Parshas Devorim, which we read this week, like the entire final seder of the Torah, represents Moshe Rabbeinu’s farewell message to his people. The parsha introduces us to the seder that describes the sojourn of the Bnei Yisroel in the midbar and ends with prophetic words concerning their entry into Eretz Yisroel.

The Jewish people went on to settle the land, erected the Mishkon in Shilo, built the Botei Mikdosh, experienced two churbanos, and were then tragically evicted from the land promised to them. They were sent into golus, where we remain until this day. We will reach our desired state of shleimus when we are gathered from exile and permanently brought to Eretz Yisroel with the geulah.

Rabbeinu Bechaya (Devorim 1:1, 30:3) explains that the main role of Eretz Yisroel will also only be realized after the final redemption. Our people lived in the land for a temporary, relatively short period. After Moshiach returns us to the Promised Land, the purpose for which the world was created will be realized. Thus, the final pesukim of the Torah connect to its beginning in Bereishis, for the permanent return to Eretz Yisroel is akin to the creation of the world, which will then begin realizing the purpose for which it was established.

Similarly, Chazal teach, “Sofo na’utz b’sechilaso,” the end is tied to and rooted in the beginning. The paths, peaks and valleys of our existence combine to lead to our destiny.

Seder Devorim begins with Moshe Rabbeinu rebuking his people, for in order to merit geulah and entry into Eretz Yisroel, they had to engage in teshuvah. As the Rambam says (Hilchos Teshuva 7:5), “Ein Yisroel nigolin elah beseshuvah,” Klal Yisroel will only be redeemed if we engage in proper and complete teshuvah.

Since Moshe loved his nation and selflessly wanted them to be able to enter the land that Hashem promised to their forefathers, he admonished them with love and respect so that they would accept his tochachah. He spoke to them in a way that preserved their self-esteem (Rashi, Devorim 1:1; see also Rambam Hilchos Teshuva 4:2), because he knew that for people to accept mussar, it is usually advantageous to maintain their dignity.

It’s not as if Moshe wasn’t aware of their obstinate and disrespectful nature. Rashi (ibid.) explains that he spoke these words of mussar only after the entire nation had gathered in one place. Moshe knew the nature of these people and wanted to prevent loathsome characters from being able to proclaim that had they been there, they would have spoken back to and challenged Moshe. Therefore, he gathered them all together, indicating, “If you have what to say, say it here to my face.”

Despite his keen understanding of their displeasing behavior, his speech was laced with love and respect. The role of parents, teachers and leaders when reproaching is to do so without destroying the person, while providing clarity about the correct path, and conveying confidence for the future.

It is commonly noted that we read this parsha before Tisha B’Av because it contains Moshe’s admonition beginning with the word “Eicha,” which we lain in the same tune as Megillas Eicha on Tisha B’Av.

Perhaps we can suggest that another reason is to teach us how to give mussar and bring people home. It is not by demeaning them, yelling at them, or making them feel utterly useless. It is by carefully crafting the corrective message and infusing it with love, demonstrating that it emanates from a loving and intelligent heart.

Man is created with a heart and a brain, impulses and emotions, competing character traits, and a complicated psychology and thinking process. In his youth, he requires parents and teachers to set him on the proper path, and teach him Torah, responsibility and manners. He needs to be shown and taught how to think and how to act. Man has successes and failures as he goes through life. Due to his very nature, he often requires course corrections by those who care about him.

Torah and mitzvos help him battle the ever-present yeitzer hora, but that is not always sufficient. Every generation has unique temptations. The further we get from Sinai, the harder it is to deal with them. Just like Noach in his day – Chazal say, “Noach hayah tzorich sa’ad letomcho” – we all need help to make it and can’t do it on our own.

To the degree that others recognize this, they can be sources of support and constructive chastisement.

It is interesting that this month of Jewish tragedy is referred to as Chodesh Av, which is the same as the word meaning father. Perhaps we can say that it is a reminder to us to reprimand those whose sins prevent us from realizing the redemption, with fatherly love; treating others as a father would and lending them a shoulder to lean on to contemplate their situation, and a hand to help them climb and rise.

It is a reminder to act as Moshe did, admonishing in a way that could be accepted so that the people would merit exiting their golus and entering the land of geulah.

Another understanding of the name can be gleaned from a story about the Divrei Chaim of Sanz, who lost a child and was distraught. The rebbe was overcome at the Friday funeral, but although he was clearly devastated, when Shabbos began, his face glowed with its usual radiance and joy.

Chassidim asked the rebbe how he was able to find the strength to rise above the pain. He offered a parable of a person walking along a street and suddenly felt a pat on his back. Startled, he turned around, only to see that what he felt was actually a loving pat from his father.

“I felt the blow,” said the rebbe, “but then I saw who it was from: my beloved Father.”

The Torah teaches us to understand difficult moments by recognizing that “just as a father punishes his son, Hashem punishes Klal Yisroel” (Devorim 8:5).

We are to understand that when we are hurt, it is an act of love, not anger. A parent disciplines because he wants to prod his child to growth and success. Even when the admonishment is painful, it is understood to be in context of parental love and hope.

So, during Chodesh Av, we read this week’s parsha, in which Moshe Rabbeinu, the av lenevi’im, the most effective rebbi we have ever had and the eternal Jewish father figure, demonstrates how a loving father offers rebuke.

In order to bring people to teshuvah, which will bring us to the ultimate geulah, we need to preach as Moshe preached, and rebuke and reprimand as he did.

An examination of the posuk beginning with the word “Eicha,” reveals the state of the Jewish people at the time of Moshe Rabbeinu’s talk with them. Far from a great people simply lacking in refinement, they were actually rambunctious apikorsim, who would mock Moshe and incessantly quarrel among themselves (Rashi, Devorim 1:12).

Yet, Moshe saw greatness in them and worked to bring them to the level that would allow Hashem to end their golus and bring them to Eretz Yisroel. So too, in our day, if we are mochiach with love, treating all Jews as brothers and sisters, and care about them, we can also help bring the nation out of golus and into geulah.

Rav Simcha Bunim Cohen was a young bochur when he first met Rav Moshe Feinstein. A resident of the Lower East Side, he entered the MTJ bais medrash for the first time to daven Minchah and approached Rav Moshe. The rosh yeshiva was engrossed in a sugya, so the bochur waited patiently for him to raise his head from the seforim in front of him.

Finally, Rav Moshe noticed the young boy standing there and extended his hand to him. He said, “Shalom Aleichem,” and asked him his name. After some small talk, Rav Moshe rose from his seat and led the bochur by hand to the back of the bais medrash. “Come,” he said, “let me show you where the siddurim are. It’s your first time here, so you probably don’t know.”

After showing him where the siddurim were kept, the elderly gaon began taking the boy down a set of stairs.

“Where are we going?” Simcha Bunim asked.

“I want to show you where the bais hakisei is,” said Rav Moshe.

The bochur was overcome by the effusive love that the gaon hador showed him, a lesson he shall never forget.

The love of a leader, a rebbi, a rosh yeshiva, for a young bochur he didn’t even know, like a father for his child.

The boy went home to write in his diary how impressed he was and that he would make it his business to return to see Rav Moshe again. Within a few days, he was back. He went on to establish a special relationship with Rav Moshe.

Several years later, he was learning at the Mir Yeshiva in Eretz Yisroel and felt that it was time to return home. His rebbi, Rav Nochum Partzovitz, suggested that he would benefit from remaining in the yeshiva for one more zeman. When Simcha Bunim demurred, Rav Nochum proposed that he address the question to Rav Moshe Feinstein.

A few days later, Rav Moshe handed a tape with a recorded message to Rav Simcha Bunim’s father. Rav Moshe advised him to stay in the Mir for another zeman. “If Moshiach comes,” Rav Moshe said, “we will meet in Yerushalayim. If chas veshalom not, I guarantee you that I will be here when you return to New York.” Then he recorded on the cassette tape a 15-minute ma’amar of chizuk for the young bochur.

Simcha Bunim took the tape to Rav Nochum and they listened to it together. As they heard Rav Moshe speak, tears streamed down Rav Nochum’s face. He was overwhelmed and overcome as he listened; he couldn’t stop crying. When it was over, he explained how touched he was by the love of the elderly gadol hador for a young bochur thousands of miles away.

The love of Moshe, the love of a leader for his flock, the love of a rebbi for a talmid, ensuring that he would do the right thing and feel good about it.

A paradox appears in the words of Chazal: “Yehi beischa posuach l’revacha – May your home be open wide before the masses.” Yet, we’re also taught, “Yehi beischa beis va’ad lachachomim – May your home be a gathering place for talmidei chachomim.”

Which is the correct way to run a Jewish home?

Rav Meir Chodosh answered that the home should be open to all who need entry, but the mandate of the host is to ensure that all who enter depart his dwelling a little wiser than when they entered.

Rav Meir Chodosh answered that the home should be open to all who need entry, but the mandate of the host is to ensure that all who enter depart his dwelling a little wiser than when they entered.

Unconditional love and acceptance, with a mission to educate. And it is possible to do both.

Such was the legacy of the mussar giant, Rav Meir Chodosh. His home in the Chevroner Yeshiva, breeding ground for generations of talmidei chachomim, was marked by the carton of cookies that sat in the kitchen next to the steaming urn. The treats were set up for the bochurim of the yeshiva, who were encouraged to enter and partake of coffee, tea and cookies 24/7.

The ideals of the Chevroner mashgiach lived on and were embodied by his son, Rav Moshe Mordechai Chodosh, who passed away last week after a short illness.

Through example and message, his parents raised him to appreciate that the highest calling is helping others. As one of the yeshiva’s most respected and accomplished bochurim, he was the first to offer shalom aleichem to a newcomer. He was always ready with a smile and kind word to lift sagging spirits.

He exuded sweetness and warmth, personifying the human touch. He was relatable and pleasant. His shiurim were outstanding in their crystalline clarity and sparkling simplicity. The yeshivos he headed were not only for metzuyanim, nor for struggling teenagers, nor for those in between. They were for all of them. Bochurim. Bnei Torah. He welcomed them all and loved them all.

I came to know him when I was learning in Brisk and living in the Ezras Torah neighborhood, where his nascent yeshiva was located. Decades later, after his yeshiva greatly expanded and he established and led many others, as a renowned rosh yeshiva with legions of talmidim, he had the same ever-present, warm smile and welcoming countenance.

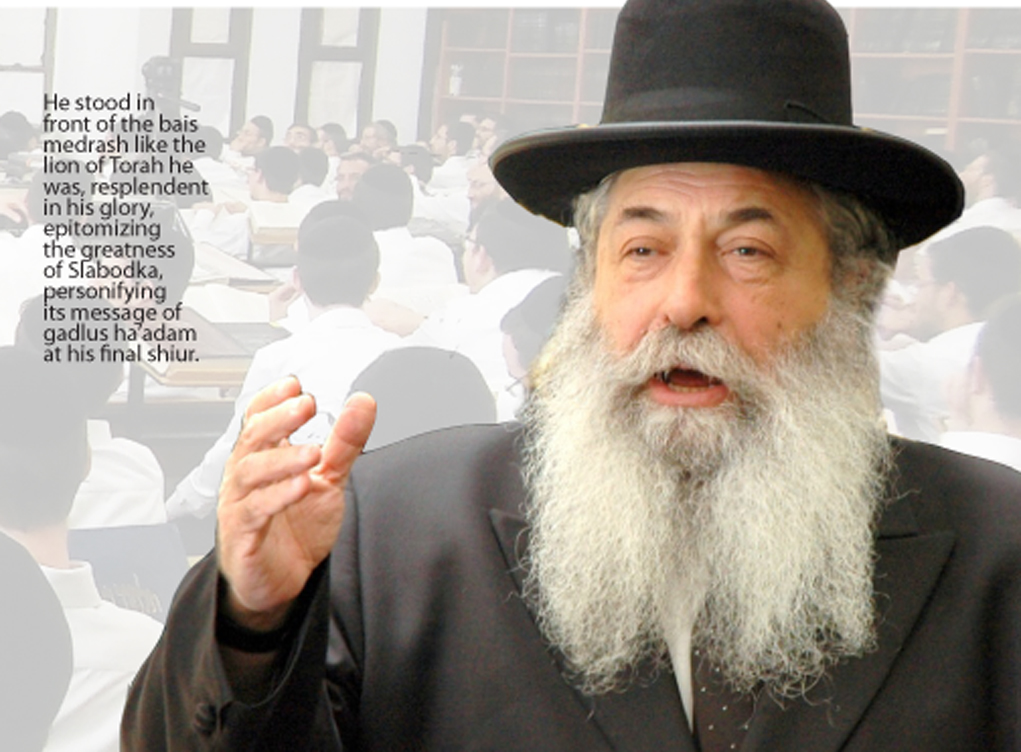

When he became ill and was told that he would be placed in isolation so that the advanced treatment would work, he first returned to his yeshiva to deliver a final, parting shiur. The sight was so amazing and awesome that we chronicled it in the Yated with a front page report. The image of that final shiur will live on for a long time.

He stood in front of the bais medrash like the lion of Torah he was, resplendent in his glory, epitomizing the greatness of Slabodka, personifying its message of gadlus ha’adam, displaying the love of a great soul at its apex, enveloped in Torah, surrounded by beloved students.

Seemingly oblivious to his physical condition, that image of the rosh yeshiva, smiling as he carefully dissected and laid out a sugya, transmitting the mesorah and beauty of Torah to the next generation, helping develop the minds and thinking of beloved talmidim for one last time, was similar to Moshe Rabbeinu’s parting from his flock on his last day.

The image of that soft smile, brilliant mind, faithful soul, and hadras ponim radiating yiras Shomayim and Torah will embolden his many talmidim and others as they face challenges and seek motivation throughout their lives.

When the shiur ended, the talmidim rose and lined up for a final encounter, to sear the image and message on their growing, maturing neshamos in a beautiful, heart-breaking, reflection of this week’s parsha. “Eileh hadevorim asher dibber Moshe.”

His passing was itself a shiur, and those who hear the song of history can’t help but appreciate that this also was his mesorah.

When Rav Simcha Wasserman sought to establish a yeshiva in memory of his sainted father, Rav Elchonon, he looked for the perfect rosh yeshiva to head the institution and teach talmidim. Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach suggested that Rav Moshe Mordechai Chodosh was the man for the job.

Rav Chodosh led the yeshiva to great heights, never forgetting whose yeshiva it was. He marked the yahrtzeit of Rav Elchonon and made Rav Elchonon’s Torah a centerpiece of his shiurim. Like Rav Elchonon, who viewed himself as a rebbi to young bochurim, Rav Moshe focused on his shiurim.

And now there is another feature of Rav Elchonon’s greatness that he emulated.

Rav Elchonon gave up his life al kiddush Hashem in spectacular fashion, urging his fellow kedoshim to “Prepare to die with pure thoughts, so that we may ascend to heaven as perfect korbanos. Let us walk with our heads held high. Let no one think a thought that would disqualify his offering. We are about to fulfill the greatest mitzvah, the mitzvah of kiddush Hashem.”

His tragic end was the modern-day equivalent of the death of the great Tanna, Rabi Akiva.

As Rabi Akiva prepared for his end at the hands of the evil Romans, his talmidim wondered, “Rabbeinu, ad kan? Is this what’s demanded of man, to approach such brutal sadism with a smile?”

The Piaseczna Rebbe explained that the talmidim weren’t asking a hashkafic question because their faith was tested. They weren’t pondering the secrets of the universe. What they were really asking Rabi Akiva was how they could tap into his faith. They were asking their rebbi to convey to them what inspired him so that they, as well, would feel it. They were asking for a parting shiur.

Rabi Akiva left this world before the eyes of eager talmidim delivering one final lesson. Rav Elchonon entered the pantheon of great men who gave their lives al kiddush Hashem delivering a shiur with his passing.

Rav Moshe Chodosh learned the lesson taught by the sainted Baranovitcher rosh yeshiva and delivered a shiur in kiddush Hashem before his passing.

Misas tzaddikim is as difficult as the churban of the Bais Hamikdosh. We cry for all of them, for rabbeim and their talmidim, for fathers and mothers and children, for rabbonim and their kehillos, for communities and their leaders, for the shopkeepers and scribes and beggars.

So much Jewish blood has been shed. So much heartache has been felt throughout the centuries in exile. On Tisha B’Av, we sit on the floor and plaintively ask, “Lamah lanetzach tishkacheinu?” For how long will death endure? For how much longer will we linger in golus?

When will You say that enough is enough, ad kan?

Help us follow in the paths of Moshe Rabbeinu and the Moshes of every generation. Help us love all Jews and bring them back. Help us show them the way so that we can all finally go home.

Hashiveinu Hashem eilecha venoshuvah, chadeish yomeinu k’kedem.