Eruvin 98: Handle with Care

Finding a permitted way to send mezuzos is important in a community with no sofrim of its own. One sofer wondered if he could send mezuzos to people living in far-flung communities around the world by mail. He knew that the Imrei Yosher permitted sending a Sefer Torah by mail if it is placed in a crate or the like. Although on Eruvin 98 we find that one may not throw kisvei hakodesh, the Imrei Yosher explains that if one sends it in a box marked “fragile,” the postal service can be trusted to be careful with it.

This sofer, however, needed to send mezuzos to a place where marking something “fragile” does not guarantee results. There, the postal service was known to certainly throw the packages around, even if it was in a fairly gentle manner.

When this question was presented to Rav Yosef Shalom Eliyashiv zt”l, he was lenient in this case. “If the recipient requires a mezuzah and there is no other way to send it, it is reasonable to say that this is permitted. After all, that is how people send even important packages to such places, so presumably this is not considered a disgrace” (Imrei Yosher, Part II: 171; Chashukei Chemed, Eruvin p. 665-666).

Eruvin 99: Interruption at a Simcha

On thisdaf, we find a discussion about a pit in a public domain.

In one of the catering halls in a city with a large Jewish population, a very fine time was being had by all until an unpleasant interruption occurred. The children were running around and one child ran right into an expensive glass door, shattering it into smithereens.

The child was injured by some of the glass shards and needed to go to the emergency room.

The next day, the father of the child, who was also the baal simcha and had paid in full before the event, went back to the hall to speak to the owner. To his surprise, the owner began berating him and demanded that he pay for the door.

“What do you mean? I am certainly not required to pay,” said the baal simcha. “I actually came here to demand that you pay for my son’s medical bills. Isn’t it clearly irresponsible for you to have a transparent door in such a position? Why, my son surely did not even notice it until he had run into it!”

When they went to Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein for adjudication, he ruled very clearly. “Look, the claim that the owner of the hall has made is clearly incorrect. Even where his claim is true – that the child is responsible for failing to watch where he was going and breaking the glass door – his father is still free of any financial obligation. This is one of the situations that our gedolim used to illustrate an incorrect understanding of halacha. The common man tends to feel that a child’s father should be obligated to pay for any damage caused by his child. He also naturally feels that if one’s pet damages someone, the owner should not have to pay. How can he control a suddenly maddened animal? Halachically, the opposite is true, however. A parent is not obligated for a child’s damages but often must pay if his animal causes damage.

“As far as the father’s claim, if it is true that the door is not noticeable, he is entitled to receive compensation for the child’s medical expenses. An unnoticeable door constitutes a bor bereshus horabim, a pit in the public domain. It is possible that the owner of the hall can blame the man who made the door if it was truly made in a manner that makes it not noticeable and is prone to being broken and causing damage” (Chashukei Chemed, Eruvin, p. 671-672).

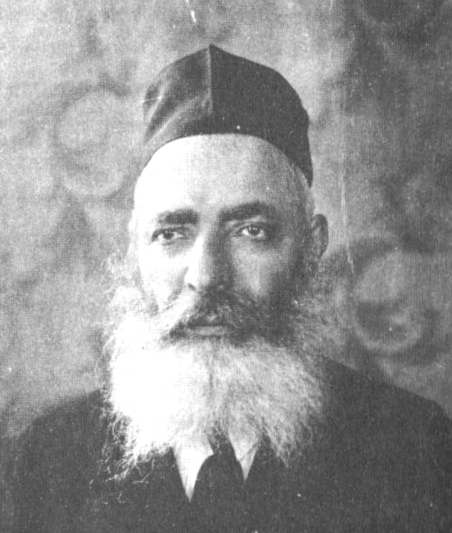

Eruvin 100: The Blueprint of Creation

Rav Yeruchem Levovitz zt”l, the famous mashgiach of Mir, taught one of his characteristically deep lessons to help us empathize with the pain of our fellow Jews. “This world of action is a reflection of higher worlds. Each of the four main worlds has its own unique method to internalize things. Although what we see here is really an outgrowth of higher spiritual realities, they are revealed in our material world in a material form.

“This explains why when Moshe Rabbeinu wanted to feel the pain of his suffering brothers, he went out to see their tribulations. ‘Vayeitzei Moshe vaya’ar besivlosam – And Moshe went out and saw their suffering.’As Rashi there explains, ‘He put his eyes and his heart to feel pained due to their plight.’ Moshe had no other way to truly feel their pain. In this physical world, one must venture out and see it in the flesh. Nothing else will truly evoke enough empathy.

“This explains a puzzling statement of our sages on Eruvin 100. There we find that if Hashem had not given the Torah, we would have learned the prohibition to steal from ants; we would have learned tznius,modesty, from cats.

“Since the Torah is the blueprint of creation, as our sages say, every creature is formed as an imprint of the Torah and can teach proper comportment to one who is attuned to learning from them in the proper way” (Daas Torah, Devorim part II, p. 222).

Eruvin 101: The Limud Zechus of the Chazon Ish

On thisdaf,we find that if the gates of Yerushalayim had not been locked at night, it would have been considered a reshus horabim de’Oraisa.

There is an intriguing leniency that the Chazon Ish makes regarding hilchos eruvin, despite the fact that, lemaaseh,he did not rely on eruvin and nor do his close talmidim. He posits that, nowadays, it is very hard for one to transgress carrying de’Oraisa even in a city that is considered a reshus horabim de’Oraisa. Since every street has many houses, stores and buildings, and is interconnected with other streets on all sides, a person in a city – or in many towns – is always surrounded by four walls. Mide’oraisa,three buildings constitute a wall despite large gaps due to the principle of “omeid merubah al haporutz.” If there is more of the wall standing than not, the entire area is considered to be standing. This is similar to a wall that has some gaps. The entire area is considered a wall al pi halacha if most of the wall is standing. According to Torah law, omeid merubah nullifies any public domain. It is only miderabonon that one needs an eruv in such places.

Although, in general, we maintain that if there is a gap of more than ten amos, this disqualifies the use of omeid merubah, that is only rabbinic. Mide’Oraisa,this is not a problem. It follows that in most cities today, people do not violate a Torah prohibition against carrying even if there is no eruv and vast numbers of people pass through every day. As long as one can invoke the principle of omeid merubah al haporutz, there is no problem min haTorah.

Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l disagreed, however. “The custom of the Jewish people follows the Mishnah Berurah in this matter. He does not even mention this consideration, although it was surely relevant during his time. We must conclude that he did not agree with this leniency” (Chazon Ish, Orach Chaim, p. 304; Igros Moshe, Orach Chaim, Part V: 28:3).

Eruvin 102: A Knotty Question

On thisdaf,we find the example of a knot that is problematic on Shabbos. Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein asked his father-in-law, Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv zt”l, a question regarding tightening a knot on Shabbos: “Can someone tighten the last knot of histzitzis on Shabbos?”

Rav Elyashiv forbade this. “Although the uppermost knot is what determines the kashrus of the tzitzis and not the lower knots, I still do not see any way to permit this. A person tightens this knot because he wishes for it to be tight to ensure that the thirteen windings above this knot do not come loose.”

Rav Meir Diner asked Rav Aharon Leib Shteinman a related question: “If one tightened the last knot of his tzitizis on Shabbos, are his tzitzis kosher?”

Rav Shteinman replied that, bedieved,they are kosher. “Since the first knot was tied before Shabbos, the tzitzis are kosher. Even if we say that the knot that was tied on Shabbos is posul, the tzitzis are surely kosher, since mide’Oraisa the tzitzis are kosher even if one only tied one double knot with a few windings and then closed them with a second double knot” (Chashukei Chemed, p.687-688).

Eruvin 103: The Full Observance of Shabbos

The Ma’aseh Rokeiach explains a famous Yerushalmi in an astounding manner: “The Zohar reveals that Moshiach is called an oni riding on a chamor to teach a very deep lesson. The word oni is an acronym for Eruvin, Niddah and Yevamos. This teaches us that we will rectify the chomer, material, of this world with Moshiach only when people learn these three difficult masechtos.

“There are ten chapters in Maseches Eiruvin. When we add the numerical values of the last letters of the first word of each chapter, we get 615. There is a deep reason for this.

“In both the Zohar and the Yerushalmi, we find that keeping Shabbos is equivalent to safeguarding the entire Torah. Clearly, this is only true regarding someone who keeps Shabbos kehilchasah, adhering to all thirty-nine melachos and all rabbinic decrees. As is well known, Tosafos at the beginning of Maseches Shabbos and other places calls hotza’ah, carrying in a forbidden manner, a melachah goru’a, an inferior melachah. It is only if one also keeps even meleches hotza’ah with all of its rabbinic ordinances – outlined in this masechta – that one’s Shabbos is considered as though he kept the entire Torah. The word eruv has a numerical value of 576. If we add thirty-nine to this to allude to the thirty-nine melachos, we have exactly 615. Add one for the word itself and one gets “haTorah.” This alludes to what we have been saying: One who keeps the laws of eruvin along with refraining from the thirty-nine melachos is like one who keeps the Torah” (Ma’aseh Rokeiach, Maseches Eiruvin; see there for why the initial letters of the first word equal 230).

Eruvin 104: Fighting the Fantasy

The Divrei Shmuel learns an important lesson from a statement of our sages. “In Eruvin 104, we find a dispute regarding how a rodent that imparts impurity should be removed if is found in the Bais Hamikdosh. Should it be removed immediately, even with one’s hands, so as to remove the impurity right away? Or should they wait to bring a vessel so that it will not convey impurity to the one who removes it? The same can be said regarding avodas Hashem. If one has a negative thought, he must quickly remove it. That way, he will be guarded both from leaving defilement and also from promulgating the impurity which starts as a negative thought.”

Rav Shlomo Wolbe points out the essential nature of fighting negative machshavos in avodah. “Literally, at every moment, there is a war going on between one’s seichel,intellect, and his dimyon,imagination. In the words of Rav Yisroel Salanter in Iggeres Hamussar:‘One’s dimyon leads him to the wayward paths of his heart’s negative desires. Woe to us from dimyon, the evil enemy!’ Do not underestimate the importance of working on your imagination. Fighting dimyonos is the foundation of all avodah.

“In yeshiva, you feel this struggle while you sit in front of your Gemara and while you daven. When you go home, be’ezras Hashem, you will see how powerful the dimyon becomes. It will push you to be a ‘chevraman,’to take incessant trips, to read the news and to do many other things that you may prefer to avoid or limit” (Divrei Shmuel, Parshas Vayeishev,p. 75; Iggros Ukesuvim, Part II, #278).