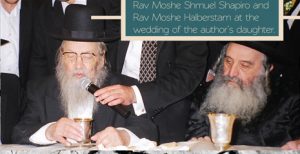

My family and I had two personal “rabbeim,” whose sagacious counsel we sought before making any significant move in life. They were both world-class Torah leaders, but they were also our guides in life, and they were available to us whenever we needed them. They were with us at times of hardship and times of joy alike, and they accompanied us through every significant event in our lives. And both of them passed away ten years ago this week. They were Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro zt”l and Rav Moshe Halberstam zt”l.

In this tribute, we present some brief thoughts in memory of the two great “Moshes” who had such a meaningful impact on our lives.

On the surface, there does not seem to be any connection between the two of them. They were both venerated leaders, men of great deeds and accomplishments who were among the giants of our nation. One was a rosh yeshiva for thousands of talmidim and was counted among the royalty of Brisk, a man whose chiddushim have been studied in depth by the greatest talmidei chachomim of our day. He lived for ten years in the quiet, obscure community of Be’er Yaakov, until he became known as one of the foremost gedolei Torah of Eretz Yisroel. His name was Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro.

The other, a well-known posek and member of the Badatz of the Eidah Hachareidis, was a renowned public figure who was a member – and, in many cases, the president – of every important organization in the country. He lived on Rechov Yoel, in the heart of the neighborhood of Geulah, and his name was Rav Moshe Halberstam.

Rav Moshe Halberstam’s approbation can be found in countless seforim, and thousands of people flocked to him for advice and guidance. He was a distinguished posek and one of the closest talmidim of Rav Shmuel Halevi Wosner zt”l. He also held many public positions. He was the president of Hatzolah and was the rov of the patients at Bikur Cholim and Shaarei Tzedek hospitals.

I remember the day of his petirah, the 28th of Nissan, 5766 (April 26, 2006), as if it were yesterday. When the news that he had collapsed was announced, people could not believe that it was true. The reports spread like wildfire: “Rav Moshe Halberstam had a heart attack in his home. The Hatzolah men are there; they are trying to stabilize his condition.” And then the situation reached its dreaded conclusion.

I was at the levayah until it ended, and I was one of the last people to leave his kever on Har Hazeisim that day. For the past ten years, I have made the trip to his burial site every year on his yahrtzeit. I also maintain ties with his family. My wife pays frequent visits to his rebbetzin, who lives with another family member in their home on Rechov Yoel.

He was both a rebbi and a father figure to us. Ten years ago, I was there to escort him on his final journey on this world, but before that, for over 20 years, Rav Moshe was our companion in life. His rulings determined every step we took. I refer to him unabashedly as our guide, for he was a spiritual guide to me and to my entire family. On the day of his passing, my home was plunged into mourning.

That year, we visited Rav Moshe before Pesach to receive his brachah, as we did at the beginning of every Yom Tov. On Chol Hamoed, we called him with a shailah. Three days before his passing, he listened as we shared a long list of halachic and personal dilemmas with him over the phone, and he gave us detailed instructions on how to deal with each of them. At the end of our conversation, he added a comment that, in retrospect, is quite chilling: “If you are unable to reach me,” he said, “then be in touch with Rav X.” He gave us the name and telephone number of another rov, adding in a reassuring tone, “I rely on him absolutely.”

“If you are unable to reach me…” Those were the words he uttered to my wife three days before his passing. Today, those words have taken on another dimension of meaning. It isn’t just that we are unable to reach him by phone; it is that we can never reach his lofty stature. Today, in hindsight, I am astounded at the fact that we were able to feel close to such a towering giant. In his kindness, Rav Moshe not only allowed us to consult with him at any time, unconditionally, but he also gave us the sense that it was entirely natural and reasonable for us to do so.

The last time I had the privilege of being in his presence, Rav Moshe was physically weak, but his spirit was as powerful as ever. In the middle of our conversation, he took a telephone call from a young rov of a hospital in Yerushalayim. I was only able to hear Rav Moshe’s side of the conversation, which dealt with the use of the hospital’s hot water faucets on Pesach. After he had given his p’sak, he added, “I know that they are going to yell at you, but don’t give in. This is the halachah and you are the rov, and you have to insist on it. Don’t worry. They will be angry, but they will ultimately accept your opinion.” With those words, aside from paskening for the young rov, Rav Moshe advised him on how to implement his p’sak and also – perhaps more importantly – infused him with courage and strength.

Rav Moshe was a source of sage counsel and halachic rulings for Jews of every stripe and in every imaginable situation. He rendered piskei halachah for large organizations, chesed institutions, and yeshivos alike. Very few people could claim to be as busy as he was, yet he somehow managed to be attentive to the needs of every individual and to find time for everyone who needed him.

Ten years after his passing, we still feel orphaned.

I have never succeeded in deciphering the secret of his strength. He was a unique individual, whose influence extended far beyond the Eidah Hachareidis. He was a member of the Badatz and his membership was sought by countless other organizations, as if it was considered a segulah for success. He lived in Meah Shearim, yet he was a father figure to thousands of people from every sector of society. His aura of power and confidence stemmed from his broad knowledge and firm commitment to truth. He was capable of answering the thorniest and most complex questions while giving the questioner the sense that his answers were eminently trustworthy.

The masses who flocked to visit him and benefit from his wisdom were shocked to discover that this man, who was thoroughly immersed in Torah and who fought valiantly in every battle to uphold the laws of the Torah, was somehow knowledgeable in every area and was well-acquainted with events in the world. This impression was shared by roshei yeshivos, political askanim, and even physicians and scientists.

On more than one occasion, I watched as the foremost medical professionals set aside their own opinions and accepted those of Rav Halberstam. On a personal level, I also served as a messenger on behalf of many politicians who sought the rov’s counsel. On many occasions, I was astounded by his psychological insight and his deep understanding of the principles of chinuch, and his understanding of politics and public affairs was equally impressive.

Years ago, I noticed an effusive letter of thanks on his table from the late Professor Zev Vilnai. I was duly surprised. Vilnai was an academic who spent his life studying Israel and was the quintessential Zionist. Rav Moshe smiled at my reaction. “He is also a Jew,” he said, “and it is a mitzvah to help him as well.”

So many authors sought Rav Moshe’s approbation for their seforim, while poskim referred difficult shailos to him and yungeleit sought his counsel. In short, every Jew saw him as the address for a wide range of questions. His wisdom was sought by everyone – bnei Torah and ordinary laborers, Sefardim and Mizrachniks, the Litvishe and even the secular. All of these people visited him in his home on Rechov Yoel or at his bais horaah on Rechov Yehoshua (and before that on Rechov Yeshayahu) and were enchanted by the man they met.

Rav Moshe was a multifaceted individual and a formidable leader.

He was my rebbi for many years. I sought his guidance partly as an askan, but mainly as a family man, and my family and I followed his teachings meticulously. I visited his home countless times. We lived by his advice and we thrived on his tefillos. On more than one occasion, he saved us from potentially disastrous missteps. He resolved our most complex dilemmas and helped us through our most distressing hardships. He was our personal source of support and guidance. When he passed away, we felt – as did many others – that we had been forsaken. We understood more than ever what it meant to be shattered by a loss.

This week, a story about Rav Moshe appeared in one of the weekly parshah sheets distributed in shuls. The story was attributed to Rav Matisyahu Deutsch, the rov of the Ramat Shlomo neighborhood of Yerushalayim and son-in-law of Rav Moshe. Rav Deutsch related that Rav Moshe once took his children on a trip to daven at the burial sites of various tzaddikim. On the way from Kever Rochel to Chevron, he told the driver to stop at the side of the road. Pointing to a nearby mountain, he told his children, “This is where the se’ir la’azazel was thrown off a cliff on Yom Kippur to atone for the Jewish people’s sins. You certainly remember,” Rav Moshe added, “that the person who took the se’ir la’azazel to its death always died within the year, yet the Gemara relates that there was a long list of distinguished people who coveted this task. How is that possible, if they knew that they would perish within the year? The answer is that they wanted to be the instruments of kapparah for the Jewish people,” he explained. With that, he burst into tears and said, “Remember this well: A Jewish person must be prepared to sacrifice his body and his soul in order to benefit others!”

• • • • •

I had an even closer connection with Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro zt”l. I grew up in a small community where there were few families of bnei Torah, and it was only natural that the few families who lived there were closely connected to each other. My father, Rav Moshe Menachem Yaakovson zt”l, was the rov of the community for 50 years, until he passed the position on to his eldest son, who still occupies the rabbonus today. We grew up with a close connection to a yeshiva where two distinguished families resided: the family of the famed mashgiach Rav Shlomo Wolbe zt”l and that of the rosh yeshiva, Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro zt”l.

Yeshivas Be’er Yaakov was founded at the same time as the State of Israel itself. The yeshiva’s history is deserving of an entire article in its own right. It was first founded by Rav Wolbe as a yeshiva of the Ezra movement, but when the leaders of the movement saw that the yeshiva was taking on a chareidi character, they chose to dissociate from it and left Rav Wolbe alone. Uncertain if he could sustain the yeshiva on his own, Rav Wolbe sought the advice of the Chazon Ish, who encouraged him to continue. It was the Chazon Ish who suggested tapping Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro to serve as the rosh yeshiva. Rav Shapiro was one of the most prominent talmidim of the Brisker Rov and had a close relationship with the Chazon Ish as well. In fact, Rav Moshe Shmuel was the last person to visit the Chazon Ish’s home before his passing. Rav Wolbe also recruited my father, who was a yungerman in Yerushalayim at the time, to serve as a maggid shiur in the yeshiva. At his behest, my parents settled in Be’er Yaakov, which was a spiritual wasteland at the time, and lived in the yeshiva along with its talmidim.

In addition to serving as the rosh yeshiva, Rav Shapiro also functioned as the rov of Be’er Yaakov. Ultimately, he offered the position to my father. I once asked him why he had done that and he explained, “I discovered that being a rov in a place like Be’er Yaakov means being not only a rov, but also a social worker and a psychologist, and it also means raising money for the upkeep of the mikvah and the slaughterhouse. I saw that it wasn’t for me, but I also saw that your father was very much suited to the job.” For several years, my father served concurrently as a maggid shiur in the yeshiva and as the rov of the community, until he found it too difficult to fill both roles and chose to dedicate himself to the position of rov. Sometime later, he opened a seminary for Sefardic girls. That school went on to be instrumental in creating thousands of Torah homes.

Thus, Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro was like an uncle to us, a relationship that we enjoyed with Rav Wolbe as well. As a child, I grew up in his presence, and I knew that I could approach him to discuss any issue or question. As an adult, I took advantage of that relationship as much as I could. I saw that people came to him from all over the country to ask questions, to seek his advice, or simply to receive brachos. At times, people would move heaven and earth in order to be admitted to his presence. Why, then, I reasoned, shouldn’t I capitalize on my own connection with him? In essence, I had constant access to his home. There wasn’t a single time when I wanted to see him and was prevented from doing so, even when he was lying in bed in his own room.

When we were children, we spent our days in a courtyard from which we could see Rav Moshe Shmuel in his study in the yeshiva. Through his window, we saw that he was always immersed in learning. He sat in the same position, almost invariably with his hand on his forehead. In essence, we witnessed the births of his famous seforim, Kuntres Habiurim and Shaarei Shemuos. When we grew older, we became talmidim in his yeshiva as well. For my benefit, since I didn’t speak Yiddish, Rav Moshe Shmuel delivered his daily shiur half in Hebrew. One could say that he was fond of me. In later years, various politicians would take advantage of my relationship with him in order to gain access to him and to explain their positions.

I have written about Rav Moshe Shmuel often over the past ten years. His file in my personal archives is overflowing with pages. In addition to the many photographs I took over the years, there are countless stories, some of which are not even known to the public. I have written much about his remarkable conduct bein adam lachaveiro and about the wondrous occurrences that were commonplace in his home. I wrote about his intellectual genius and about his phenomenal musical talent, which was reminiscent of that of his illustrious rebbi, Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz zt”l.

One of Rav Moshe Shmuel’s famous written pieces deals with the Gemara’s account (Yevamos 62) of the deaths of the talmidim of Rebbi Akiva, who perished because they failed to treat each other with respect. On an incidental note, Rav Moshe Shmuel questions why the Gemara describes the talmidim as “12,000 pairs,” rather than simply as 24,000 talmidim. The main thrust of the essay, though, is a discussion regarding the concept of kavod habriyos, which Chazal describe as being so important that it overrides a negative commandment in the Torah. Rav Moshe Shmuel points out that a mitzvas lo saaseh, a negative commandment, is so stringent that the Torah requires a person to sacrifice all his worldly assets in order to avoid transgressing such a commandment (a requirement that does not apply to a mitzvas aseh). Nevertheless, he notes, Chazal state that kavod habriyos is an even greater imperative. He adds that the Vilna Gaon comments that the majority of the Torah – or, according to one version of the quote, the entire Torah – is intended to bring joy to human beings, noting that this is an “awesome chiddush.”

In the same essay, Rav Moshe Shmuel goes on to outline the standards of kavod habriyos and respect for peers that he expects of the talmidim of his yeshiva. Then he adds, “In a yeshiva, the love between talmidim must be particularly pronounced. I once had the privilege of seeing our master, Rav Boruch Ber zt”l, when he visited our city of Bialystok, and he asked his son-in-law, Rav Reuven Grozovsky, to identify which talmidim in his yeshiva in Kaminetz were from Bialystok. Then, before Rav Reuven could even respond, Rav Boruch Ber himself remembered and exclaimed aloud, ‘Oh, Chaim’ke! Chaim’ke is learning by us!’ This is how Rav Boruch Ber spoke. Now, I knew Chaim’ke very well. He was far from being an outstanding talmid. In fact, he was far from being even a mediocre talmid. Yet, Rav Boruch Ber pronounced his name with such great love and fondness. From this incident, we can see the level of love that one should have for a ben Torah. That is how the brotherly love in a yeshiva should be. Every person should be viewed in a positive light.” Indeed, Rav Moshe Shmuel himself excelled at viewing others favorably and his interpersonal conduct was stellar in every way.

Ten years ago – in Nissan of 5766 – I was in Be’er Yaakov along with some of his other close associates and we sensed that his strength was ebbing. He was very weak and lay in his special bed in his home, which was like a hospital bed. One of his sons was perpetually at his side. With his vast medical experience, Rav Yecheskel Eschaik, who had been close with Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach zt”l, tended to all of his medical needs. We were all deeply frightened; the mood in Be’er Yaakov was very somber.

The month of Nissan is bein hazemanim, a time when we had Rav Moshe Shmuel entirely to ourselves. During Nissan, the yeshiva was mostly empty of its talmidim, and since the majority of the populace of Be’er Yaakov is chiloni, there were few people seeking Rav Moshe Shmuel’s attention. The greater public was preoccupied with its own concerns, while we – the handful of frum families in Be’er Yaakov – would come to the yeshiva to see to it that the rosh yeshiva had a minyan. Occasionally, the minyan would be held in his home. This was the standard practice both in my youth and in the later years when I spent Pesach in Be’er Yaakov with my family.

That year, bein hazemanim was a very distressing time for us. It was saddening to watch Rav Moshe Shmuel suffer and to know that his health was failing. Rav Moshe Dovid Lefkowitz, the mashgiach of Be’er Yaakov then and now (who serves today alongside the current rosh yeshiva, Rav Yitzchok Dovid Shapiro, the eldest son of Rav Moshe Shmuel) was present for most of the time; Rav Moshe Shmuel was his uncle. “His condition is very bad now,” Rav Moshe Dovid told me, “but when the zeman begins, the rosh yeshiva will have an infusion of vitality.” We waited eagerly for the zeman to begin, but the rosh yeshiva passed away on the first day of Iyar, just before the opening shiur of the summer zeman.

It was a tremendous loss for the Torah world, a loss that defies description. Rav Moshe Shmuel was not only our posek and our greatest source of encouragement. He was also the man who infused us with joy and made us feel truly alive.