The process began when Rav Aharon was a young bochur in the Veitzen Yeshiva, where he established groups of bochurim and baalei batim who wanted to devote themselves to spiritual improvement. This led to the founding of Kehillas Yirei Hashem in Satmar in 1921, comprised of young men who dedicated their whole lives to Torah and tefillah.

At about that time, the Bluzhover Rebbe, Rav Yehoshua Spira, installed the new Rebbe by publicly seating Rav Aharon on his own chair, placing his hand on his head, and announcing:

“I hereby give you the semichah I received from my father to lead Klal Yisroel, and I bequeath you with the power to bless Yidden. Know that I am the fourth in line to get semichah from the holy Baal Shem Tov. He gave semichah to the holy Maggid, the Maggid gave semichah to the Chozeh, the Chozeh gave semichah to the Sanzer Rebbe, and he gave semichah to my father and to myself.”

In 1928, Rav Aharon moved to Eretz Yisroel and established his beis medrash at the end of Meah Shearim. Due to his great stress on answering amen, he named his group Shomer Emunim. The following year, due to the Arab pogroms and ill health, he returned to Satmar for ten years and reorganized his old chaburah.

Sad at the distance from their leader, many followers back in Eretz Yisroel wrote and asked whether they should leave Eretz Yisroel to join him in Europe. His reply was that they should stay where they were.

“No one should come here,” he said. “I see that this rasha [Hitler] will make a war so terrible that we will be fortunate if one person from a town and two from a family survives the destruction.”

This was during the 1930s.

During these years, Rav Avrohom Chaim was growing from a child into a young bochur.

Someone who knew the rebbe from those days once told his chassidim, “Do you know who your rebbe is? When we learnt in cheder, he brought food from home every day. But he never ate it. Instead, he gave it to poor classmates who came with nothing. On one occasion when he came to cheder with new shoes, he noticed a boy whose shoes were torn. Without a second thought, he removed his new shoes and took the boys old ones in exchange.” Even in those days, Rav Avrohom Chaim was a friend of the broken hearted and poor.

As he got older he restricted his enjoyment of earthly pleasures and eventually, his regimen involved rising at two and learning until dawn.

“Laigen zich shlofen iz a megushamdiker zach,” he used to say. “To lie down and sleep is a megusham activity.”

In later years he ate little. He said that he never tasted chocolate or sweets his whole life and complained that by indulging children with such delicacies, people were developing their physical side at the expense of their spirituality.

In later years, whenever he was hungry or tired, specifically at such times, he would overcome his physical yearnings like a lion and continue serving the Creator. On Shabbos he never slept at all, in order to utilize every moment of the holy day.

After the outbreak of War World 2, it took time to procure the necessary legal emigration papers, and Rav Aharon and his family left Europe on the last legal boat to sail from Romania, shortly before Sukkos. By Simchas Torah, the ship was caught in a violent storm. Rav Aharon refused to allow this to disturb his hakofos and danced with no less dveikus and joy than if he was on dry land.

“This man is an angel!” the captain declared.

Realizing Rav Aharon’s greatness, the captain offered him a comfortable cabin, but the rebbe wouldn’t hear of it and remained below with the sacks and crates of the ship’s hold.

“Millions of Jews are jealous that we have escaped, and we should live like princes?” he explained.

Passing through the Gibraltar Straits, a magnificent vista unfolded, the rock of Gibraltor looming on the right and fronted by the mist shrouded coast of Africa on the left.

Taking his son Rav Avrohom Chaim aside, Rav Aharon said to him, “We now have the opportunity to see something we’ll never see again our whole lives. But instead, we will sit and learn instead of indulging in pleasure.”

In later years, Rav Avrohom Chaim loved showing people the small masseches Brochos he and his father studied for an hour and a half as the boat passed through the scenic strait, and would conclude with the admonishment, “You don’t always have to see everything!”

THERE WILL ALWAYS BE BREAD

Rav Aharon gave his son semichah in 1945 when he was 21-years-old. By then, many important families were anxious to take Rav Avrohom Chaim as a son-in-law. His father chose Rebbetzin Basya Chaya, the oldest daughter of Rav Mordechai of Zevhil. When Rav Mordechai went to ask his father, Rav Shlomo of Zevhil, what he thought of the various offers made for his daughter, Rav Shlomo immersed himself in a mikveh,as he always did before giving advice, and and said his granddaughter should be told as follows:

“One of the interested families will have an abundance of money, the second an abundance of honor, but by the third [Rav Avrohom Chaim] you will find an abundance of yiras Shomayim.”

When the 15-year-old girl heard the answer she asked her grandfather, “But what will we eat if we fall on hard times?”

To which he answered, “Bread you will never lack.”

Rav Avrohom Chaim testified that indeed, even during the siege of Yerushalayim in 1948 when food was scarce, he always had enough to give to others.

The wedding was one of the largest held in Yerushalayim of those days. As a wedding gift, Rav Avrohom Chaim’s in-laws gave him two items, a besomim box made from melted down matbe’os brochah [coins given by a rebbe as a blessing] from the Baal Shem Tov and his talmidim, and a soup tureen cover from Rav Mordechai of Neshchiz.

After the passing of Rav Aharon in 1947 at 65, Rav Avrohom Chaim inherited his father’s beis medrash, while his brother-in-law, Rav Mordechai Goldman, together with many of the chassidim, separated and founded the Toldos Aharon beis medrash.

Shortly afterwards, Rav Avrohom Chaim began saving children from Zionism. Many frum children and teenagers from Europe were being torn from their heritage by being sent to non-religious kibbutzim and settlements.

It started with a train ride. As a young leader, he was traveling to Tel Aviv in 1949 when a stranger said to him, “How can you sit and learn and do nothing? Do you know that there are new crematoriums where they are burning Jewish souls in kibbutzim and turn them into mechalelei Shabbos?”

Immediately, Rav Avrohom Chaim told the person traveling with him, “We’re going to Chaifa instead of Tel Aviv.” The first immigrant camps were sited close to the Chaifa docks. He feared no one. When guards once threatened to shoot him he declared, “Shoot! I’m not afraid.”

Cutting through barbed wire fences, he sneaked in and offered youngsters the chance to come with him to Yerushalayim, saving thousands. Some of them studied in other yeshivos,and others studied in a yeshiva of his own which he opened at the time.

These activities required capital. The Chazon Ish gave him five hundred lirot, a huge sum for those times, and to this day a plaque hangs in the Shomer Emunim office in commemoration of the godol’sdonation. The Rebbe told the Brisker Rov that Zionists were burning the Torah and encouraged people to go and save whomever he could. This was the inspiration for the founding of Pe’ilim and other such organizations. He was like a father to the people he saved, and many became his followers. Nowadays, most of them are proud grandparents and great-grandparents of Torah Jews.

In the 60’s, Rav Avrohom Chaim began building his Shomer Emunim neighborhood, located between Meah Shearim and Beis Yisroel. Money was scarce and the government was tight fisted, but Rav Avrohom Chaim had the power of persuasion. He was a man of truth and afraid of nothing. He said what needed to be said and could not abide falsehood.

Against people’s advice, he personally approached the President of the national bank, a person who was tough as nails and not likely to be influenced by rhetoric.

“What do you want?” the president asked.

Standing before him in his opulent office the Rebbe said, “I want to tell you a story. In Russia everyone was equal but poor. One poor man accepted that until he happened to wander into a neighborhood inhabited by the privileged government class. Naively he asked himself, ‘Why are we living in squalor while our rulers live in luxury?’”

“Jews from Nazi camps are living in damp basements with no electricity,” the Rebbe continued. “I want to build them beautiful apartments and you sit here in an opulent hall and tell me there is no money. Are you not ashamed of yourself!”

Miraculously, the president provided him with 50,000 lirot, inspiring someone to remark, “There are some things only Rebbes can do!”

Like his father, the Rebbe was non-affiliated in politics.

“Every tzaddik is like a masechta of the Shas,” his father used to say. “If a person learns Maseches Shabbos, does it mean that Maseches Brochos becomes jealous? If a chassid becomes attached to a tzaddik according to Hashem’s guidance and according to the root of his soul, can one have any objections?”

Likewise, the Rebbe admonished, “Don’t get mixed into politics; always be neutral.”

At the dedication of his new housing project, leaders and rabbonim of a variety of camps sat at the podium in harmony, united by the Rebbe’s harmonious friendship.

Rav Avrohom Chaim once said: “The only person who should be a kanai, is someone who does not enjoy being a kanai.”

He also noticed everything going on around him and acted on his observations. When someone came to him for his son’s chalakah, the Rebbe noticed the boy’s shoe was torn.

“Go and buy shoes for all the children of that family,” he instructed one of his confidants, “and don’t let them know where the money came from.”

He followed the news with great interest, not out of idle curiousity, but out of his great yearning for bi’as Hamoshiach. He correlated world events with his immense and deep knowledge of Chazal and kabbalah, confidently identifying which stage of the redemption we were holding at and predicting what the future held tomorrow.

Like his father, Rav Aharon, the Rebbe’s main goals too were to serve Hashem through prayer and tzni’us.

During the last winter of his life, Rav Aharon had written that prayer was foremost for him from his earliest days.

“From my childhood,” he wrote, “Hashem placed within me a burning fire to publicize the importance of prayer… I looked around and saw that this great thing all the worlds rest upon is trampled into the dust and ashes… Nothing can increase one’s spiritual knowledge and understanding as much as the labor of prayer.”

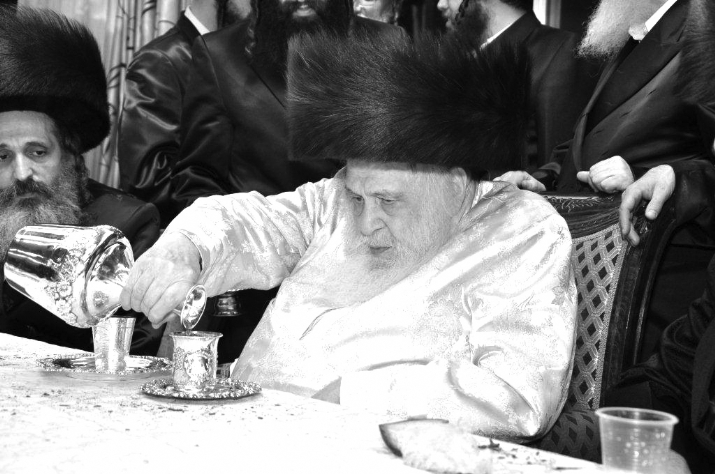

Rav Avrohom Chaim was a great baal tefillah. He was known for his melodious, powerful davening, singing the same nigunim his father once used during davening. His tefillos soared to the heavens. On Rosh Hashanah,when he declared, ve’ata Hu melech chai vekayam, people heard him blocks away. Weekday tefillos at Shomer Emunim can last for hours.

A FOUNTAIN OF ADVICE AND BLESSING

The Rebbe was a known baal eitzah and baal mofeis.

When someone once fell ill with cancer, the Rebbe blessed him and he recovered. Two years later he had a relapse. This time, when the man’s wife phoned the Rebbe for help he replied, “Not every day is market day in Brod.”

The sick person cried to the Rebbe, saying he was still a young man.

“I am marrying off a granddaughter in a few weeks,” said the Rebbe. “Come to the wedding and I’ll work a yeshu’ah for you during the mitzvah tantz.”

The man flew in from the USA, very weak by this time. After the mitzvah tantz, Rav Avrohom Chaim blessed him with an unusual twist of expression, saying, “I accept you upon my shoulders.”

When the man passed away just days after the Rebbe’s passing, people understood what his strange words had signified.

Two years ago on Chanukah, the Rebbe delayed lighting the candles for an hour-and-a-half.

“I am busy looking after the son of my chossid so and so,” he explained, mentioning the name of a follower in Monsey.

Afterwards, someone phoned the chassid to find out what the Rebbe had meant.

“This afternoon,” the chossid’s wife told him, “I forgot my son was coming by bus from cheder, and he was alone next to a busy highway for an hour-and-a-half until I remembered.”

For that hour-and-a-half, the Rebbe was looking after the boy.

During his lifetime, the Rebbe published his father’s seforim, including Shomer Emunim, Taharas Hakodesh, and Shulchan Hatahor. In 1976 he moved to Bnei Brak where he spent most of the year, founding a beis medrash, talmud Torah and yeshiva. For the Yomim Tovim of Tishrei and Shavuos, he would return to Meah Shearim, where he was joined by his followers from all over Eretz Yisroel and overseas.

In 2004, Shomer Emunimfounded a beis medrash in Ashdod, where Rav Avrohom Chaim’s son, Rav Aharon serves as Rav, and this was followed in 2008 by the opening of a beis medrash in Beit Shemesh.

HIS PASSING

Some months ago, Rav Avrohom Chaim collapsed in his beis medrash in Yerushalayim and was rushed to intensive care in the Bikur Cholim Hospital. After a few hours, he opened his eyes and asked for tefillin. After his health stabilized he moved to the Sheba Hospital near Tel Aviv for convalesence. But after six weeks, his condition worsened. Last Thursday night, noticing that his end was near, a faithful attendant gave him a glass of milk and he fulfilled the custom of tzaddikim to recite shehakol before one’s passing, and with the recital of Keri’as Shema and vidui,he passed away.

The next morning, his funeral began at his beis medrash in Bnei Brak, attended by a huge crowd; hundreds of cars and busses continued with the niftar to Yerushalayim, where he was interred next to his father on Har Hazeisim. Hundreds left kvittelson the kever that the tzaddik should be ameilitz yosher on high as he was during his lifetime.

He is survived by his four sons and his four sons-in-law, who are rebbes of the dynasties of Madesh, Radoshitz, Neshchiz, and Sambor, in addition to his grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Yehi zichro boruch.