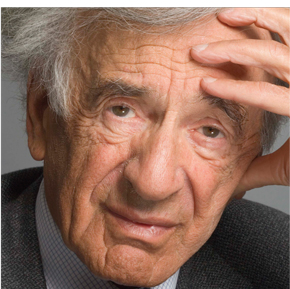

The most famous survivor has passed away. Elie Wiesel, who left this world this past Shabbos, was known as the ultimate witness, the conscience of mankind and a man whose very face mirrored the suffering of the people he never forgot.

Yet, as Torah Jews, and for me writing in a paper that represents daas Torah, we cannot flinch from commenting upon some of his early writings that do not reflect our mesorah. It may seem somewhat churlish to bring this up so soon during the shivah, but the media has already begun to quote some of the more famous phrases. The day after his petirah, the day of the levayah itself, the New York Times cited the searing line in Night: “Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever… Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my G-d and my soul and turned my dreams to dust.”

The Times goes on to quote a series of questions Mr. Wiesel addressed throughout his more than 60 books, concluding with, “How can one go on believing?” and the sad fact that “he rarely offered answers” to these penetrating and often painful queries.

While the Times reports that “he never abandoned faith,” it also recognizes that “central to Mr. Wiesel’s work was “reconciling the concept of a benevolent G-d with the evil of the Holocaust. ‘Usually we say, ‘G-d is right or G-d is just’…he once observed, ‘but how can you say that now, with one million children dead.” All of that was published on the very first day Mr. Wiesel died. We can only imagine what else will be quoted and claimed in his name. And so, with profound sadness, I feel that we must provide the alternatives to these statements, before they become enshrined, once again, as accepted theology and hashkafah.

But first, if I may, a few disclaimers, and a bit of perspective. My father z”l, too, was liberated from Buchenwald on April 11, 1945, and also lost many close relatives. I can totally empathize with a 16-year-old orphan who lived through the gehennom of Auschwitz and took decades to return to the full faith of his ancestors. In fact, Chazal (Bava Basra 16b) teach us that “ain adam nitpas beshaas tzaaro – a person cannot be blamed for what he says when he is in pain.” Surely, few people have ever suffered as horribly as Elie Wiesel and, therefore, this is not about judging or impugning him in any way, G-d forbid.

Furthermore, when I began doing teaching training in many states and several countries for Torah Umesorah, my rebbi, Rav Yitzchok Hutner zt”l, guided me in many ways. Since I had the zechus to translate his classic maamar about teaching Churban Europa (his term of choice), he knew that I was aware of his approach to the subject. However, he added an important caveat. “Remember to speak differently in front of survivors than you do before the younger generation,” he admonished me. “They have sensitivities that must be respected.”

I also heard from others that he gave great kavod to survivors who never questioned their faith, but also refrained from criticizing those who did. He would remind everyone dealing with survivors who had lost their emunah that “al tadin es chavercha ad shetagia limekomo – don’t judge someone until you have stepped into his shoes” (Avos 2:4). I am indeed a child of survivors, but was not there myself, so it would be presumptuous of me to be critical of anything that Mr. Wiesel said or wrote. However, I often shared with Churban Europa teachers that we must establish the correct hashkafah about the Holocaust without denouncing one who actually lived through the torment of those horrific years.

Secondly, it is appropriate this week in particular to commemorate the wonderful things Mr. Wiesel did accomplish for Klal Yisroel. As a true noseh b’ohl im chaveiro, he taught us all what it means not to forget our brethren, be they those who perished or those who were languishing under Soviet oppression. Furthermore, almost singlehandedly, he made the great kiddush Hashem of demonstrating that we Jews are consistent. If we are critical of those who were silent during the massacres of World War II, we must show that we now care about others, and Elie Wiesel led us in protesting the evils of Darfur and Bosnia, Cambodia and Rwanda. In that, he was a shliach for all of us. When necessary, his stature was such that he could criticize presidents, such as when President Ronald Reagan strangely decided to visit the military cemetery in Bitberg, where members of the Nazi S.S. were buried. Lastly, in later years, Mr. Wiesel rekindled his relationship with fellow Buchenwald survivor, Rav Menashe Klein zt”l, author of the Mishneh Halachos, and was instrumental in helping him build Kiryat Ungvar, a truly great mitzvah.

To be fair, let us begin to contrast a totally Torah hashkafah with the sentiments of Night and other early Wiesel works by quoting from another survivor, the Klausenberger Rebbe zt”l. He explained the universal custom to cover our eyes during Krias Shema with the following explanation (see Ohel Moshe, Bamidbar, page 631): When we accept the yoke of heaven upon us during Shema (Brachos 13a), we declare that, despite the fact that with our human eyes we perceive what we think is middas hadin (rigorous justice), as represented by the name Elokim and compassion, as represented by the four-letter name of Hashem, every act of G-d is really rachamim, mercy, often in disguise. For that reason, we close our eyes so that we don’t react with limited human sight to what seems to be, but to a higher vision, that of the all-merciful G-d.”

The Klausenberger Rebbe, too, lost every relative, including his wife and nine children, but would often quote the timeless words of the Chasam Sofer. He explained that when Hashem told Moshe Rabbeinu (Shemos 33:23), “You will see My back but not face,” it meant that at the time tragedy is happening, we cannot begin to fathom its meaning. However, as time passes and we look in hindsight, we begin to understand. To the Rebbe, there was never any question of faith. That was a given. The meaning of something as colossal as what is now called the Holocaust would have to come later.

The Chofetz Chaim famously taught people going through difficult times, “Do not say that it is bad. Say that it is bitter.” Of course, pain hurts, but if we remember and believe that it is ultimately for our benefit, we can often survive a difficult period with our faith and emunah intact.

Rav Yaakov Meir Schechter often quotes (see Venichtav Basefer 2:162) Rav Tzadok Hakohein of Lublin, who says that on the night before Yosef Hatzaddik was elevated from the pit to royalty, he began to have doubts about ever being rescued and started to give up. Finally, he triumphed over his despair and then was saved. Rav Tzadok said that the power of evil always tries to get us to feel that all is hopeless, but we must take strength from Yosef Hatzaddik and be certain that salvation will come.

The Torah understanding of tragedy has been explained by many gedolim through mesholim and parables. Rav Yeruchum Levovitz (see Nefesh Shimshon, Tehillim, page 175) declares that in this world, virtually every gift from Hashem comes with a delay. For instance, the farmer must put a seed in the ground, watch it disintegrate, and then perform many difficult tasks. Even then, he must wait patiently until fruits, vegetables or grains actually appear. For this reason, Seder Zeraim, the section of Mishnah dealing with agriculture, is called emunah, faith (Shabbos 31a), because the farmer must have faith that all of his efforts will come to fruition.

In our lives, too, there are many delays until the blessings arrive. But we must always have emunah that they are coming. As Rav Shimshon Pinzus concludes, explaining the mashgiach’s flaming words, “the seed of Moshiach had to go through the disintegrations of the first and second Botei Mikdosh destructions, the Spanish Inquisition, and the Shoah” until we could blossom and grow.”

Rav Pincus elsewhere (Tiferes Shimshon, Shemos, page 50) shares with us the tremendous chizuk that we should feel if are davening for someone to get well and no improvement seems to be happening: “If we all had the proper emunah, we would realize and truly believe that every word of prayer has had an effect. Sometimes we can see it immediately and at other times its effect is temporarily invisible, but it is always there.”

Of course, the sad occasion of the passing of Elie Wiesel is not the time to attempt to answer all the problems of theodicy and understand tzaddik vera lo and rasha vetov lo. However, as Rav Yeruchum put it succinctly, “How to accept suffering with love is the main source of a person’s success in this world” (Daas Torah, Eikev).

The Alter of Novardok offered a moshol that everyone who has ever learned Torah seriously will instantly understand. When we learn a sugya, a section of Gemara, and then look it up in the Rambam, we sometimes discover that the Rambam does not seem to follow the conclusion of the Gemara. This requires analysis and explanation, and sharp Talmudic heads work hard to “answer the Rambam.” No one would simply answer that the Rambam forgot that sugya or page of Gemara. Neither would any Torah scholar think for a moment that the Rambam was simply mistaken. The brilliant scholars of the past eight centuries have always been able to find a solution to these problems. Now, why would we think, G-d forbid, for a moment that the Master of the Universe, the Creator Himself, had no plan or allowed something to happen that was beyond His control? It is simply that we don’t understand because, as Hashem said to Iyov, “You were not there at the beginning of the world and you will not be there at the end, and therefore you cannot understand everything.”

Elie Wiesel tried valiantly to understand. But at the age of sixteen, after the trauma of Auschwitz, who can understand anything? So we don’t blame him and we thank him for all the wonderful things he did do. But we must be intellectually honest and have religious integrity in repudiating what has been published and will be read even more assiduously now that he is gone. Being in the place of Truth, he now knows what is right, and I believe he would want us to elevate his neshamah by correcting what things he needed to be mesakein, so that his neshamah can have the aliyah he so richly deserved.