Fear in the North and in the South

This past week was a time of fear both in the north and in the south. The winds of war were blowing and missiles were falling, but bechasdei Shomayim those intended for the north fell in the Kinneret. In addition, a Syrian plane was shot down after flying over Israel. Syria reacted by threatening war, and the residents of the north took refuge in their bomb shelters. Nevertheless, thousands could still be found in that region of the country during bein hazmanim.

I derived a bit of a mussar haskel from recent events. Two Syrian missiles were fired toward Israel, and the David’s Sling system was operated for the first time. And then … nothing happened. The system did not work.

David’s Sling is an upgraded version of the Magic Wand system, the most innovative defensive system that the State of Israel possesses. The system was developed by a collaborative effort of the military industries of Israel and America. It is supposed to be an enhanced version of the Iron Dome system, but it failed as it was put to the test.

The technical details of the David’s Sling system are long, complex and exhausting, but the basic idea is clear: It is considered the pinnacle of modern technology, integrating all of the newest and most sophisticated technological advancements. It is the work of the most capable minds in the air force and the scintillating instincts of the intelligence services. Why, then, did it fail? Because nothing can succeed without siyata diShmaya.

Tidbits

When I have time, I enjoy spending hot days on the beach. Part of the reason is that it gives me an opportunity to meet new people and I enjoy speaking to everyone I meet. The other day, on the beach in Bat Yam, I met a group of bochurim from Yeshivas Brisk. One of them, whose name is Edelstein, hails from Flatbush, and I watched as he delivered a chaburah at the beach. I must say that I am always impressed by yeshiva bochurim. Even when they are relaxing at the seashore, they are immersed in Torah study.

In other news, Yossi Deutsch has officially entered the mayoral race in Yerushalayim. Today, Deutsch is a deputy mayor under Nir Barkat, who is leaving office to pursue a career on the national front as a member of the Likud party. Barkat is doing the opposite of what Ehud Olmert once did; the latter left a position as a minister in the government to become involved in local politics.

In any event, the situation is beginning to grow tense. Will Deutsch succeed in defeating the other seven candidates and winning the office of mayor? This is probably a topic that would be worthy of a separate article.

Encounters with Greatness in America

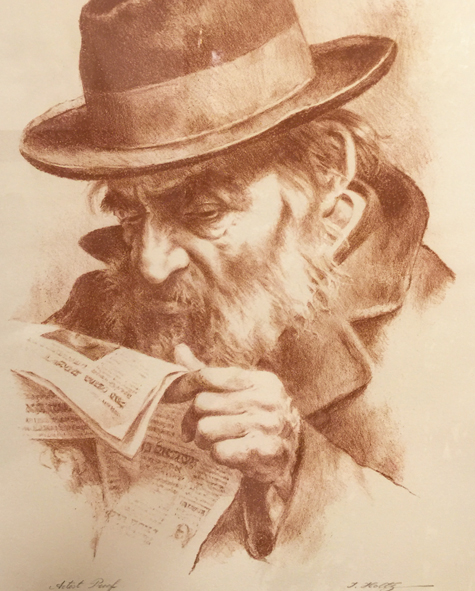

This week, I was asked to participate in a special project in which every writer was asked to select a photograph that was taken on his first trip out of the country and to write about the picture. I would like to share with you what I wrote.

My first trip out of Eretz Yisroel took me to America. I felt that the yeshiva where I was learning was too small for me, and it turned out that the feeling was mutual. The mechanchim who were responsible for me felt that it would be best for the yeshiva and for me if I spent a year abroad, so I traveled to Lakewood.

I spent three months in the Lakewood Yeshiva, under the auspices of my brother, who was a member of the kollel, and under the guidance of the mashgiach, Rav Nosson Wachtfogel. The latter advised me to transfer to Yeshiva Gedolah Zichron Moshe in South Fallsburg. I packed my belongings, bidding farewell to my Israeli friends who shared a basement apartment with me and took up the wanderer’s staff. In South Fallsburg, I spent an unforgettable nine months as a talmid of the rosh yeshiva, Rav Elya Ber Wachtfogel. At the end of the year, I flew home to Be’er Yaakov like a soldier returning from the front.

It was a year that left plenty of memorable impressions on me. A large number of gedolei Yisroel came to South Fallsburg during the summer, and we, the talmidim in the yeshiva, had the privilege of observing them and even receiving their brachos. To this day, I still possess a batch of letters that I received from Rav Shlomo Wolbe and Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro while I was in America, along with a volume of brilliant divrei Torah that I wrote up after hearing them from Rav Elya Ber, primarily at seudah shlishis at the yeshiva. Of course, I also have a large collection of pictures; even in those days, I was already a budding photographer.

On Pesach of that year, I had my first encounter with the second Seder night. On Purim night, I stood on the bleachers at to watch Rav Yitzchok Hutner.

Since that time, I have paid plenty of visits to America. I have seen the sights that the country has to offer, including the city of Manhattan, but none of those things moved me. I was once a participant in an academic tour of the United States from coast to coast, which included a trip to Washington, D.C., and its various institutions.

But it was my visit to America along with the Minister of the Interior of the State of Israel, Aryeh Deri, in mid-5749 (1989), that left the most powerful imprint on me. I was moved not by the respect that he was shown in the United States, but by our encounters with the gedolim of America. Deri was a guest at the Lakewood Yeshiva, as well as the institutions of Yeshivat Ateret Torah and the rabbonim of the Sephardic communities. He also met with executives of Merrill Lynch and with Mayor Ed Koch of New York City, and he visited the offices of Agudas Yisroel in Manhattan as a guest of Rabbi Moshe Sherer. A lengthy, low-profile meeting with Reb Moshe Reichman seemed to have been the factor that led to a matching grant program that would benefit the Torah world in Eretz Yisroel. Deri was also a guest of honor at the annual dinner of the Mir Yeshiva.

Perhaps the greatest highlight of that trip was a meeting with Rav Avrohom Pam, rosh yeshiva of Yeshivas Torah Vodaas. There were a few of us: Deri was accompanied by three of his close friends – Moshe Reich and ybl”c Itche Wolf and Shmuel Weinberg. There was also an imposing-looking bodyguard, and I was the final member of the group.

“This is it. This is his house,” Moshe Reich announced when we arrived. It was a simple-looking structure. Deri asked me to go to the door and to find out if we could enter the home. We were all excited by the upcoming encounter with a great tzaddik.

I knocked politely, and a pleasant-looking man answered the door. In light of his short jacket and ordinary-looking hat, I assumed that he was Rav Pam’s gabbai or perhaps a close talmid. Through the doorway, I could see that he had just finished setting a table. “Is the rosh yeshiva here?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied, answering me in Hebrew.

“Aryeh Deri is outside and wants to know if he can come in,” I said.

“Of course,” he said. “We are waiting for them.”

“Perhaps you could ask Rav Pam himself?” I said apologetically.

“That is me,” he replied.

The Researchers’ Mistake

The Knesset is now in its summer recess.

I recently came across a report on a study conducted by Dr. Assaf Shapira and two of his colleagues in his research institute, Shachaf Zamir and Avital Friedman, concerning the parties in the Knesset. These reports tend to make me tense. If there is any area with which I am familiar, it is the Knesset, its work, and the various political parties, and I sometimes come across erroneous conclusions drawn in this regard. This was indeed one such case. The researchers felt that United Torah Judaism is one of the most hardworking parties in the Knesset. However, they ranked the Shas party in the fourth or fifth place in that respect. I agree with their assessment of UTJ; the members of the party are widely admired for their diligence and dedication. But I could not accept the fact that the Shas party received a particularly low ranking. I disagreed with the critical tone of the institute’s assessment of the party’s work. With my familiarity with their parliamentary work, I felt compelled to inform Shapira and his colleagues that they had made a mistake. I even invited them to debate with me and to prove that they were correct.

One of the yardsticks utilized by the report to measure the parties’ industriousness areparliamentary queries. The researchers determined that UTJ is ranked in the third place in that respect, while the other parties in the coalition – Kulanu, Shas, Bayit Yehudi, and Likud – tend to use this parliamentary tool sparingly. I know that Shas is one of the parties that make the most prodigious use of parliamentary queries.

I proceeded to check the records in the Knesset database, where I was able to access a list of all 120 members of the Knesset and to review the number of parliamentary queries submitted by each one. According to the records, the members of the Shas party had submitted 97 queries – far more than any of the other parties.

I asked the researchers to identify the sources of their information, at least regarding the parliamentary queries. They confessed that they did not have access to the Knesset database. They asked to meet with me and to hear my objections to their findings; perhaps we will meet soon. The most important conclusion I drew was that even a prominent institute staffed by highly respected researchers can make mistakes – which is not to say that anyone should have thought otherwise.

Thinking Big in the Matnas

I recently saw an advertisement published by the local Matnas (neighborhood community center) in the Shmuel Hanovi neighborhood of Yerushalayim. Upon reading the details of the Matnas’s summer programming, I found myself riddled by conflicting emotions: I was impressed by the ambition of the programming, and I was pained by the fact that our own Matnas in Givat Shaul does not offer anything on the same scale. If the administration of a Matnas thinks big, they can offer an impressive array of activities. If they settle for minimal accomplishments, on the other hand, they will remain largely ineffective.

During the course of the bein hazmanim, the Matnas promised an impressive array of activities: hiking trips and organized visits to kivrei tzaddikim, a panel discussion on chinuch with Rav Aharon Friedman, a kumzitz with Shloime Gertner and the Menagnim orchestra, a workshop for chassanim, a shmuess from Rav Rachamim Ziat, a chizuk gathering with the participation of several gedolim, home economics lessons for chassanim, a nighttime bike trip, nighttime swimming, inflatable castles for children, a chiddushei Torah project, and an evening of preparation for the month of Elul with Rav Shmuel Greineman.

And that is not all. Additional programs include a shiur by Rav Mordechai Neugroschel on the subjects of golus and geulah (to take place in the auditorium of the Bais Yaakov school in Sanhedria Murchevet, with an admission fee of 15 shekels), a screening of the film “Pitom,” swimming lessons, and a puppet show. The Matnas is also partnering with another organization to offer a course for people who are interested in opening their own businesses.

It is quite impressive, and the lesson is clear: If the people who are hired to serve the community approach their work with a sense of mission, with a desire to help the public, and with a broad perspective, then they will be able to pride themselves on their impressive achievements.

If only my own local Matnas would follow their example….

Chareidi Satisfaction

A recent headline in Maariv stated, “Life Is Good in Israel – Especially If You Are Jewish.” If the headline had continued, it would have added, “and even more so if you are chareidi.” The article is based on the findings of the Central Bureau of Statistics based on a survey conducted in the year 2016. I do not consider all of their findings reliable, but they reported that at the end of the year 2016, 75 percent of the population of Israel was Jewish. (It is important, however, to note that the figures are slightly skewed, since 35 percent of the people of Israel are immigrants, and 65 percent of the immigrants are actually not Jewish, even if the bureau considers them Jews.)

Interestingly, the majority of Jews of Israel are not chilonim. The bureau found that 25 percent of the Jews in Israel define themselves as traditional, about 16 percent define themselves as “very religious,” and about 14 percent consider themselves chareidim. If we discount the non-Jews whom the institute considered Jewish – who probably fall into the category of chilonim in their report – then the percentage of religious Jews would increase significantly.

The report also stated that 89.9 percent of the Jews in Israel are satisfied with their lives in the country, as opposed to the Arabs, whose rate of satisfaction is 80.7 percent. “Among the Jews,” the article stated, “the chareidim have the greatest satisfaction from their lives and their financial situations in contrast to the remainder of the populace of Israel.”

The report states that chilonim smoke more than chareidim. On the other hand, some may find it quite surprising that the level of satisfaction with life among chareidim was so high, while the rate of employment among chareidi men is significantly lower than among the chilonim. In the chareidi community, 41.6 percent of the men are employed, whereas the rate in the chiloni community stands at 75 percent. One of the writers in The Marker could not hide his envy when he reported on the study’s findings. “There is a group within our populace,” he wrote, “that has managed to crack the secret [of happiness] with great success. They achieve it with a very interesting approach: They work very little, they earn less than they spend, they give more to others than any other group in Israeli society, they are not involved in sports, they have large families, and at the bottom line, they are happier than any other group in Israeli society.” All that a person needs to do in order to be happy, he revealed to his readers, is to become chareidi and to move to Bnei Brak.

“Why are they so content?” he went on to ask, struggling to resolve the riddle to his satisfaction. “It makes a person wonder. The average Israeli will ask: How can it be that I earn more than the chareidi, I live in a more spacious apartment, I am more educated than he is, I travel abroad more often, I am more involved in sports (all this is based on the report), and yet he is more satisfied with life and even with his financial situation?”

It would be quite difficult to explain the underpinnings of the chareidi mentality to the writer of this article. There is the fact that this world is merely a vestibule leading to the World to Come, that a person who gives is a person who truly receives, and that we all have an obligation to give maaser and to help our family members and others in need. There are principles such as the concept that “the only free person is one who is involved in Torah,” the principle that “he who acquires more property acquires more worries,” or the Mishnah that teaches us, “Eat bread with salt … and it will be good for you in this world.” If a chiloni hears these things, he will only become more puzzled. He may arrive at the conclusion – which is correct – that there is actually no connection between wealth and happiness, but he will explain it in his own way. When everyone is poor and there is no inequality, he will think, then everyone is bound to be happy because there is nothing to envy, and there is some logic to that. He will also reason that the fact that chareidim help each other contributes to the general sense of happiness. That, too, is true, but it is not a complete explanation.

I also liked another of the writer’s statements: “Another explanation is the claim that chareidim are content with very little and are happy with their lots, whereas the rest of the populace will never be satisfied with what they acquire.”

Madness About Mingling

At a convention center in Tel Aviv, an event was organized for religious people. There were two elevators in the building, and one was marked “men” while the other was marked “women.” Haaretz soon found out about this, and the result was a massive uproar. The newspaper related with horror that Naftali Bennett and Uri Ariel had participated in the event. The Tel Aviv municipality, which is the owner of the convention center, was “rebuked.” But Rav Yehoshua Shapira, rosh yeshiva of a hesder yeshiva, was not fazed. “This was respectful to both men and women,” he insisted. “Tznius is an institution that causes the Shechinah to rest upon the Jews.”

There is a public swimming pool in Kiryat Arba, and a handful of chilonim demanded hours for mixed swimming. The rabbonim of the community ruled that it was prohibited, and the small group of chilonim, aided by a yarmulka-wearing attorney, petitioned the Supreme Court. Needless to say, the court ruled in their favor. The rabbonim responded by ordering the community not to use the swimming pool even during the separate hours. For lack of a sufficient customer base with an interest in mixed swimming, the pool quickly ran up a deficit, and it is now in danger of closing.

The Witness Who Recanted

Sometimes, reading the response to a parliamentary question is enough to make a person’s blood boil. This was a question posed by a member of the Kensset to the Minister of Justice, Ayelet Shaked: “Moshe Sela, the state witness in the trial of Rabbi Shlomo Benizri, has confessed that he testified falsely and made incriminating statements about Benizri due to the incentives offered to him at the time and the pressure that was placed on him. Doesn’t this extraordinary development necessitate a new review of the case?”

It was a simple question, and the answer should have been clear. But the minister’s response was disappointing, to say the least. She explained that she was not involved in the judicial process, and she cited the response of the prosecution. “The agreement with state witness Moshe Sela,” they claimed, “was signed only after the police and the prosecution concluded that the testimony that he planned to deliver was true and was supported by copious external evidence.” Shaked claimed that other witnesses had testified that Sela had told them, long before the criminal investigation was opened, about crimes he committed together with Benizri, and that the court had accepted the prosecution’s position. In conclusion, she said, “In light of the above, the prosecution has not found that the comments of the state witness to the media justify reopening the case. It has determined that there is no reason to suspect that his current statements are truthful, rather than the statements that he made as a witness at the trial, which were supported by ample external evidence.”

What do I find disappointing about this? Despite all of the prosecution’s arguments, the simple fact remains that Moshe Sela has now come forward and claimed that he lied. What difference does it make that he told the police or others at the time that he and Rabbi Shlomo Benizri had committed crimes together? That was the story that he was maintaining at the time, for whatever reason he felt compelled to do so, primarily the fear that his life would be destroyed if he did not cooperate with the prosecutors. Now that he is claiming that he lied, it means that he lied in every context at the time – in his interrogation, in court, and even in private conversations. If someone repeats a lie several times, should that give it any more credibility? If Sela is now admitting that he lied, shouldn’t the prosecution take a step back and examine whether the outcome of the case was justified?

Truckloads of Immigrants

Michoel Malchieli was one of the Knesset MKs who spoke at a recent “day of appreciation” for development towns. The address he delivered was not recited from a written script. He spoke off the cuff – and from the heart.

“I believe,” he said, “that we are steadily increasing our understanding of the importance of the contributions made by the development towns to the State of Israel as a whole. At the beginning, the immigrants in these communities were viewed as second-class citizens. They were not respected for the values that they brought with them… My grandfather of blessed memory told me that when he came to Eretz Yisroel, his family was taken together with a group of immigrants to the distant north. They were placed on a truck – without any seats; there was nowhere for them to sit. They were all crammed into the truck, and they drove for hours, without air conditioning. They are all together – with children, with babies, and with all their belongings. When they arrived, the driver did not even hesitate. He flipped a switch, and all of the people were dumped on the ground like so much sand. The people didn’t understand why he had done that. They thought he had gone berserk. But over the years, as they met their relatives and other immigrants, especially those from eastern countries, they heard similar stories.

“Do you know where those people were sent? They were sent to the development towns. The attitudes toward them were so contemptuous that my grandfather told me that he once went to vote, and the worker at the polling station handed him a ballot and an envelope. He chose his vote for him. Why did he tell me this? Because when I was a child, I went to my grandfather and told him that Rav Ovadiah asked everyone to vote, and he said, ‘No. I don’t vote for anyone. Everyone there is a liar.’

“‘Why?’ I asked.

“He said to me, ‘Are they also going to tell you what to do?’

“‘What do you mean ‘tell me what to do?’ I asked. ‘You go behind the curtain, you take whichever slip of paper you choose, and you put it in the box.’

“Then he said to me, ‘No. When I first came to this country, the workers at the polling stations used to hand us the slips together with the envelopes.’ They would tell him which ballots to use. He was naïve, and he thought that that was how a person voted. That was how they were regarded.”

“More than that,” Malchieli continued, “these were people who had come from the countries of the east with a rich culture of Torah, ethics, even music. They certainly had moral values. The operatives of the Ministry of Education came to them and told them that they had to send their children to a specific school. My grandfather said, ‘Wait a minute. They don’t dress modestly there, there is no Torah, and they do not learn how to read pesukim.’ And the people from the ministry said, ‘That is the way it is in Eretz Yisroel. This is what the rabbonim said to do.’ He was naïve and not very aggressive, so he said, ‘All right, let them go there. If that is the way it is in Eretz Yisroel, then that is the way it is.’ Many years passed, and the Torah sought out its dwelling place. The next generation has already come home. I think that today, we must truly appreciate those people who did everything that was asked of them, without complaint or resistance. I once told my grandfather that I had received a ticket for a parking infraction. ‘Look how cruel the inspector is,’ I said. He replied, ‘Take that ticket and hang it up in your house. You received a ticket from a Jewish policeman. Would you prefer to have received one from a Jordanian policeman?’ He saw no evil. He saw only good in the state. Until the very last day of their lives, the immigrants saw the establishment as a good thing, a praiseworthy thing. The time has come to speak highly of those people who never fought back against the evil that was done to them.”

Ahmed Tibi Argues with the Minister

Ahmed Tibi is a sharp-tongued Arab member of the Knesset who served in the past as an advisor to the terrorist Yassir Arafat. He is a doctor and an eloquent orator, and is not far from the extremist Arab MKs, Zoabi and Ghattas. He is an enemy of the Jews, in my opinion, who serves as a deputy chairman of the Knesset and is a member of the rotation of MKs who preside over Knesset sittings. It is never boring when he is involved in a debate.

Tibi recently called on Gilad Erdan, the Minister of Internal Security, to respond to a series of parliamentary questions, one of which Tibi himself had submitted. As usual, he proceeded to introduce himself from the chairman’s seat: “One interesting MK asked about the attacks by police officers on Arab protestors who were waving the Palestinian flag. The questioner is serving at this very moment as the chairman of the sitting.”

“Is that acceptable according to the regulations?” Erdan asked as he made his way to the podium.

“I make that decision, since I have authority over everything at this moment,” Tibi replied. He then began reading his question: “In a protest against the opening of the American embassy in Yerushalayim, the police—”

“I didn’t dispute your authority,” Erdan interrupted him. “I merely asked if you could refer me to the relevant clause.”

“After you answer the question,” Tibi replied. He concluded his question, asserting that the police had brutally beaten the Arab parliamentarians without showing restraint.

“Mr. Chairman, I will try to answer,” Erdan said.

“Be restrained,” Tibi interrupted him.

“I hope that you, as an intelligent person, will be successful in presiding over the sitting and absorbing the answer,” Erdan said.

As could be expected, Erdan conveyed the response of the police to the allegations. “The police have informed me that in contrast to what was claimed in the question, the Israel Police prepared for that event – which I view as a very joyous and exciting event – of the transfer of the American embassy to Yerushalayim. In the course of the preparations, the police also authorized the demonstrations that would run concurrently with the ceremony…. During the demonstration, some of the protestors began waving the flag of the Palestinian Authority….” Erdan and Tibi proceeded to debate whether it was actually the flag of the PA and whether the protestors’ actions constituted a criminal offense.

“An additional question,” Tibi said. “First of all, it was not the flag of the PLO, and second, it was not the flag of the PA. As you know, the PA was established only recently, about 20 years ago, and this flag existed long before that.” Erdan added that the incident turned violent, and since the subject had been relayed to the internal investigations department of the police force for further study, he would refrain from discussing it.

“A police officer’s job is very difficult, very frustrating, and very thankless,” Erdan said.

“And sometimes very violent,” Tibi added.

“I understand that you have no further questions,” Erdan said. “Do not lose your right to ask an additional question.”

“At this point,” Tibi replied, “I am returning to my job as the chairman of the sitting, and I thank you for responding.”

Erdan said, “In any event, I hope that you will have the opportunity to protest the transfers of many more embassies to Yerushalayim. We will try, with each successive protest, to make sure that the police conduct themselves appropriately.”

“He who laughs last laughs best,” Tibi shot back. “Thank you, Mr. Minister.”

“You are welcome,” said Erdan, making sure to get the last word.