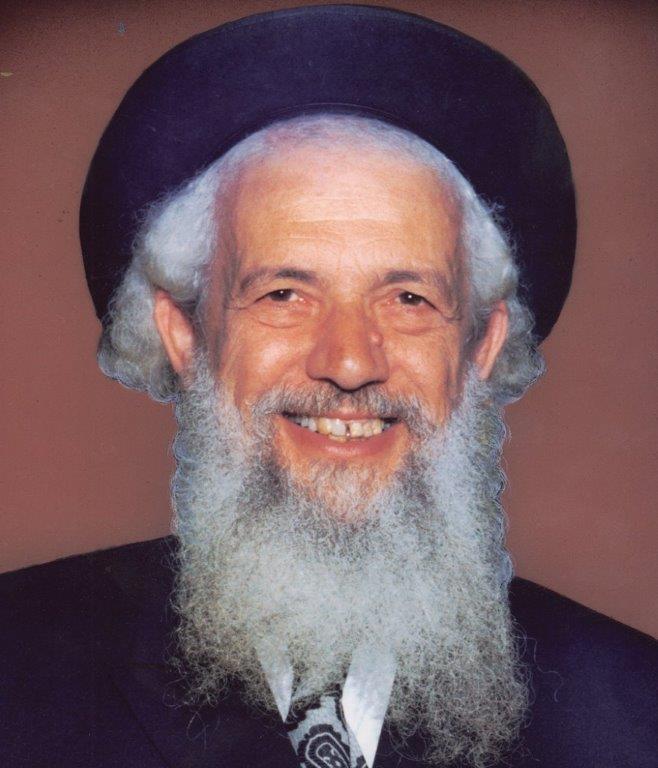

Rosh Yeshiva of Mesivta Torah Vodaas and Bais Medrash Elyon

Forty Years Since His Passing on 7 Tammuz, 1979. An Interview With His Close Talmid, Rabbi Nosson Scherman, General Editor at ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications

You wrote a seminal article in the Jewish Observer not long after Rav Schorr’s passing where you described him as “the first American gadol.” How did he become a gadol despite spending much of his formative years in America?

Rav Nosson Scherman: I would like to preface by saying that it was not I who described him as the first American gadol. Rav Aharon Kotler, rosh yeshiva of Lakewood, was the one who actually called Rav Schorr “the first American gadol.” Rav Henoch Cohen, who served as head of Chinuch Atzmai’s operations in America, told me that he heard Rav Aharon describe Rav Schorr in those terms.

As far as his earlier influences, before I get to the impact of Mesivta Torah Vodaas and Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, or Mr. Mendlowitz, as he insisted on being called, it is important to note that Rav Schorr came from a family of staunch Sadigura chassidim. His parents were among the special Yidden who came to the United States during the first quarter of the last century and, despite tremendous nisyonos, remained ehrliche Yidden and raised G-d-fearing generations… a feat that could not be taken for granted in those days, even for talmidei chachomim.

Even from a young age, the fire of Torah burned within Rav Schorr. When he was a teenager, he holed himself up in his parent’s attic, where he learned for some two years with great hasmodah. His mother would bring his meals up to the attic, so as not to interrupt his learning.

Without a doubt, though, the mesivta was the primary generator of his ruchniyus as a bochur, and Rav Mendlowitz was probably the primary early influence on him.

How so?

Reb Shraga Feivel introduced him to chassidishe machshovah seforim. He opened Rav Schorr’s fertile brain to the world of the Maharal, the Sefas Emes and Rav Tzadok HaKohein. Rav Schorr particularly connected to the profundity of those seforim and, in his brilliance, was able to forge a path in his own avodas Hashem based on the teachings of these seforim.

So, due to Rav Shraga Feivel, Rav Schorr became a great boki in chassidishe seforim?

Yes. His oldest son, Rav Yitzchok Meir Schorr, told me that his father knew all chassidishe seforim but ultimately, he would always return to the Sefas Emes. The Sefas Emes became his primary handbook and guide. The Gerrer Rebbe, the Bais Yisroel, said he was one of the greatest experts in Sefas Emes in the generation.

Who were his rabbeim in Toras Haniglah, in lomdus?

Firstly, you must understand that Rav Schorr was an absolute genius, and when he came to Torah Vodaas, he was already, in many ways, a “fartige lamdan.” Still, I am certain that his rabbeim in Torah Vodaas – including Rav Dovid Leibowitz and then Rav Shlomo Heiman – undoubtedly had a tremendous influence on him.

In addition, Rav Aharon Kotler had a colossal impact on him. Rav Aharon came to America in the 1930s to raise funds for the Kletzker Yeshiva – as virtually all the roshei yeshivah were forced to do – and that is when Rav Schorr got to know him. He was struck not only by Rav Aharon’s profound genius, but also by his tangible, burning love of Torah.

In the 1930s, when Rav Schorr was still a bochur, Reb Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz appointed him as a maggid shiur in the yeshiva. He gave shiur for a number of years, during which he married Rebbetzin Shifra, a daughter of Rav Nechemiah Isbee, a Gerrer chossid living in Detroit.

After his wedding, Rav Schorr decided that he wanted to further his learning. He took a leave of absence from his position as a maggid shiur, and, together with his rebbetzin, journeyed overseas to learn under Rav Aharon Kotler in Kletzk. He saw Rav Aharon’s derech halimud and profound love of Torah as attributes he sought to inculcate into his own avodas Hashem. Towards that goal, he left the comforts of America, along with his job security, for the spartan conditions of pre-war Poland so that he could learn Torah from Rav Aharon. Rav Boruch Kaplan, who had returned to America after learning in Europe, took over Rav Schorr’s shiur.

Did Rav Schorr ever tell you about his years of learning in Kletzk?

In general, he didn’t talk much about himself, but Rav Yitzchok Meir Schorr told me that Rav Schorr’s parents had sent mattresses from America for them to sleep on. When the couple arrived in Kletzk, however, they learned that Rav Aharon and his rebbetzin were so poor that they slept on simple straw mattresses. Rav Schorr did not feel that he could sleep on “fancy” American mattresses while the rosh yeshiva and rebbetzin did not even own mattresses, so the Schorrs gave their mattresses to the rosh yeshiva.

These middos of altruism and selflessness were part of his essence?

Absolutely! Rav Schorr was a very unselfish person. He wasn’t at all busy with himself. I remember, in his later years, when he was one of the leading roshei yeshiva in America, he would address the Agudah Convention. He would tell Rabbi Moshe Sherer, “I don’t need any prime speaking spots. Whenever you want me to speak, I am ready.”

He had no airs about himself, and was completely accessible, talking to talmidim, interesting himself in their lives and their problems, like a big brother.

(Incidentally, while in Kletzk, Rav Schorr became close with Rav Shneur Kotler – who was a few years younger – and the two developed a close relationship. Someone told me that it was Rav Schorr who introduced Rav Shneur to the sefer Sefas Emes in Kletzk. Rav Shneur was profoundly impacted by the sefer, and quoted it extensively in his shmuessen.)

Speaking about talmidim, what shiur did he give and how did he influence the talmidim?

Rav Schorr became a maggid shiur while he was in his twenties – not much older than his talmidim. The fact that he was raised in America was also a quality that empowered him to have an influence on talmidim in ways that many European roshei yeshiva couldn’t.

Initially, Rav Schorr was a regular maggid shiur. When Rav Shlomo Heiman took ill, however, Rav Shraga Feivel asked Rav Schorr to say the rosh yeshiva’s shiur.

[When Rav Shlomo Heiman fell ill and stopped saying the shiur, Rav Shraga Feivel asked Rav Reuven Grozovsky, then rosh yeshiva of Kaminetz, who had recently arrived in America, to give the highest shiur in Rav Shlomo’s place, but Rav Reuven adamantly refused. As long as Rav Shlomo was alive, he felt that he couldn’t take over the shiur, since he might inadvertently cause chalishas hadaas to Rav Shlomo, and thus Rav Schorr was temporarily appointed maggid shiur. After Rav Shlomo’s petirah, Rav Reuven became rosh yeshiva and delivered the highest shiur, and Rav Schorr returned to his post as maggid shiur in second year bais medrash.]

Why did he have such an impact on his talmidim?

Aside from his brilliance as a maggid shiur and his ability to break down difficult concepts in such comprehensible ways, you have to understand that for us Americans, he was in some ways one of us. Yes, he only gave the shiur in Yiddish, but when one of us came to talk to him in learning, if they were more comfortable talking in English, he spoke in English.

In general, he was a tall, handsome man, who was very friendly and had a remarkable sense of often self-deprecating humor. We Americans connected with him. From Rav Schorr, we saw that it was possible to be raised here in America and still become a gaon and lamdan like the European roshei yeshiva. Such a thing had been unheard of until then. In essence, Rav Schorr was unique among the rabbeim and roshei yeshiva in Torah Vodaas, and his role in shaping the worldview of the talmidim cannot be overstated.

Another very important component that showed true greatness was his middos. He was, of course, brilliant, but he had time for everyone. He never showed the impatience of an ilui. He was able to “come down” to anyone’s level, and he never spoke disparagingly about those who had wronged him. He embodied the middos of restraint and altruism so praised by Chazal. Rabbi Sherer once told me that Rav Schorr embodied the sefer Orchos Tzaddikim.

How did Rav Schorr become involved in Bais Medrash Elyon, and ultimately, the rosh yeshiva?

Let me give your readers a bit of a history lesson regarding Mesivta Torah Vodaas and Bais Medrash Elyon, the “post-graduate” bais medrash-level yeshiva founded by Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz in the 1940s.

Rav Schorr started out as a maggid shiur working under Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz. As long as Rav Mendlowitz was alive, Rav Schorr’s primary responsibility was delivering the shiur at the mesivta. Before Reb Shraga Feivel’s passing, he appointed Rav Yaakov Kamenetzky and Rav Schorr as co-menahelim, and he gave Rav Schorr what was akin to a tzavaah. He told him that part of his mission was to preserve “dos pintele chassidus,” that spark of chassidus he had infused in the yeshiva.

After Rav Reuven Grozovsky’s petirah, Rav Schorr’s duties at Bais Medrash Elyon in Monsey increased. At that point, he also began to give shiurim, and was also forced to assume much of the financial burden of the yeshiva and kollel. It pained him that in his later years, he was not able to spend as much time learning with and teaching talmidim as he had in earlier years.

As a rebbi, what was his relationship with his talmidim?

He wasn’t necessarily the kind of rebbi who showed overt affection, but we knew that he loved us and cared for us as a father does for a son.

How so?

Let me share a story. When I graduated high school, my parents, like most of the good, European-raised parents of that era, were convinced that if I didn’t go to college, I would starve to death. I deeply wanted to continue learning, but my parents felt that if I wouldn’t go to college, they would be shirking their responsibilities as parents.

One afternoon, toward the end of my 12th-grade year, or maybe when I was in the Bais Medrash, my parents, who owned a grocery store in Newark, New Jersey, were in their store when a distinguished gentleman entered. He introduced himself as Louis Septimus, chairman of the board of Mesivta Torah Vodaas.

Septimus was a high-powered, very successful accountant. He told my parents that he happened to be in Newark on business, and felt compelled to pop in just to tell them how impressed he was with their son, Nosson. “I hear your son is one of the finest talmidim in the yeshiva,” Mr. Septimus said, and recommended that I stay in the yeshiva because “it would be a pity to stop his learning at this juncture.”

That visit had a transformative impact on my parents. If the chairman of the board of the yeshiva and a very successful accountant – who had himself “made it” in America – was saying that I should remain in learning, I would probably also not starve!

Boruch Hashem, my parents let me stay, go on to Bais Medrash Elyon and later to kollel – but that wasn’t the end of the story. After Rav Schorr was niftar, Mr. Septimus told me the rest of the story. Decades earlier, when he had paid a visit to my parents’ store in Newark, it was not because he “happened” to be there on business. In fact, Rav Schorr had approached him, saying “If I go to the Schermans and tell them what a pity it would be for their son to leave the yeshiva, they’ll say, ‘Well, of course he is saying that. He is the rosh yeshiva. His business is to retain good talmidim.’ If, however, a successful businessman comes and tells it to them, that will have a completely different impact.”

He was clearly right!

Was it because he had a special relationship with you? Did he do these things for other talmidim as well?

He was a father figure to many talmidim. I remember when a friend of mine lost his father. Not long thereafter, he became engaged. Who went with him to buy the ring? Who accompanied him to buy a suit for the chasuna? Rav Schorr himself – just like a father would take a son.

Another story: I mentioned that finances were officially not his responsibility, but when, for various reasons, there was no money to pay the kollel yungerleit and the meager checks were bouncing, Rav Schorr would cash the checks for the yungerleit. Somehow, he raised or borrowed the money, and he never deposited the checks. After his passing, a whole pile of uncashed kollel checks was found in his possession.

We briefly touched upon the fact that in those years, most parents – even fine, upstanding ehrliche parents – insisted that their sons attend college, fearing that they would otherwise not be able to sustain their families. How did Rav Schorr navigate that quandary?

He tried his utmost to influence bochurim to stay in learning with varied degrees of success. As the years moved on, it became easier.

Nevertheless, in the event that a bochur went to college, he still remained a beloved talmid and Rav Schorr would work with him to ensure that despite no longer being between the walls of the yeshiva, he should continue to devote his efforts to progressing in limud haTorah and yiras shomayim. Today, there is a demarcation line between these two groups – those that didn’t go to college, and those who did. That didn’t exist in those days. In the mesivta, there were never two separate groups – they were mixed together, and the roshei yeshiva treated them all as beloved talmidim.

How would you encapsulate Rav Schorr’s role in the then-fledgling Torah community of the United States?

His was a seminal role in a number of ways. Already in the early 1930s, Rav Schorr was the default rov of the Tzeirei Agudas Yisroel shul at 616 Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg. That shul was perhaps the engine responsible for keeping Yiddishkeit alive among a younger generation in the pre-Holocaust era, before the roshei yeshiva and chassidishe rebbes arrived after the war.

It was Rav Schorr who was the mentor of Mike Tress and other heroic young American Agudah youth of that era, who went against the tide of American materialism and assimilation. It was his guidance and love that helped direct and sustain their Yiddishkeit and heroic hatzolah work.

In the yeshiva, I would say that Rav Schorr could be classified as the bridge between Europe and America. He was the role model that the American bnei Torah could aspire to be. Raised right in Williamsburg, he reached gadlus b’Torah on par with the European roshei yeshiva.

Another important component that made his hashpaah on us so great was the fact that, combined with his greatness and gaonus in Torah, he was very me’urav im habriyos – he was friendly to everyone, he was accessible and he had no airs about him. He was an ilui, but had the patience to tolerate all types of people with different opinions and approaches.

Talmidim liked him. Even those who were not deep enough or did not have enough knowledge to appreciate his gaonus in Torah were still connected to him, because he connected with them and valued them for the good qualities they had. That said, however, Rav Schorr’s own personality was not the kind to force people to do things. He taught by example. He wasn’t a fiery person who pushed and cajoled others to do this or that. Rather, his hashpaah resonated through his own personal example. To his close talmidim, he was a guide who could influence by personal example and gentle persuasion.

Nevertheless, he did advise those who were truly close to him in a stronger manner. In 1959, when I got married, I was not planning on learning in kollel, but Rav Schorr twisted my arm and pushed me to stay in Bais Medrash Elyon. I am eternally grateful to him for this, because it changed the trajectory of my life and family.

You spoke about the fact that Rav Schorr was a gaon in the machshovah of chassidus. How did that manifest itself in the mesivta?

In Torah Vodaas, Rav Schorr gave shiurim and would periodically give shmuessen. He gave a daily Chumash shiur from 9:00-9:30 a.m., which had a phenomenal combination of meforshim.

I would like to share some more history. In the early years of Bais Medrash Elyon, as I mentioned, Rav Schorr didn’t have much to do with the yeshiva. Rav Reuven Grozovsky was the rosh yeshiva, and the day-to-day running of the yeshiva was done by the mashgiach, Rav Yisroel Chaim Kaplan. After Rav Reuven’s petirah in the late 1950s, Rav Schorr began coming to Monsey every week, where he gave a shiur on the masechta. He also gave his unique maamarim based on the works of the Sefas Emes, Rav Tzadok and others. His power of chiddush and his genius in these areas were perhaps unparalleled.

Did the bochurim and yungerleit appreciate his approach?

Absolutely! Bais Medrash Elyon was a unique institution, combining tremendous hasmodah, lomdus and analytical learning that the roshei yeshiva from Lita brought with them, together with the fire of chassidus, dedication to purity in avodas Hashem, and the depth of chassidishe machshovah, all rolled into one yeshiva.

In those days, the clear lines between different communities did not exist. We had misnagdim and chassidim – with a lot in between – in the same bais medrash, and we all got along and learned together. Paths between one group and another were not as clearly drawn as they are today. Bais Medrash Elyon was a unique family of talmidei chachomim and ovdei Hashem who synthesized a number of derachim in avodas Hashem. Rav Schorr himself was the prototype of this synthesis, and his shiurim and shmuessen reflected that.

The beautiful, deep maamarim in the sefer Ohr Gedalyahu are from the maamarim he gave?

Yes. Unfortunately, they were only from the last two or three years of his life. Today’s generation, where everything is recorded and videoed, will have a hard time comprehending this, but for decades, no one thought of bringing a tape recorder to record his shmuessen.

He was a mayan hamisgaber, and every year, he said new Torah, deep Torah, full of wondrous chiddushim. The maamarim in Ohr Gedalyahu were recorded during his last years, when he was somewhat slowing down. In his earlier years, his power of chiddush and brilliance were possibly even stronger. Still, Ohr Gedalyahu has become a classic. Imagine if we would have recorded all of his shmuessen that he had delivered in the preceding decades!

Let me conclude by asking, what do you think Rav Schorr would say if he came today and observed the frum community 40 years later?

I think that he would be very proud of how far we have come, how much the Torah community has grown and how limud haTorah occupies a central place in our collective congregations and communities in America, infinitely more than it did in his lifetime.

That said, I think he would have also been very concerned by some of the ideals that have infiltrated into our community. For example, the level of gashmiyus, the amount of material pleasure, would have been foreign and perhaps even an anathema to him.

You have to know how simply he himself lived to understand how little importance he attached to the material. He was never paid much – his salary was shockingly low – but he never needed anything either.

Any final thoughts?

He was our rebbi and he taught us and guided us. His very essence as a gaon, masmid, and baal machshovah broadened our horizons, enabling us to overcome the many challenges facing young bnei Torah in our times.

Because he passed away so long ago and at a relatively young age, his seminal role in being one of the few great roshei yeshiva who transformed our world into a Torah world has become somewhat forgotten. He was not only one of the great gaonim and teachers, but in his quiet way, he was one of the great builders of the American Torah community.