“Did you know Rabbi Greenwald?” I was repeatedly asked while interviewing over a dozen askonim and friends of Ronnie, who was niftar suddenly last week, in preparation for this article.

Of course I knew Rabbi Greenwald, known to all as Ronnie.

Who didn’t know Ronnie? He was a beloved longtime Monsey resident with a zest for life and an infectious laugh. His devoted wife, Miriam, is a renowned author and playwright.

Ronnie was the address for anyone in any sort of trouble.

Whether dealing with young adults in physical or emotional distress, complicated financial issues, tangled legal matters, or any other crisis, Ronnie never lost his cool.

He was the driving force and visionary behind the Monsey Academy for Girls, Areivim, and Otsar, a school founded by my good friend Mrs. Rivka Resnik to rescue girls on the fringe and help them believe in themselves. In that capacity, I had several conversations with Rabbi Greenwald, who had the uncanny ability to get to the heart of the matter, to dissect delicate issues with sensitivity and discretion.

Rabbi Shmuel Gluck of Areivim, a noted author himself, perhaps summed it up best. “I have never met a more confident man without a shred of arrogance.

Ronnie knew his limits yet reached beyond. He understood exactly what he was capable of, yet thought nothing of himself. He made everyone feel like he had all the time in the world and had an endless capacity to absorb their pain.

“He had the ability to connect with everyone, and at the same time, create proper boundaries,” stressed Rabbi Gluck. “He maintained his self-respect even in the most challenging situations.”

Ronnie served as Chairman of the Board of Areivim and would show up to nearly every meeting. “He put forth brilliant ideas with such simplicity, and mediated tricky situations by putting you off guard. He would just schmooze, do a lot of listening, throw in an idea or two, and soon everyone was on the same page.”

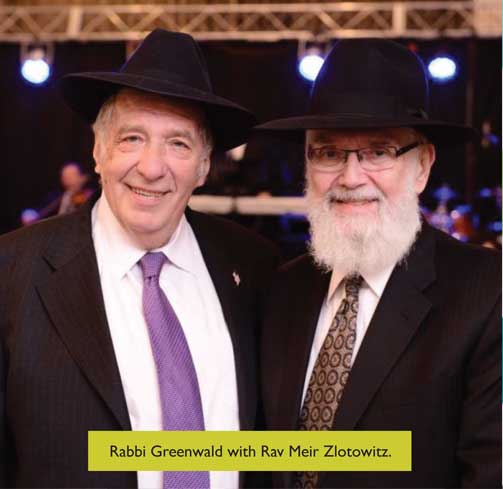

Rabbi Meyer Zlotowitz, of Artscroll/Mesorah publications, described Ronnie’s strength as the “unique ability to make everyone he knew feel like they were the closest person to him. He loved people and would do anything for them, even when their problems were self-made, even if he owed them nothing or they wouldn’t step up to the plate in return.”

On one occasion, a person who had been unwilling to get involved in a situation where Ronnie needed help asked to speak with him a few weeks later. His daughter wanted to go to camp, and he needed Ronnie’s “pull” to get into Sternberg. “Why are you helping him when he didn’t help you?” Ronnie was asked. “What do you mean?” he replied with a smile. “She’s a great kid. What has this got to do with her?”

Rabbi Zlotowitz recalled meeting Ronnie at a chasunah where an adult with Down Syndrome was dancing in the center, perspiring heavily. “Ronnie came over to the young man, gave him a big hug, patted his sweaty face, and danced with him in the center. You’ve got to really love people to do that.”

One of the young girls whom Ronnie counseled showed up at a meeting wearing outlandish, ridiculous earrings, clearly begging for attention. Ronnie spoke with her but didn’t say a word about her fashion accessory. Soon the girl couldn’t stand it and asked, “Aren’t you going to say anything about my earrings?” Ronnie just shrugged and flatly stated, “If you want to look like a clown, it’s your problem.”

The next day the girl was normally attired.

The fact that so many teens at risk confided in Ronnie, trusted him and revered him, spoke volumes about who he was. He gave them hours of his time, yet with the utmost propriety and distance. It’s rare to find someone so heavily involved in askonus yet so respected across the board.

He didn’t just have time for the big guns, for the cloak and dagger missions and spy adventures that would make a fascinating piece of fiction but were all true. He also found the time to meet with distraught parents whose children were going through gehenom, to reassure them that he believed in their teens and knew they would return.

Ronnie’s day was only 24 hours long, but he had time for everyone. “That’s the making of a gadol,” said Rabbi Zlotowitz. “A gadol is someone who always has time.”

Rabbi Leibish Landesman, a noted dayan who was Ronnie’s neighbor for many years, recalled a story that starred his son Avigdor over two decades ago.

“I lived on Elaine Place at the time and davened in Rabbi Schweitzer’s shul next door. Ronnie, who lived on Francis Place, would often come to the minyan. One year, on Simchas Torah, there was a candy man in the shtiebel who doled out candies to the children. Ronnie came to shul a bit late with his young grandson, and all the candies were already taken.

“The little boy was very upset, so Ronnie asked the other children if they were willing to share their stash. None of them volunteered; which normal child wants to give up his sweets? My son Avigdor, who was seven years old at the time, opened his fist and handed several candies to the little Greenwald boy.

“Ronnie thanked him heartily, and asked Avigdor to come to his house after Sukkos. My son didn’t forget the invitation, and knocked on his door a few days later. Ronnie handed him a 100 dollar bill as a sign of hakoras hatov! My son had no idea how much the bill was worth, but he knew it was more than a dollar.”

For many years, Ronnie took a special interest in Avigdor, the boy who had given of himself so selflessly.

“Years later, when Avigdor was learning in Lakewood, Ronnie asked me if I would allow him to travel to Uman. Ronnie was heading to Uman for Rosh Hashanah (this was in the early years, when Ronnie was involved in negotiations with Ukraine to allow Jews to visit Uman) and wanted to take Avigdor along. I gave permission, and Avigdor spent an uplifting Rosh Hashanah davening at the holy site. Although Ronnie had given him a hundred dollar bill years earlier, he still felt he owed my son for that long-ago act of kindness.”

Rabbi Avigdor Landesman, today a mentor for at-risk youth who lives in Eretz Yisroel, recalled Ronnie’s fatherly relationship with the children on the block. “He would ask us a complicated question on the parshah every week and would wait for us to come up with the correct answer. Every child who answered the question got a few dollars or some other prize.”

Rabbi Landesman recalled Ronnie’s determination to help anyone who needed him, regardless of whatever else was on his plate. “He could be traveling to Morocco for pikuach nefesh, but if a child was disinvited from a yeshiva, Ronnie would move heaven and earth to get him back. It didn’t matter how busy he was or how many politicians were waiting to talk to him. To him, every request was equally important.”

A couple of years ago, Rabbi Landsman’s young daughter wanted to get into a specific program in Eretz Yisroel. Against her father’s objections, she called Rabbi Greenwald to ask for his assistance. A few minutes later, after several long-distance phone calls, the matter was arranged.

“He had an enormous power to do things for the government on behalf of Klal Yisroel,” stressed Rabbi Avrohom Biderman, chairman of Shuvu International. “He was very close to former Congressman Ben Gilman, who was a great oheiv Yisroel, and helped him forge other connections in the highest echelons of government.

“A friend of mine was traveling to Eretz Yisroel for Pesach and discovered on Sunday, just a few hours before his flight, that his passport had expired. The only one who could help him was Ronnie Greenwald, who despite having never met before, somehow had the passport renewed.

“He was a ‘can do’ kind of guy. The word ‘can’t’ didn’t exist in his vocabulary. There are so many secret missions he was involved in, the details of which cannot be revealed even today. I once got a call from him and the connection was bad. ‘Where are you?’ I asked. ‘Kazakstan,’ he replied calmly. I have no idea what he was doing there, but I knew it was a matter of pikuach nefesh. After all, you don’t go to such places on vacation.”

“I knew Rabbi Greenwald since we started Otsar,” said Mrs. Rivka Resnik, guidance counselor and beloved adoptive mother to many teenagers at risk. “I met with him several times, and he spent hours helping my students. No matter how busy he was, he always took my calls or called me back right away.

“The interesting thing about him was that he seemed like a mellow, chilled zeidy, not like a public figure. He related to the girls; he would always tell them how much he believed in them and that everything would be okay. Coming from Ronnie, it was such a nechomah for the parents to hear this.

“He had a great sense of humor and an ayin tovah. I remember that at one meeting, he told us he was coming from Evergreen Supermarket, where he’d just walked up and down the aisles, marveling at how our community has grown. He had a sense of wonderment and awe,” Rivka recalled.

“Rabbi Greenwald was my neighbor on Regina Road for the past fourteen years,” said Rabbi Avi Lehrer, a social worker for Areivim. “He wasn’t just a neighbor, more like a close friend and zeidy to my children. Several years ago, before I joined Areivim, I was a rebbi of teenage boys and had fourteen class clowns in my classroom.

“I was at my wit’s end, and confided in Ronnie about my troubles. He offered to come to my classroom and talk to the boys. I was desperate enough to take him up on the offer. Incredibly, Ronnie showed up and talked to my students for two hours! They couldn’t get enough of the ‘cool rabbi’ and kept asking me when he’d come again.”

This was the Ronnie everyone knew and loved, the man who found hours of “spare” time to meet with troubled teens, headed Mishkan at Camp Sternberg, was on the board of nearly every major institution for children at risk, brokered high-level deals on behalf of the American government, and negotiated for the release of prominent refuseniks and political prisoners.

Rabbi Zvi Gluck of Amudim, who deals with crisis intervention, worked hand in hand with Ronnie for many years. Son of the renowned askan Rabbi Edgar Gluck, Zvi deals with Jews arrested in foreign countries or who have run-ins with the law.

“Ronnie always did what was right regardless of what other people thought,” said Zvi. “He would wear an American flag on his lapel because he thought it was important to show hakoras hatov to our medinah shel chesed. He was a ‘black hatter’ without a ‘black hat’ attitude.

“My wife, Aviva, repeated something he would often say. ‘There’s no such thing as off the derech. The derech just isn’t wide enough.’ He was a visionary, saying these comments well before they were politically correct.

“Ronnie was a champion for children who were abused, slowly and painstakingly building them up again, making them feel that they were worthwhile. He worked hard to bring this issue to the forefront of Klal Yisroel, warning us that we couldn’t push it under the rug and make believe it didn’t exist. He believed in accountability, not in whitewashing the issue and looking the other way. Public opinion meant little to him when he stood up for the rights of our most vulnerable members.”

Rabbi Gluck would spend time with Ronnie in Camp Sternberg, and would marvel at how he met the parents each visiting day, among them many former campers. “He was the director of Sternberg for fifty-one years, and he remembered every single face of a former camper. Maybe he didn’t recall their married name, but when they mentioned their maiden names his eyes would light up. He had a connection with every camper, and there were tens of thousands over the years, who passed through Sternberg.”

Rabbi Benzion Klatzko, founder of Shabbat.com, who hosts over a hundred guests for Shabbos each week, had a close relationship with Ronnie. “I remember spending a Shabbos in Sternberg,” said Rabbi Klatzko. “There were about 1200 girls in the camp, with about 300 girls in every dining room. Ronnie would go to each of these buildings to spend time with the girls. It was incredible to see the awe and respect they had for him, how comfortable they felt speaking to him and sharing their challenges.

“He felt very strongly that the community was behind the curve with the numbers of children going off the derech. Ronnie would often say that you can’t really reason with a teenager of 15. All you have to do is show them love, and eventually they’ll come to their senses.”

“Rabbi Greenwald was a doer,” recalled his friend Dr. Joel Rosenshein, founder of P’tach. “He understood everything there was to understand about getting things done. If the door was closed in his face he’d go through the window. There was always another way.”

Dr. Rosenshein recalled how Ronnie went to bat over the fate of a young disabled boy, the son of Rabbi Asher Zrihen of Mexico City. Rabbi Zrihen’s severely handicapped son was trapped in Mexico, where it was challenging to care for him properly. Ronnie arranged for Rabbi Zrihen to become the part-time rov of a congregation in Boro Park, enabling him to bring his son to Brooklyn. This young man is today in his forties, and still lives in the Mishkan adult housing.

The stories of Ronnie’s askonus are as unbelievable as they are true. Several months ago, in an interview in Z’man Magazine, Ronnie spoke about some of his exploits over the past forty years, agreeing to be interviewed so that “people should know what they are capable of accomplishing, if only they make the effort.”

Classic Ronnie.

A Lifetime Of Askonus

Rafael Greenwald was born on January 8, 1934, to Reb Yehoshua Falik and Chana Fraida Greenwald, immigrants from Hungary who had settled on the Lower East Side. Later they relocated to Brownsville, where Ronnie studied in Torah Vodaath before going to the Telshe Yeshiva in Cleveland.

Even as a young child, Ronnie stood out for his keen understanding of human nature and ability to relate to every human being, regardless of age or ability. His refreshing sense of humor and take-charge attitude would serve him well throughout a lifetime in the thankless public eye.

In the early 1950s, Ronnie married his wife, Miriam, a brilliant and talented writer. The young couple settled in Boro Park, where Ronnie was a rebbi in several yeshivos, and was an active member of Torah Umesorah. They enjoyed a beautiful marriage, working together on behalf of Klal Yisroel.

Ronnie’s entry into politics began quite by accident in 1962, when he first lobbied on behalf of Torah Umesorah to promote the day school movement across the United States. Sensing his unique talents, George Klein, a renowned activist, asked Ronnie to become involved in the campaign for the future Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

Ronnie, then a young man of 28 with no political experience, embraced the challenge head-on. He used his charisma and understanding of politics to help Rockefeller appeal to his Jewish brothers. The Republican was voted into office with the majority of the Jewish vote. Rockefeller never forgot the favor and became one of Ronnie’s admirers.

A couple of years later, Rockefeller recommended the young teacher to President Richard Nixon, who was running his 1972 re-election campaign. Surprisingly, Nixon, also a Republican, won 35% of the Jewish vote, a rarity at the time.

Why did he do it?

Ronnie recalled his involvement with his customary pragmatism in an interview. “I thought it was important that the Orthodox vote have a presence in the Republican Party.” It was that simple.

When Nixon won his second term, he offered Ronnie a prominent position in the White House. The young askan promptly turned it down. All he wanted was ready access to government officials in order to continue helping his brothers and sisters. At the time, the Republican Campaign Headquarters were in the executive office building near the White House. Ronnie was just steps away from the Oval Office and leading cabinet members. In addition, his phone number was registered as a White House number, which conferred more authority on his requests.

Ronnie derived no personal satisfaction from this arrangement; he saw this as the yad Hashem giving him an opportunity to help Jews around the world.

During the Watergate scandal, Ronnie was called upon to assist Nixon and tried to persuade various Democratic Jewish members of Congress, including Elizabeth Holtzman, Bella Abzug and Arlen Specter, that impeaching the president would weaken the United States and, by extension, hurt Israel.

Though he was not successful and President Nixon was forced to resign on August 19, 1974, rather than face impeachment, Ronnie earned a presidential letter of thanks. Nixon’s successor, President Gerald Ford, greatly admired Ronnie, who continued working in a part-time position as an advisor for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. (No similar position exists today.)

During the Nixon and Ford Administrations, Ronnie used his political clout to help his brothers, asking for and receiving a federal grant of one million dollars (worth several million today) to open a legal aid office in Brooklyn to help the Jewish community. Although he formally retired from the political scene in 1976 when Democrat Jimmy Carter was elected, that was only the beginning of a lifetime of public service.

Ronnie was involved in so many klal activities, we would need an entire book to describe them all. Throughout his lifetime, Ronnie was the heart and soul behind numerous innovative programs designed to help our community’s most vulnerable members.

Dr. Joel Rosenshein recalled the day Ronnie invited him to become the director of Mishkan, a UJA-Federation government-funded program including group homes and a respite program for Jewish adults with disabilities. Mishkan was founded in 1978 in response to the desperate need for such services. This was in the era when disabled children were routinely hidden from view, as having a child with special needs was a stigma and almost no programs existed to care for these children.

As the Mishkan mission statement explains, “In 1978, The Jewish Board of Guardians and Jewish Family Services merged under the moniker Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, promising reinvigorated service for a City in need.”

A proclamation by Mayor Ed Koch announcing the merger read:

“The citizens of New York City welcome the establishment of the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, a mental health and social service agency created through the merger of two of the city’s oldest and finest service organizations… We expect that this new entity, with its unique combination of skill, faith, and determination, will continue and expand upon the tradition of excellence for which its parent agencies have earned the respect and gratitude of all New Yorkers.”

Dr. Rosenshein, who worked together with Ronnie in Mishkan, recalled the mindset of the sixties and early seventies regarding the handicapped.

“In those years, the concept of catering to the handicapped and meeting their educational needs was alien. This was during the years when people with disabilities were shut into the closet, or locked into mental institutions where the worst abuse took place.

“There was no Hamaspik, no Yeled V’Yalda, nothing of the sort. Even in the secular world there was almost no structure in place for the handicapped, especially in the school system.”

With Ronnie’s encouragement, Dr. Rosenshein founded P’tach in 1975. P’tach, or Parents for Torah for All Children, was a groundbreaking idea to bring specialized classrooms into regular yeshivos. After his retirement from his position with the Board of Education, he was invited by Ronnie to head the newly founded Mishkan. At the time, Mishkan had only forty children, but it soon quadrupled in size.

“Ronnie had big dreams,” Dr. Rosenshein recalled. “He wanted to convert a building in the heart of Brooklyn into housing for the handicapped. He had the tenacity and ability to make it happen.” Today, Mishkan provides assisted living arrangements for hundreds of developmentally disabled adults.

One day, Ronnie called Dr. Rosenshein and shared a brand new vision. “I want to create a summer camp for disabled children where they can enjoy the fresh air and have a good time just like everyone else.” Ronnie envisioned a separate camp, also called Mishkan, in the middle of Sternberg, an oasis of hope and courage for these brave young men and women.

Ronnie, the director of Camp Magen Avrohom and Camp Sternberg since 1965, knew this wasn’t a simple matter. He was prepared for an uphill battle with lots of setbacks. After all, there was no other place in the entire United States where handicapped young adults spent time with so-called “normal” children. He realized he would be under intense pressure from the parents, so he pre-empted them.

“He called a meeting in the middle of the winter with the Sternberg parents to share his dreams,” said Dr. Rosenshein. “This was a big risk for him as he could have lost his clientele.” To their pleasant surprise, the parents were willing to give it a try. The Mishkan bunks were constructed in the middle of the camp, near the dining room, so that not a single Sternberg camper could miss them.”

Originally, Ronnie was afraid that no one would want to care for the Mishkan children, so he hired aides to work with them. Before long, the Mishkan campers stole the hearts of the Sternberg campers, who considered it a privilege to spend time with them. Many lasting friendships were formed and stereotypes were broken.

“Sternberg was a large camp, with over 1,000 campers per season,” recalled Dr. Rosenshein. “Many years later, if one of these campers would give birth to a child with health issues, she was better equipped to raise the child, having been exposed to the children of Mishkan. This was an example of Rabbi Greenwald’s sheer brilliance.”

Ronnie was also the visionary behind the founding of Kesher, a similar integrated camping experience for higher-functioning children with special needs; Camp HASC; and Camp Simcha, which originally began as part of Camp Sternberg before moving to its own camp in Glen Spey.

He was the architect behind Sternberg’s wildly popular pioneering program, where a hardy group of campers would undergo a grueling wilderness challenge, teaching them coping skills and reliance on each other. This was, after all, what Ronnie personified: grit, determination and an ability to get along with anyone, regardless of their background.

Over the years, Ronnie served admirably in various klal positions, including a stint as the national chairman of the National Council for Synagogue Youth, Executive Director of Yeshiva Toras Emes, New York State Police chaplain, vice president of the Orthodox Union, founding chairman of the Board of the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, and chairman of the Board of the Women’s League Community Residences.

Cloak And Dagger Missions

Ronnie hardly projected the image of spymaster, handler of high-stakes international diplomacy, and rescue activist. Yet his passport was filled with visas from third-world countries no sane person would willingly visit, such as Uzbekistan, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Peru. Ronnie endangered his life, time and again, to rescue his brothers and sisters under almost impossible circumstances.

What motivated him to risk his safety, and that of his family, to help brothers he had never met before?

“I was learning with my chavrusa in Telshe,” he recalled in an interview, “and we were studying the halachah that permits the sale of a Sefer Torah for the mitzvah of pidyon shevuyim, freeing captives. I commented to my chavrusa that this is a mitzvah that we Americans never get a chance to do. Little did I know then that I would spend many decades of my life traveling the world in order to fulfill this mitzvah.”

The name Natan (Anatoly) Sharansky is well known throughout the political and Jewish world. Sharansky was a famous refusenik who spent nine years in Soviet prisons for supposedly spying for the American Defense Intelligence Agency. It is well known that Ronnie was one of the primary activists who worked with Representative Benjamin Gilman (R-NY) and East German lawyer Wolfgang Vogel to secure his freedom.

Anatoly Sharansky’s ordeal began when he was denied an exit visa to Israel in 1973. At the time, the Iron Curtain was tightly closed, and millions of Russian Jews were trapped behind its walls.

The Russians claimed he had been given access to information vital to Soviet national security and could never be allowed to leave. After becoming a refusenik, Sharansky evolved into a human rights activist, working as a translator for nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov and spokesperson for the Moscow Helsinki Group. The Russians were quick to take revenge.

On March 15, 1977, Sharansky was arrested on charges of high treason and spying for the American Defense Intelligence Agency. The accusation stipulated that he passed to the West lists of over 1,300 refuseniks. In 1978, he was sentenced to 13 years of forced labor.

His wife, Avital Sharansky, raised a hue and cry, appealing for assistance abroad. Ronnie, who had a close relationship with Wolfgang Vogel, the official international lawyer of the Communist Party, appealed to Vogel to arrange for Sharanky’s release. Vogel, who lived in East Berlin, was then the only intermediary between East Germany and the West.

There were tremendous risks involved for Ronnie, who was putting his life in danger by meeting with Vogel in a communist country. The Stasi, the notorious East German secret police, were liable to arrest him and charge him with espionage. The odds of success were small. What were the chances that Vogel would risk his reputation to rescue a Jew he had never met?

However, Ronnie didn’t make cheshbonos when pikuach nefesh was involved. Against the advice of many seasoned politicians, he traveled to East Germany to meet with Vogel. Once there, he was disappointed to learn that freeing Sharansky would be highly complicated. After all, as Vogel explained, Sharansky had not yet been tried. If he would be freed before his trial, the public would assume that he was arrested in vain, and this would undermine communist ideology.

It took many years of high-level, dangerous meetings and more than 25 trips to East Germany before Ronnie, working with Congressman Benjamin Gilman, successfully arranged for Sharanky’s release. Natan was feed on February 11, 1986, as part of a larger exchange of detainees. He was the first political prisoner released by Mikhail Gorbachev due to intense political pressure from then-president Ronald Reagan.

Sharansky and three low-level Western spies (Czech citizen Jaroslav Javorský and West German citizens Wolf-Georg Frohn and Dietrich Nistroy) were exchanged for Czech spies Karl Koecher and Hana Koecher held in the US, Soviet spy Yevgeni Zemlyakov, Polish spy Marian Zacharski and East German spy Detlef Scharfenorth. The exchange took place on the famous Glienicke Bridge between East and West Berlin.

Ronnie was also instrumental in the release of Vladimir Raiz, a Soviet molecular biologist, who had been denied permission to leave Soviet-controlled Lithuania since 1972. He remained the target of Soviet persecution for 18 long years. Eventually Vladimir’s wife, Carmela, and her older son, Sholom, were allowed to go to the US, with Vladimir and his younger son, Shaul, remaining behind as hostages.

Ronnie tried to negotiate with the Lithuanian government without success. He then turned to one of his business partners in Lithuania who was well-connected with the government. Ronnie offered them an unbeatable deal: to bring the wealthy Reichmann family from Toronto on board as investors in Lithuanian business prospects on the condition that the Raiz family be allowed to emigrate. Eventually, after intense back and forth, Raiz was given permission to leave with his younger son.

During the week of Pesach, the anniversary of our freedom, Ronnie flew to pick up the Raiz family, traveling with Albert Reichmann in Reichmann’s private plane. The full details of the behind-the-scenes negotiation, which included Lithuania becoming a member of NATO, are still top secret today. Carmela Raiz, who published a bestselling book detailing her family’s ordeal, “Blue Star over Red Square,” famously wrote, “I still don’t know how Rabbi Greenwald got us out of there.”

Greenwald was also involved in the transfer of Shabattai Kalmanovich from the USSR to Israel. However, in 1987 Kalmanovitch was arrested in Tel Aviv and charged with being a KGB spy, sentenced to nine years in prison for spying for the Soviet Union. He was released from prison after five years and returned to Russia. On November 2, 2009, Kalamovitch was assassinated in Moscow.

In another memorable Pesach rescue, Ronnie, working alongside Ben Gilman, negotiated the complicated rescue of a 24-year-old Israeli citizen, Miron Markus, who was living in Zimbabwe.

Ronnie was approached by a French businessman and member of the Israeli Knesset, Shmuel Flatto-Sharon, who was heavily involved in releasing Jewish prisoners around the world. Flatto-Sharon asked Ronnie to meet him in Israel to discuss an urgent matter.

Ronnie met the influential businessman in his private mansion in Savyon, a resort city. Flatto-Sharon first asked Ronnie to help negotiate the release of Anatoly Sharanksy in exchange for a US prisoner convinced of treason.

The idea was to influence the US to release a prisoner named Robert Thompson, a former US official in the Air Force in West Berlin, who had been spying for the Soviets under the noses of his superiors. Thompson was arrested in 1963 after the FBI received evidence of his passing secrets to the communists and sentenced to thirty years in prison.

Since Flatto-Sharon admitted that Sharanksy was not important enough to the US to warrant such a swap, he suggested working on Miron Markus instead. Markus was an Israeli citizen living in South Africa who had an appliance business that required him to travel periodically to Zimbabwe (called Rhodesia at the time). Zimbabwe was a battle-fatigued country, and its neighbors were no better.

In 1978, Markus was traveling in a private plane, piloted by his brother-in-law, Jackie Bloch, heading to Rhodesia, when bad weather forced them to land in the middle of a field in Mozambique. They were immediately accosted by officials of Mozambique’s Marxist government and accused of spying for Israel. Tragically, Jackie Bloch was shot and killed on the spot, while Markus was taken prisoner. By the time Flatto-Sharon spoke to Ronnie, Markus had already been held hostage for a year.

“If they don’t want to negotiate about Sharansky, try to negotiate for Markus instead,” said Flatto-Sharon.

Ronnie realized it was a long shot, but this was a matter of pidyon shevuyim. He called Congressman Ben Gilman from the airport, even though it was 5:00 a.m. in America, to discuss the matter. Ben Gilman was so surprised to be awakened on his private line, he asked Ronnie what he had been drinking!

Gilman, a former army aviator who had been recognized for his heroism during World War II, was a close friend of Ronnie, who had facilitated his election by urging the White House to support his campaign. Ronnie also introduced Ben Gilman to local Monsey rabbonim and askonim who enthusiastically backed his bid. Gilman won the election and became a lifelong friend of Ronnie, working together with him on behalf of Klal Yisroel until his retirement in 2003.

Working in utmost secrecy, Rabbi Greenwald, Congressman Gilman and other diplomats negotiated a complex swap that involved four countries: Mozambique, Israel, the US and East Germany. The other players in the prisoner swap were convicted East German spy Robert Thompson and U.S. student Alan van Norman.

The actual release took place on the first night of Pesach. Ronnie asked a shailah from Rav Moshe Feinstein about traveling on Pesach. After hearing all the relevant details, Rav Moshe paskened, “Definitely, you must travel. Travel and be successful.”

Thus, on erev Pesach, as Klal Yisroel prepared to celebrate the yom tov of cheirus, Ronnie prepared to travel to Mozambique, a war-torn, lawless country. He was accompanied by Congressman Ben Gilman, and joined by Mrs. Markus, who flew in from Israel. After spending the first night of Pesach as guests of the Johannesburg community, they continued on to the dangerous border region.

The group, accompanied by a Newsweek photographer (Ronnie had negotiated their silence about the prisoner exchange, offering them access to pictures of the swap), boarded a small plane to Manzini, Swaziland, deep in the African backwoods. Ben Gilman was very anxious, especially as they were taken by jeep on the long, dusty road to the border town of Gaba. In that very spot, two foreign missionaries had been shot dead just two weeks earlier.

Ronnie kept reminding Ben Gilman that their mission had been blessed by Rabbi Feinstein and there was nothing to worry about. They ate matzah at the border, davening that their mission be successful.

Suddenly, a delegation of soldiers arrived, guns outstretched, holding onto a prisoner who was blindfolded and bound. Mrs. Markus began to shout, “That’s my husband!” and collapsed.

Ronnie greeted Markus by telling him it was Z’man Cheiruseinu and he was a free man. Markus smiled, his first smile in nearly two years. Ronnie never forgot that smile.

Over the years, Ronnie negotiated the release of Raul Granados, who was kidnapped by leftist guerillas in November, 1979, while at a soccer game in Guatemala City. Ronnie, working with Ben Gilman, helped coordinate the exchange of Granados in exchange for a four million dollar ransom.

Ronnie also became involved in the saga of political activist Lori Berenson, a woman from New York who was sentenced in 1994 to life imprisonment for treason by a Peruvian military tribunal. She was accused of belonging to a Marxist rebel group and plotting to overthrow the Peruvian regime.

In 2000, with the support of then-President Bill Clinton, Ronnie led a delegation of American negotiators to Peru to press the Peruvian government to free Lori, or at least give her a fair trial. Thanks to his intervention, Lori was given another trial, convicted again and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment.

Ronnie was also involved in many high-level attempts to ask for clemency for Jonathan Pollard. At one point he tried to negotiate a three way trade involving Israel, the US and Russia. Ronnie tried to arrange for Israel to release Professor Marcus Klingberg or suspected Russian spy Shabattai Kalmanovich to Russia. At the same time, the Russians would release Dmitri Polyakov or Anatoly Filatov, both being held by Russia on suspicion of espionage, and the US would pardon Pollard. Congressman Gilman and Sam Nunn’s former chief of staff, Jeff Smith, were also involved in the complicated details.

Unfortunately, the effort broke down when Yossi Ben Aharon, assistant to Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, insisted on Israel negotiating directly with the Russians. The Israelis were not successful, and Pollard languished in prison until his release this November.

In 1983, Ronnie learned of the plight of Dr. Alfred Zehe, an East German scientist attending a conference in Massachusetts, who was arrested for allegedly handing secret “sonar plan” documents to East German operatives in Mexico. Wolfgang Vogel was put in charge of the effort to free Zehe. He worked with prominent attorney Alan Dershowitz and Ronnie Greenwald.

Ronnie visited Zehe several times and encouraged him to cooperate with authorities for the benefit of his family back home. Zehe pled guilty and conducted a full debriefing in exchange for the promise of a light sentence. Thanks to Ronnie’s involvement, he was released in June 1985.

One of Ronnie’s most prominent endeavors was his efforts on behalf of Sifrei Torah and numerous handwritten kesovim languishing in the basement of a Lithuanian monastery without proper burial. Ronnie learned of these treasures while visiting Lithuania and trying to negotiate for the Raiz family.

Ronnie told the Lithuanian officials that he was a student of Telz and was tasked to search their archives for any remnants of that flourishing community, decimated by the Nazis. They took him to the basement of the monastery, where he saw piles of tattered seforim and the remnants of 300 Sifrei Torah. He opened one of the seforim and was overcome at the inscription, “From the seforim library of Rav Elya Meir Bloch.”

“This is my rabbi!” said Ronnie with emotion. He explained to the officials what a disgrace it was for the Sifrei Torah to be desecrated in this manner, and how important it was to bury them properly. After intense negotiations, the government officials agreed.

Many of the 300 Sifrei Torah were able to be saved and brought to shuls around the world. Ronnie arranged for a large aron to hold the remainder, and purchased a kever close to the ohel of the Vilna Gaon. On the appointed day, Ronnie and a group of askonim traveled to Vilna to bring these precious remnants to kever Yisroel. It was an emotional ceremony attended by many Lithuanian officials whose parents and grandparents may have played a part in the annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry.

During this visit, Ronnie begged the Prime Minister of Lithuania to prevent the desecration of a historic beis olam in Vilna. The government had plans to raze the holy site and build a shopping mall above it. Thanks to Ronnie’s intervention and that of other askonim, the plans were put on hold for many years.

Sunset

After spending most of his adult life dealing with the issues confronting Klal Yisroel head-on, advocating for the disabled, arranging for the release of high-level prisoners across the world, spending hours counseling and listening to teens-at-risk, one would think that Ronnie would slow down in his golden years. But Ronnie didn’t know how to slow down. He continued doing what he did best, helping his brothers and sisters at all hours of the day and night.

Several years ago, he became closely involved with the efforts of Rabbi Zechariah Wallerstein, founder of Ohr Naava and Bnot Chaya Academy, a home away from home for girls at risk. Ronnie would come to visit the girls nearly every week, attending every special event and graduation. The students relished his visits, seeing him as the “cool rabbi” who maintained a respectful distance but understood them so well.

This relationship was forged during Ronnie’s first address to the girls, when he said to them, “Many people live in the world of black and white. When you look at a kid in the world of black and white, if they are good, they are good and if they are bad, they are bad. But not me. I put on rose colored glasses. Therefore, everything I look at isn’t black and white, it is rosy. Everyone else might look at you in black and white but to me you are roses. I see the color in your souls.”

Rabbi Wallerstein stressed, “He was an eved Hashem. Whether taking kids off the street and giving them a new lease on life or working on high-level international negotiations, Ronnie remained a humble servant of his Creator.”

He remained active and involved until his sudden petirah on Wednesday, the tenth of Shevat, January 20, while on vacation in Florida. Ronnie was 82 years young.

The niftar was flown by private jet to New York, and a massive levayah took place at Yeshiva Ohr Somayach in Monsey on Wednesday evening, with a sizeable crowd coming to JFK airport to give him kavod acharon. The aron was taken to Eretz Yisroel, where another large levayah took place at Neve Yerushalayim, followed by kevurah on Har Tamir.

“We shared you from the time we were born,” said his son Rabbi Zecharya Greenwald, founder and principal of Meohr Bais Yaakov. “There were always other people that you were their tatty, their zeidy, you were their older brother. I don’t remember a time when we didn’t have extended siblings. We would go to Eretz Yisroel and come home and find new siblings.”

Rabbi Rafael Greenwald is survived by his devoted eishes chayil Miriam, his children Rabbi Zecharya Greenwald, Rabbi Chananya Greenwald, Bassi Wolf, Rabbi Yisroel Greenwald, Chevy Lapin and Chana Shterna Lewenstein, numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren, as well as dozens of adopted children who called him their father. May his memory be blessed.