The Disengagement was carried out on Tisha B’Av, 5765. It was a move presented by then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon as guaranteeing that we would achieve the height of peace, a diplomatic move meant to bring quiet to the region. And it was specifically Sharon, the hawkish right-wing leader whose stubborn visit to Har Habayis had ignited the flames of the Intifada in its time, who became the darling of the Arabs, even if his public addresses presented a different view.

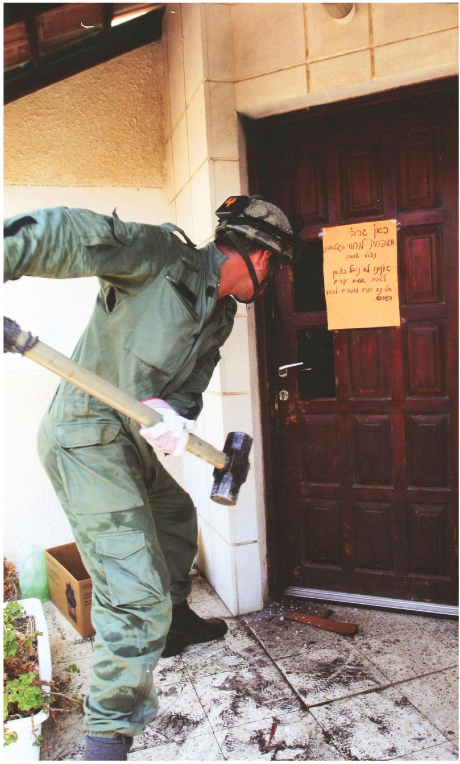

Nine years ago, on Tisha B’Av, following a bitter struggle that pitted Jew against Jew in the media, in city squares, and in the Knesset plenum, the die was cast. All of the entrances to the Gaza strip were sealed to visitors. That morning, on August 15, 2005, IDF soldiers and police officers delivered orders of evacuation to the residents of the settlements in Gush Katif. The soldiers were instructed to offer every possible form of assistance to any family interested in leaving on its own volition, and to show sensitivity to their pain. In some of the settlements, the soldiers did not even distribute the orders, due to the opposition of the residents.

The scenes of the Disengagement were horrifying. The sight of children forcibly wrested from their mothers’ arms was reminiscent of some of the darkest days of our history. It was heart wrenching to see shuls being emptied, and the collective cries pierced the heavens. The 102nd perek of Tehillim, “Tefillah l’oni ki yaatof,” was chanted over and over. The clashes between soldiers and local residents, most of whom were also members of the army, some of them even officers, left deep scars in the flesh of Israeli society, who wondered whether the Disengagement would indeed lead to peace.

The rocket fire that has taken place since that time and especially in recent days has left little doubt as to the answer to that question.

Then came the appeals to the Supreme Court to block the demolition of the shuls of Gush Katif. It was a struggle led by a group of rabbonim headed by Rav Simcha Hakohen Kook. The Supreme Court ultimately advised the government not to demolish the shuls, hoping that they would remain intact and would be placed under international protection. But the end of that story is one that we all know: The Palestinian rabble pounced on the shuls with shrieks of victory, looting their contents, wrecking the structures, and burning them down. The bitter taste of those flames has remained etched into our memories to this very day. Even before that, many tears were shed as the deceased Jews buried in Gush Katif were exhumed from their graves and reinterred in kevorim in Yerushalayim. The chief rabbi of the IDF at the time, Yisroel Weiss, was fiercely lambasted for the move; to this day, he has yet to shake off the trauma of that time. As a result of his ruling, he lost most of his friends and was discredited by the most respected rabbonim of the Zionist community.

Rav Avrohom Shapira, rosh yeshiva of Mercaz Harav and former chief rabbi of Israel, wrote at the time to Rabbi Weiss, who was his own talmid and had never made a move without his approval, “I was astonished by this, which in my humble opinion does not fit with the desire of the Torah. But that is not why I have troubled myself to send you this letter. Rather, it is because of the cynical exploitation of my name and its insinuation into your orders and instructions to the soldiers. Your claim that ‘Rav Shapira hasn’t told me to resign my commission, and he knows my views,’ and so forth is inappropriate. When we met, I made it clear to you in response to your question that in my opinion, it is absolutely forbidden to be a party or assist in any way in the expulsion of Jews from their homes, the destruction of shuls, and the damaging of kevorim, and that even a military rov of any rank is enjoined not to do these things, which are forbidden by the halachah.”

It is clear that Rabbi Weiss had managed to evoke the ire of Rav Avrohom Shapira, who continued in even harsher terms, “Using my name as if I agree with your actions on this matter is not correct. You were told explicitly at that meeting and afterward that in my opinion even a military rov may not violate the Torah. And giving a hechsher to the expulsion of Jews from their homes is a chillul Hashem!”

On August 22, the residents of Netzarim, the last remaining settlement in the Gaza strip, were evacuated. On August 23, the settlements of Chomesh and Sa-Nur in northern Samaria were dismantled. Dan Chalutz, the chief of staff of the IDF at the time, and Moshe Karadi, the police commissioner, praised the settlers and the rabbonim of the Yesha communities for working to cool down the flaring tempers and to prevent violence from erupting while the communities were evacuated. But the praise was unwarranted; the right wing had actually done everything in its power to prevent the evacuations, but it had been unsuccessful. The state (the government, the army, and the police) worked tenaciously and used all the force available to them. Or, in Sharon’s words, they worked “with determination and with sensitivity.” The determination, at any rate, was certainly present!

The Disengagement plan had been formulated by Ariel Sharon in April, 2004, three years after he was elected to the office of Prime Minister. It was initially presented in an interview with Haaretz. From Sharon’s perspective, that interview was a trial balloon, an attempt to gauge how the public would react to the idea. At the same time, he met with President Bush and managed to extract from him a written commitment to American support of Israel’s demands in any future negotiations with the Palestinians. Among the most significant terms were that the Palestinian “Right of Return” would be dropped and that the settlement blocs would not be dismantled. Both the Palestinians and the opponents of the Disengagement were dismayed by the letter. The latter group argued that the document contained no concrete promises; it consisted solely of ambiguous statements. The letter was ratified by both houses of Congress.

Sharon was certain, and he promised the public, that the Disengagement would lead to a peace agreement. One thing, he declared, was certain: There would be peace in the region. The threat of rocket fire and Kassam missiles would no longer hover over southern Israel. The people would no longer have to run to bomb shelters. Today, we can see quite clearly just how inaccurate and unrealistic Sharon’s predictions were.

It took the prime minister almost a year to carry out his plan. The plan met with fierce opposition within Israel. After intensive consultations and internal conflicts within the Likud, Sharon presented the government with a plan of far more limited scope than he had initially envisioned, one that called for Israel to pull out of the Gaza strip without evacuating its settlements. Some chose to ignore the inherent contradiction in the plan, while others maintained that it was merely paying lip service to the right. In order to ensure that his proposal would be approved by a majority in the government, the prime minister fired two right-wing ministers, in a step that was plagued by controversy and earned him harsh condemnations from the justices of Israel’s Supreme Court. Binyamin Netanyahu was among the supporters of Sharon’s plan in the government vote, although he later became one of its fiercest opponents.

On October 26, 2004, an updated Disengagement plan was approved in a Knesset vote by a majority of 67, with 45 votes against and seven abstaining. The Likud was split in its vote, and the vast majority of the left favored the plan. Most of the Arab parties abstained; Shas was opposed. Yahadut HaTorah was pressured to leave the coalition, but on the instructions of Rav Elyashiv, its members remained in the plenum and abstained from the vote.

The Disengagement was initially scheduled for August 14, 2005, which coincided with the ninth of Av. At the request of Israel’s chief rabbi at the time, Rav Yonah Metzger, it was postponed until the following day. The army finished its evacuation of the Gaza Strip on September 11, 2005. The next day, the strip and its abandoned settlements were the scene of massive Palestinian celebrations, including the destruction and burning of the shuls that had been left behind. In northern Shomron, the process concluded with the evacuation of the Dotan camp on September 22.

After the evacuations were carried out, a long process of resettling the evacuees began, a process that has not yet concluded. There was a severe dearth of resources to help the evacuees from the Disengagement. A state investigative committee that was subsequently established determined that the government had been guilty of a grave failure to properly take care of the needs of the evacuees, and that the Disengagement had resulted in severe violations of their human rights.

Moreover, according to the government’s decision on August 18, 2005, the government itself was responsible for building shuls to replace the ones that had been destroyed. The government had also promised to preserve portions of the shuls and to integrate them into the new ones that were to be built. But nothing seemed to come of that. The government simply did not live up to its commitments.

The following is a quote of the government’s decision in this regard: “The Ministry of Defense, at the earliest opportunity, will determine whether it is possible to dismantle the shuls in the evacuated area in such a way that they can be rebuilt elsewhere. In any event, as much as possible, symbolic portions of the shul structures will be taken and stored along with the shuls’ contents. It will be determined whether it is possible to integrate these components into the new shuls that will serve the settlers in their new locations.” Today, nine years later, a person reading these words does not know whether to laugh or cry. But one thing is clear: The Sharon government grossly misled the State of Israel.

And can any of us confidently rely on our current government?

At the beginning of this week, the Knesset hosted 500 children from the south for a day of activities at the Knesset. Yuli Edelstein, the Knesset Speaker, directed the Knesset director-general, Ronen Plot, to set up activities in the Knesset for children from the southern communities under fire, and the complicated operation got underway in the span of a few days. The deputy Minister of Education, MK Avi Wortzman, was also involved in helping to bring the children to the Knesset. The children arrived from many communities in the south: Sedot Negev, Ofakim, Kiryat Malachi, Even Shmuel, Moshav Eitan, and Kibbutz Saad. They were greeted by Knesset guides for a day filled with special, enjoyable activities, including a magic show, a tour of the Knesset, and other programs.

Yuli Edelstein cleared some time in his daily schedule to meet with the children and speak to them. “The lively atmosphere here speaks for itself,” he said. “The children are happy and smiling, enjoying this time of calm.”

Most incredibly, many of the children were members of families who were evacuated from Gush Katif nine years ago and have since been scattered throughout the settlements and kibbutzim in the south. Avi Wortzman, the deputy Minister of Education, who was one of the leaders of the initiative, told them, “You are my neighbors. I live in Beer Sheva, and I, along with my children, have sat in a bomb shelter, and it was not a pleasant experience. It has now been nine years since the Disengagement, since we were promised that the Disengagement would lead to quiet. Since then, thousands of missiles have been fired at Israel. I hope that the army will win the battle so that the children in the south and all the children throughout the country will never need to suffer again.” The Knesset is prepared to hold at least three similar days of programming for children from the south this week and next week.

The Knesset also held a special session this Tuesday to mark the ninth anniversary of the Disengagement. Dozens of speakers were scheduled to take part in the discussion. The issue is perhaps more pertinent than ever this year; it is impossible not to be reminded of the government’s empty promises nine years ago, when we are now seeing just how blind Sharon and the rest of the government were at the time.