in 1905. He lamented how few people were enjoying the “best part of a summer day”, and he came up with the idea of moving the clocks forward in summer to take advantage of the bright beautiful mornings and to give more light in the evening. He fought for years to introduce DST in Britain, but died never seeing his idea come to fruition.

During World War I, DST was first adopted in Germany, which was quickly followed by Britain and countries on both sides, and eventually, America. Daylight replaced artificial lighting and saved precious fuel for the war effort.

Post-World War I, American farmers fought and defeated urban dwellers and President Woodrow Wilson and got DST repealed, returning the country to “G-d’s Time.” Spotty and inconsistent use of daylight saving time in the United States and around the world caused problems, unusual incidents and, occasionally, tragedies. For example, disregard of a change to DST caused a major train wreck in France, killing two and injuring many.

When World War II began, all combatants on both sides quickly adopted DST to save vital energy resources for the war. The U.S. enacted FDR’s year-round DST law just 40 days after Pearl Harbor.

The chaos and high cost of non-uniform DST led to a law in 1966. There was widespread confusion when each locality could start and end DST as it desired. One year, 23 different pairs of DST start and end dates were used in Iowa alone. And on one West Virginia bus route, passengers had to change their watches seven times in 35 miles. The situation led to millions of dollars of costs to several industries, especially transportation and communications. Extra railroad timetables alone cost the equivalent today of over $12 million per year.

The Arab Oil Embargo of 1973 caused the first prolonged peacetime energy shortage in the United States, and the country quickly established year-round daylight saving time to save energy. The Department of Transportation found that with almost no cost as compared to other energy conservation options, DST reduced the national electrical load by over 1 percent, saving 3 million barrels of oil each month. After the crisis was over, the U.S. reverted to six months of DST, from May through October. This period as extended in 1986 to include April.

In Europe, after many years of non-uniformity of DST policy, and especially between the Continent and the United Kingdom, the European Union in 1996 adopted the summer time period that had been in use in the U.K. for many years: the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October.

William Willett would be happy to know that daylight saving time is now employed in about 70 countries around the world, including almost every major industrialized nation. It affects well over a billion people each year. Sunrises, sunsets, and day lengths of countries near the equator do not vary enough during the year to justify the use of DST, but even in those countries it is sometimes adopted, especially for energy conservation. It remains controversial in several locations, such as Queensland, Australia.