We are a nation of faith. As maaminim bnei maaminim, we have a legacy of belief and are in constant struggle with those who would destroy the delicate fabric of our emunah and bitachon. It is no coincidence that gedolim, from Rav Saadya Gaon to the Chazon Ish, have written entire seforim to preserve and defend every detail of our theology. Yet, perhaps the most misunderstood and misinterpreted aspect of emunah is emunas chachomim, trust and acceptance of the word of our Torah leaders. The Chazon Ish (Sefer Emunah Ubitachon 3:30) writes that there is a special yeitzer hara assigned to make us cynical about our current gedolim. “We claim,” he asserts, “that we would most certainly listen to daas Torah if only…we had the Rambam, the Vilna Gaon, the Baal Shem Tov, the Chofetz Chaim etc. In short, anyone no longer alive and from a previous generation.”

This week, with the advent of Parshas Parah, we have a unique opportunity to rededicate ourselves to emunas chachomim and those who bear the imprimatur of daas Torah. To be sure, it is sometimes difficult to establish who these chachomim are and what they are trying to teach us, but the parah adumah provides us with a singular perspective on these matters. The parah adumah is the ultimate inscrutable halachah. Even Shlomo Hamelech could not fathom its seemingly illogical contradictions and enigmas. Yet, Moshe Rabbeinu did understand its system of polarities and contrariety (Sheim MiShmuel, Chukas 5672). The Torah teaches that after the miracle of Krias Yam Suf, “they believed in Hashem and Moshe His servant.” The Sefas Emes (Pesach 5639) explains that this is the source of our mandate of emunas chachomim – to believe in and trust the sages of every generation.

The Alter of Kelm (Chochmah Umussar 1:21) adds that the great proof of this mandate is the parah adumah. Human logic would normally dictate that no religion could command a nation to fulfill such a nearly impossible task. To find a completely red cow, which does not even have two black hairs, should be so inconceivable and unimaginable that the human intellect would reject the commandment. And yet, not only is it one of the 613 commandments, but it is the paradigm of all loyalty to the word of our Torah leaders, whether or not we understand the reasons why.

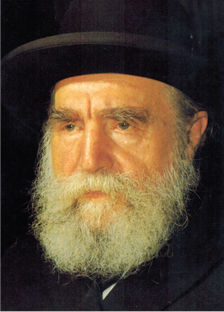

Which brings us to Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l. Last week, we commemorated his 30th yahrtzeit on Taanis Esther, the 13th of Adar. Known as the posek hador, the halachic decisor of the generation, he was also one of the best examples of why we should adhere to every bit of advice, guidance and counsel the gedolim grant us. In addition to all we have already heard, this year we have been granted a gift to live by. A new volume in the Masores Moshe series, published just in time for this milestone, offers a treasure of Rav Moshe’s wisdom, sagacity and ultimately daas Torah. We are proud to offer, with the permission of the publisher, some of these invaluable life lessons from our rebbi and moreh derech.

Rav Moshe was told that a certain evil person, who had married a second wife against the dictates of the Torah (cheirem d’Rabbeinu Gershom) might agree to finally give his wife a get if the rosh yeshiva would write a letter attesting to his always having been an honorable man. Rav Moshe initially responded, based upon the famous ruling of the Maharshal (Yam Shel Shlomo, Bava Kama 4:9) that one is forbidden from lying in a Torah matter, even if the result would be someone’s death. Rav Moshe stressed that when the sanctity and preservation of the purity of halachah are at stake, absolutely no dishonesty is allowed. In the end, after carefully weighing many options, Rav Moshe agreed to write the following ambiguous language: “I am happy to hear that you have agreed to divorce your wife. Everyone should give you the respect due a Torah scholar according to Torah law.” He explained that those with mental acumen would understand the nuances of his letter. Since this might help obtain a get for the woman and the testimonial did not falsify the Torah, it was permissible (pages 375-376).

On the other hand, when a woman asked why women were forbidden from dancing with the Torah on Simchas Torah, Rav Moshe was unequivocal about the prohibition. Yet, he found a way of presenting the fact that not everyone was permitted to dance with the Torah in an unthreatening and universal manner. He pointed out that at the Simchas Bais Hashoeivah on Sukkos in the time of Chazal, only the sages actually danced (Sukkah 51a). He further clarified that in most shuls, even amongst the men, only a minority of the people dance with the Torah. This proves, he explained, that the joy inherent in Simchas Torah is not necessarily associated with dancing with the Torah, but flows from the entire atmosphere and experience. Although some claimed that Rav Moshe did not have to even answer this query, he felt that he must consider the question carefully and respond, since the woman was serious and sincere (page 378).

On the perennial questions of chinuch, Rav Moshe was incredibly compassionate toward the unfortunate, but strong and unyielding against incursions into traditional methods of teaching Torah. He felt that it was “madness” to teach Torah to English-speaking students in Ivrit, Modern Hebrew. Since the goal of Torah study is to understand the maximum possible material with the most depth, adding another language barrier was simply illogical, and he expressed this to the school’s principal. However, when it came to children with major learning disabilities, to the point of seeming “abnormal,” he ruled that it was preferable to keep them in a special class in a regular school rather than in a school serving an entire population of challenged children. The only reason for this decision was so that the disabled children would not feel estranged and “abnormal” if not absolutely necessary.

Although the rosh yeshiva had ruled that a married man was allowed to teach in a co-ed high school, while it was definitely forbidden to found such a school, he concluded that under no circumstances should he teach Gemara to girls. His advice was that if the teacher had to teach in this school for his parnassah, he should request a lower grade, where the Gemara issue was not relevant. Again, watch for the incredible nuances and subtle decision-making, taking into consideration individual needs and the far-reaching ramifications of a seemingly minor act upon eternal values and perceptions (page 382). Nevertheless, Rav Moshe cautioned (page 384) against excessive harshness and constant chastisement of children’s behavior. He stressed that to be the successful recipient of mussar, one must have a lofty soul and broad intellectual capacity. For most people, the rosh yeshiva warned, softness and a moderate approach are necessary.

Rav Moshe’s nuanced approach can be seen in his advice to a bochur whose parents felt that he was becoming extreme and fanatical because of his yeshiva. He appeared to them to have become anti-social and in general dysfunctional. They wanted him to begin studying secular studies so that he would be able to get a job someday and also to stabilize his apparent fanaticism. Rav Moshe assured the young man that he should not study anything secular, but should begin speaking to people about everyday subjects, not just Torah. He explained that it was important for a ben Torah not to appear to be a batlan, someone unsuitable for normal life. In addition, the rosh yeshiva stressed that acting now like a batlan would surely lead to bittul Torah later in life. He counseled the young man to attend a regular summer camp, not a full-time learning yeshiva camp, and that he should play ball, go on occasional trips and make sure to respond kindly and articulately to people who speak to him, even if the subject is not Torah. Thus, on the matters of absolute halachah, Rav Moshe was unyielding and tough. However, when it came to perceptions of extremes and zealotry, Rav Moshe counseled normalcy and following a middle-of-the-road approach (page 387).

Finally, let us note that, like all gedolim, Rav Moshe did not always reveal his reasons and sources for a particular decision. It is our role as believers in emunas chachomim to listen and follow even when we do not understand. Sometimes, thirty years later, we are granted a glimpse of greatness. Rav Moshe once recommended that a certain ill man be given the added name Moshe. When the rosh yeshiva was asked by the patient’s father why he did not suggest the more traditional add-ons of Refoel or Chaim, Rav Moshe responded that since he had been told that these names were already in use in the family, he thought of Moshe. His logic was incredibly simple, yet brilliant. First of all, Moshe’s prayers were answered positively when he prayed for a cure for Miriam. Furthermore, since Moshe’s name means that “he was rescued from the water,” the name could also help someone to be saved from his own calamity. Later, Rav Moshe revealed to his family that since the Torah mentions at the end of Chumash that Moshe had never become ill, this was a good omen for someone ill as well (page 407).

May Rav Moshe’s holy neshamah continue to help all of us as we learn from his caring for every individual in Klal Yisroel and for the preservation of the pristine nature of the Torah forever.